KIDAPAWAN CITY (MindaNews / 8 May)—I’ve recently made progress in asserting authentic cultural elements from Kidapawan’s indigenous Obo Monuvu culture in the city’s mainstream consciousness.

“Longguway,” a Monuvu Oggung (narrative song) was performed by Datu Melchor Bayawan and his daughter Sikami during the opening of the Masbad Gallery.

The song is over a hundred years old, and was transmitted to Datu Melchor by the late musical master Datu Manuel Arayam, who himself inherited it from his father Datu Inog Arayam. The song’s words are addressed to a man named Longguway, who is trying to seek a bride, by one of the prospective bride’s parents. The prospective bride, Sovani, is the youngest daughter, and the parents are asking a near impossible price for her: a carabao from Dingilan (a place whose location is now a mystery but which is still remembered by the tribe for the quality of its cattle) with three humps. The significance of the three humps is ambiguous: it could represent three precious objects to be given as gifts (on top of the carabao), or it could simply be an impossibility specified to subtly refuse Longguway’s advances. It has not been transmitted if Longguway ever succeeded in getting Sovani, but a carabao with three humps is still very difficult to find.

A few days after that, the Kidapawan City National High School won the Regional Festival of Talents’ street dancing competition with their dance reenactment of the Rescue of Mayanon and Salomay, a piece of tribal oral history that had been passed down from the late tribal historian Salomay Iyong himself to Boi Era Umpan Colmo Espana.

Before the coming of coloniality three orphaned siblings in Ginatilan were kidnapped to be sold to slavery. While one was retrieved early and the other was never saved, Salomay discovered that one of the three, Mayanon, was in Bansalan, and was now married to another slave and had children. Salomay attempted to smuggle Mayanon and his family back, but incurred the wrath of Mayanon’s slave owner, Datu Ambat, who had Mayanon’s wife Saling put to death. When Salomay returned to Bansalan to continue the rescue, he was captured and tied to a post by Ambat’s men. Datu Ingkal of Kidapawan intervened, sending the Bohani Datu Cone Icdang to retrieve Salomay. Instead of causing bloodshed, Cone sought a peaceful way forward, and with the help of Datu Lambac of Malasila, Salomay’s and Mayanon’s release were negotiated.

I was behind both performances, working closely with Datu Melchor and choreographer Eljay Buzano on them. My hope is that they help bring out the authentic specificity of Kidapawan’s heritage into the mainstream—from the very real difficulty with which its parents let go of their children, to the way historic slavery affects the community. I do not believe heritage is something showcased, it must be lived.

This undertaking is not easy, especially given the predominant attitude of only displaying what is pretty. This attitude is prone to whitewashing and shallowness. But it is most dangerously prone to cultural fabrications.

I have written before how settlers have wantonly imposed their names on Kidapawan’s indigenous places. The cultural pollution does not end there.

Here I list some of the most serious acts of cultural pollution that the Greater Kidapawan Area has had to suffer:

1. The Philippine Trogon is not some Monuvu Ibong Adarna – I do not know who started this piece of cultural fabrication, but MindaNews and several other news outlets have recently published an article that has perpetuated this idea that the Philippine Trogon (Harpactes ardens) is both the basis for the Ibong Adarna and is sacred to the Monuvu. Not only is this ethnographically inaccurate (the bird, sighted at Mt. Apo, holds no such significance for the Monuvu, who call the mountain their ancestral domain), there isn’t even any basis in literary history to even remotely suggest that the Ibong Adarna (a piece of Tagalog text from Luzon) was inspired by a Mindanawon species. The article cites a Tagakaulo, Rene Boy Takyawan, to make an assertion about Monuvu heritage. This seems to be a commonly perpetuated lie, but the bird can change—when we were conducting cultural mapping in Kidapawan the same “Ibong Adarna” association was given to the Apo Myna (Goodfellowia miranda) by one of the writers the Energy Development Corporation hired to give input. The effect of promoting this fake traditional significance is that it displaces actually relevant birds like the Limokon—a sacred omen bird across many cultures—from the mainstream imagination.

2. Reggae is not Monuvu Music – Music festivals and events are often held in Ilomavis, one of Kidapawan’s Monuvu-majority barangays, several times a year and often draw large crowds. Despite the explicitly Monuvu nature of the space, very little actual traditional Monuvu music is played. Instead, Reggae dominates these events, usually Bisaya songs or songs in English sung to a fake Caribbean accent. The effect of this has been for many in the public to assume that Monuvu music sounds like Reggae. This was certainly the feedback I got from some who attended the opening of the Masbad Gallery (“I did not know our music here was so subtle, I thought it was all bassline!”).

3. Baybayin was never used in Kidapawan – I do not know which artists painted those Baybayin designs in Lake Agco, but the effect has been for many in Kidapawan grew up thinking that the Monuvu once used Baybayin. “We should encourage our IPs to return to their native writing,” I recall one naïve teacher in Kidapawan telling me. The education system in particular seems to be guilty of this, with some schools in the Greater Kidapawan Area using Baybayin on their sablays. Underlying this cultural imposition is the insidious assumption that only cultures with writing systems were civilized, and cultures like the Monuvu who do not have a writing system were “savages.” Not only is this patently wrong (the Incan Empire did not have its own writing system but managed to conquer almost an entire continent), it ignores the rich and complex system that guarantees accuracy of information transmission around oral traditions.

4. The Dream Catcher is not a Traditional Kidapawan Craft – Again, a Lake Agco thing. The proliferation of Dream Catchers as souvenir items in a tourist destination within an ancestral domain has created this false impression among the public that it is a traditional craft. Dream Catchers are Anishinaabe, some of North America’s First Peoples, and are foreign introductions to Mindanao. But they’ve become a “native product,” a piece of exotica sold as pieces of commodified culture. Not only has this mis-educated the public, it has cut off a possible market for actual local crafts like blade-making and beadwork.

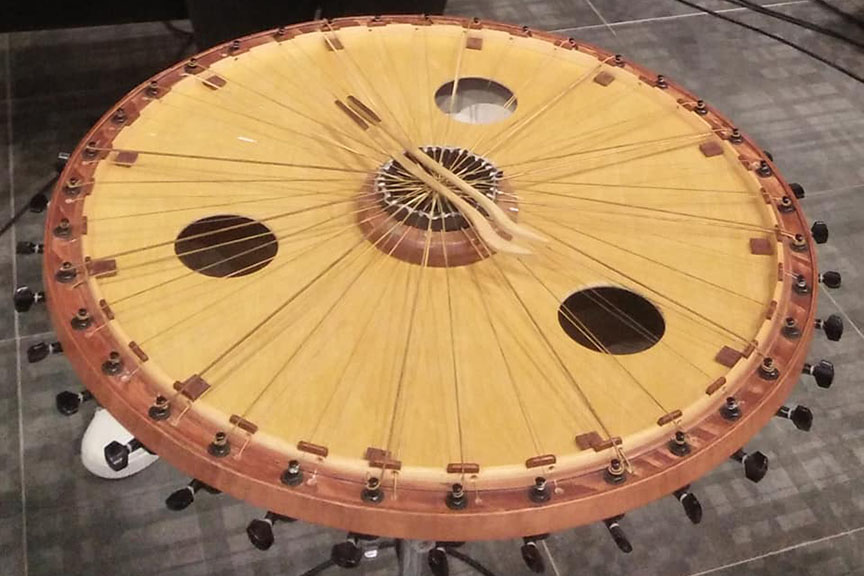

5. The Sinolimbaa is not an instrument – Now this takes us to Arakan, but also the provincial museum, where an instrument made by an American missionary is being displayed as an ethnographic piece. It was given the name “Salimba,” which sounds like the Sinolimbaa (the sky boat in Monuvu epics). But the instrument is not traditional to the Monuvu, and the design is actually inspired by the Kalimba (an instrument from the Shona of Zimbabwe), but the American missionary is lowkey marketing it as an “ancient and traditional instrument,” a branding the museum ends up legitimizing.

6. Timpupo is not a Monuvu word – And this brings us back to downtown Kidapawan, where the Kasadya sa Timpupo Fruit Festival has been celebrated for over two decades. The city government has rightly corrected its official promotional materials some time ago, but some sources still use text that claims the word “timpupo” is a Monuvu word. The festival’s name is from the settler Bisaya language, and not from the indigenous Monuvu tongue. The effect of this over-simplistic and inaccurate etymology is that the public misses on the word’s interesting Monuvu dynamics: although the Bisaya verb “pupo” (harvest) is loaned in Monuvu, “timpupo’s” morphology is Bisaya. “Ting-pupo,” “time of harvest” in Bisaya, would be “timpu to kodpupo” in Monuvu, “timpu” itself a loanword from the Spanish “tiempo.”

Part of the work of a city historian has been to try and clean up these heritage pollutants.

But in a way such fabrications have themselves become part of the town’s heritage, although the area’s public is not yet mature enough to see it that way (the way the Singaporeans owned up to and subverted the artifice of the Merlion).

The work continues to level the public up, so that one day even these fabrications we can honestly celebrate. Because these fabrications too are part of our unique cultural specificity as a community.

(MindaViews is the opinion section of MindaNews. Karlo Antonio G. David has been writing the history of Kidapawan City for the past thirteen years. He has documented seven previously unrecorded civilian massacres, the lives of many local historical figures, and the details of dozens of forgotten historical incidents in Kidapawan. He was invested by the Obo Monuvu of Kidapawan as “Datu Pontivug,” with the Gaa (traditional epithet) of “Piyak nod Pobpohangon nod Kotuwig don od Ukaa” (Hatchling with a large Cockscomb, Already Gifted at Crowing). The Don Carlos Palanca and Nick Joaquin Literary Awardee has seen print in Mindanao, Cebu, Dumaguete, Manila, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Singapore, and Tokyo. His first collection of short stories, “Proclivities: Stories from Kidapawan,” came out in 2022.)

========================================

On this section of Moppiyon Kahi diid Patoy, we remember important dates and incidents that took place in Kidapawan history.

30 April 1979 – Kidapawan’s first Police Advisory Council was convened, composed of civil society representatives.

2 May 1974 – Dominador Apostol, then mayor of Magpet, was ambushed in Kidapawan’s Barangay Mateo. He was killed, along with those in his convoy: Chief of Police Mariano Palmones Jr., and two security personnel, Patrolmen Honteveros Embac and Vivencio Pillo. It is not recorded who is behind the ambush, but the families of the deceased blame the NPA, making this the earliest known terror attack by the communist group.

8 May 1967 – The barrios and sitios of Butsi, Kabunuangan, Salat, part of Arakan, Kisupaan, Sarayan, Naje, Datu Selio, Basak, Roxas, Labo-o, Idauman, Camarahan, Tuael, Magsaysay, New Cebu, Del Carmen, Kamasi, Kisupa-an, Kiyab, Lohong, New Camiguin, and Lebpas were separated from Kidapawan to create the Municipality of President Roxas, by virtue of Republic Act 4869.