(This piece by Ms Aveen Acuna-Gulo was published by MindaNews as a four-part series on June 19, 20, 21 and 22, 2003 to commemorate the 32nd anniversary of the Manili Massacre. It was also published by its newspaper-subscribers. We are re-publishing this in 2018, on the 47th commemoration of the June 19, 1971 massacre.

Like other massacres in the Bangsamoro, relatives of the victims and the survivors continue to await justice, as they await the establishment of a National Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Commission on the Bangsamoro (NTJRCB) which the Aquino administration failed to do. The two-year old Duterte administration has yet to set up the Commission. In early August 2016, then peace implementing chair Irene Santiago said it would be set up “ASAP (as soon as possible).”

In April 2017, Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process Jesus Dureza told MindaNews there was “already a drafted EO for the Commission but you know government, it has to go through the process. It’s not simple as saying the President will sign immediately then it’s done. You have to merge and mesh gears with all agencies of government. Remember in the transitional justice work there are certain quasi-judicial bodies that have to be in place.”

President Rodrigo Duterte has repeatedly vowed to address the historical injustices committed against the Moro people).

*******

32 years after the Manili Massacre

1st of 4 parts: “All I can remember is that the blood was so warm”

By Aveen Acuna-Gulo

MANILI, Carmen, North Cotabato (MindaNews / 19 June 2003) — Manili Barangay Captain Ting Addie Nagli only has the faintest memories of how it all started on that fateful day of June 19, 1971 when both his parents along with more than a hundred others perished in a grenade blast inside the mosque.

“Buotan kaayo to akong Papa (My father was a very good man)”, Ting recalls. “Nakatabang siya sa pagpatukod sa mosque. Tingali mobalor to karon ug P2-3 million kay puros man to hardwood. Dako pud ang among balay pero gisunog pud sa armado. Daghan balay dagko diri sa una (He helped a lot in the building of the mosque which I think would cost P2-3 million today because it was made of pure hardwood. We had a big house but it was burned down by armed men. There were many big houses here before).”

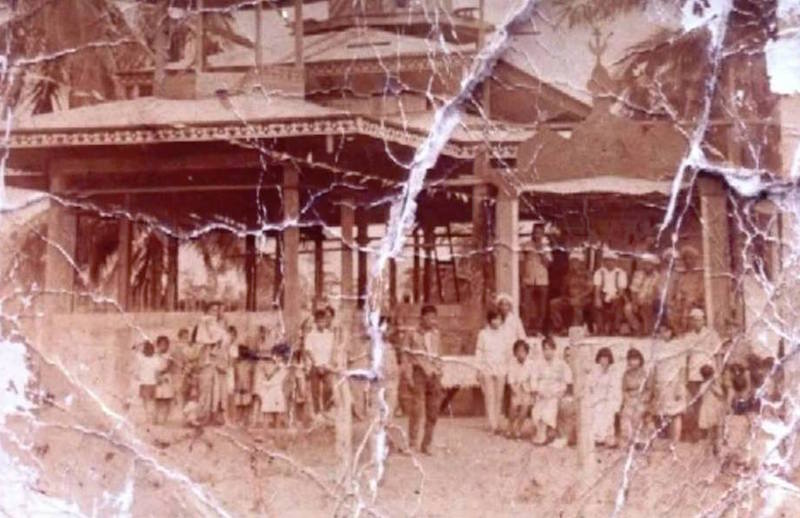

File photo of the mosque in Manili, Carmen, North Cotabato, where the massacre on June 19, 1971 happened. Photo courtesy of IHARYF SUCOL / UN volunteer, 2003

File photo of the mosque in Manili, Carmen, North Cotabato, where the massacre on June 19, 1971 happened. Photo courtesy of IHARYF SUCOL / UN volunteer, 2003

“Ang ako lang mahinumduman init kaayo ang dugo (All I can remember is that the blood was so warm),” the 35 year old softspoken community leader squints his eyes in

recollection. He says the bodies were heaped on his little frame that the armed men did not notice he was still alive.

“The community was called for a meeting inside the mosque at dawn,” recalls Sani Gumaga, another survivor who was about 13 years old at that time. Also speaking in the Cebuano dialect, he recalls how men, women and children braved the rain and biting cold to be able to attend the meeting, called for by what he calls “mga Kristiyano diha sa Aroman” (Christians from Aroman, the immediate neighboring barangay going to the National Highway). He can still recall the name of the PC Captain who called for the meeting.

“Some of the people were evacuees from Kibudtungan who fled here to Masaker because their ears were cut off and their houses burned by the Ilagas,” he continues. “I was here on vacation hoping to earn a little money before school opens.”

Kibudtungan is also another barangay traversed by the National Highway. Masaker’s original name is Bual. This is where the Mosque was located, being near a spring or bual. Muslims build mosques near water sources for the rites of ablution or cleansing before prayers. Residents now want to use again the original name since Masaker evokes

unpeacefulness. Ilaga, which is Cebuano for rat, were the paramilitary forces formed during the Marcos Administration.

“We were not afraid because we were told it was just a meeting. We did not have any hint of anything bad that could come to us. Kinsa may mataranta’g meeting? (Who would be nervous about meetings?)” he chuckles.

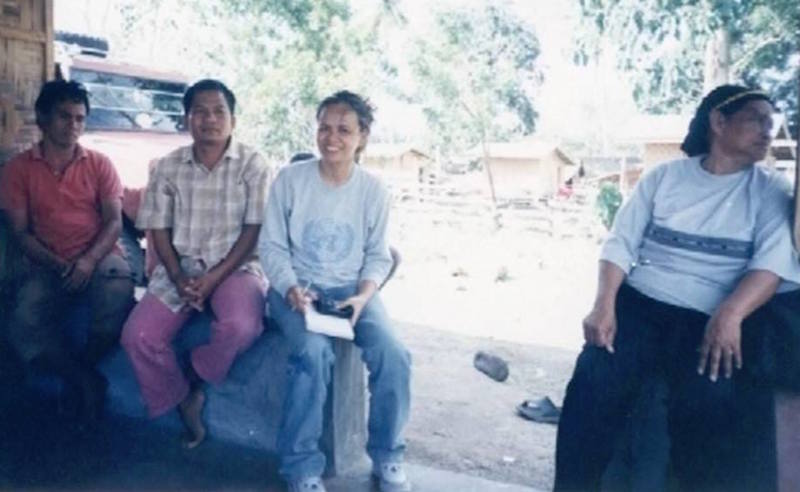

Kapitan Teng Nagli (second from left, beside author) was a little boy when he survived the Manili Massacre in Carmen, North Cotabato. His mother’s body shielded him from the grenade blast. “The blood was so warm.” Babu Lavaia Aliudin is on the right. Photo taken on January 29, 2003 courtesy of GOP-UN Multi Donor Programme

Kapitan Teng Nagli (second from left, beside author) was a little boy when he survived the Manili Massacre in Carmen, North Cotabato. His mother’s body shielded him from the grenade blast. “The blood was so warm.” Babu Lavaia Aliudin is on the right. Photo taken on January 29, 2003 courtesy of GOP-UN Multi Donor Programme

With the people inside, the armed men bolted the men’s entrance but kicked open the women’s entrance. Ting’s father (referring to Barangay Captain Nagli’s father) was told to remain outside. The children were already crying asking for food.

“After two and a half hours, they wanted the men to surrender a machine gun and other firearms. But we did not have any so what could we surrender? Maybe they thought we had guns because every time there was a wedding, we would light firecrackers which we bought in town.”

“The PC Captain insisted that we had firearms; and since he could not get any, he told us to call on our God because we would all be killed. We cried to Allah and our prayers were deafening. Then we heard shots. They shot Ting’s father at close range. Then they threw a hand grenade to the people inside, and I was lifted from the ground this high (gesturing at

least ten inches from the ground). I saw women’s body parts stick to the ceiling of the mosque.”

“I was not wounded because there were still others nearer to the blast so they became my shield. So I ran for my life, zigzagging my way to Muleta (a nearby barangay) because the other armed men blocked my way and there were also others who fled. Some did not make it because they were hit.”

Sani says the survivors inside the mosque recalled that after the blast, the armed men went inside to finish off those they found alive.

“I came back in the afternoon when the armed men were no longer around. I saw all the dead, who just seemed to be sleeping; except that they were lying in a pool of blood this deep (points to above his ankle some six inches from the ground). There was a child with a hack wound on the head; an old man with a dagger still stuck to his right waist”.

“This is where I cried. I’ll never forget what I saw till the day I die. Even up to now when I think about it my heart tightens. Mora’g maka-revenge gihapon ko (It makes me want to take revenge). That’s why I don’t talk about it because I cry. Tama na. (This should be enough).”

Sani’s voice trembles and trails off. He excuses himself as he wipes the tears from his eyes. He picks up his small son from the hood of a rusty vehicle parked nearby. He lights a cigarette.

(Tomorrow: Remains of the Mosque. Aveen Acuna-Gulo writes a weekly column, “The Voice” for Mindanao Cross of Cotabato City and is a UN volunteer deployed in the GOP-UN-MDP3 assisting Peace and Development Communities [PDC] in Mindanao such as Manili).

********

32 years after the Manili Massacre

2nd of 4 parts: Remains of the Mosque

By Aveen Acuna-Gulo

MANILI, Carmen, North Cotabato (MindaNews / 20 June 2003) — There was not a dry eye in the crowd of about thirty that gathered in the porch of the Barangay

Captain’s house. Each one wanted shared a line or two of his or her own story. All of them are survivors of recurrent armed conflict since the Manili massacre in more ways than one.

PDAs (Peace and Development Advocates) Bai Lavaia Aliudin, Zenaida Ranera,

Jamaliya Nagui and Eddie Yap; Bapa Kasim Akmad (Bai Lavaia’s older brother), Kagawad Itu Ampuan and I walk a couple of hundred meters to the mosque or what remained of it: waist-high hollow block walls, charred posts. Big kaymito (star apple) and narra trees stand guard and a portion of the area outside the mosque has recently been made into a burial ground.

“My father and uncles,” Jamaliya points out.

Bapa Kasim shows me the portion inside the mosque where they buried the victims of the massacre: 76 on the spot and more than thirty who died while fleeing. In the months that followed skeletal remains were found within the periphery; these were identified only through their clothes.

“Amo silang gilubong pagka-Domingo (We buried them the next day, June 20),” Bapa Kasim reckons. Bai Lavaia remembers Hadji Ayuddin, Hadji Mutalib and Untua Sultan to be among those also left behind to bury the corpses in the mosque.

Prayers offered at the ruins of the mosque in Barangay Manili, Carmen, North Cotabato where victims of the June 19, 1971 massacre were buried, in the hope that the documentation of what happened would do justice to the memory of the victims and for the peace of heart of the survivors. Photo by JOE BENAVIDES

Prayers offered at the ruins of the mosque in Barangay Manili, Carmen, North Cotabato where victims of the June 19, 1971 massacre were buried, in the hope that the documentation of what happened would do justice to the memory of the victims and for the peace of heart of the survivors. Photo by JOE BENAVIDES

We offer a few moments of silence and proceed to leave because Bapa Itu (Kagawad Ampuan) says he has left his carabao on a loose tether and might get away. We hastily gather young leaves of siling labuyo (native chili pepper) for supper. It was just growing lushly all around.

“Don’t you have plans of declaring this a historical place?” I ask as we walk in the mid-afternoon sun.

“We have already suggested the idea to many of the MNLF (Moro National Liberation Front) who are already in government positions,” says Eddie Yap.

“There are some of us who want a new mosque built above it,” added Bai Lavaia.

All of us were quiet.

The conversation ventured into putting a new structure above the old one will pose chances of erasing the memories that go with the original mosque. We thought it would be good to bring back the pain: it will not make one forget the reason why their people fight for a cause. The lack of pain has put many into the comfort zone, thus forgetting the others who are still crying out for justice. This pain would continue to be a motivating factor for the people to strive to make their community have better lives and should be a very good reminder never to oppress anyone.

Maybe they could fence off the area and put a marker in memory of those who died. Bai Lavaia is a kagawad, maybe she can sponsor a barangay resolution creating it as a historical site.

We recalled a certain battlefield in China, where tourists would wonder, what’s with this grassy stretch of land? Only the guide would tell you that once upon a time, the place had seen one of the bloodiest wars in the history of their country in this place and they let it stay the way it was to remind them never to go to war again.

*****

I take a long drink from an artesian well near a makeshift mosque behind the Barangay Captain’s house. The water is cool and sweet. Built by the DPWH in the early 90s, its depth at 140 feet deep needs an enormous amount of muscle power to generate any amount of water. We hear gunshots.

“The soldiers are shooting chickens,” Bapa Kasim reports.

“We no longer mind it,” Jamaliya offers. “As long as they don’t burn our houses.”

The next morning Barangay Capt Nagli reports that the actual victim was a dog, not chickens. The soldiers then went to Aroman, bought liquor and had a drinking spree.

“Pinanegkaw su ina nu patugial kagina magabi (The mother duck was also stolen around midnight),” Bapa Kasim reported back in the Maguindanao to the Barangay Captain.

“Dunggan gyud namo pagtuok, day (We really heard it when they squeezed the neck)”, added Ed Yap. They didn’t bother to find out who did it.

They could only sigh in silence. Just to keep themselves alive is more important than protesting against armed government soldiers eating dog meat, drinking alcohol and taking what is not rightfully theirs – all forbidden in Islam.

(Tomorrow: Running for dear life. Aveen Acuna-Gulo writes a weekly column, “The Voice” for Mindanao Cross of Cotabato City and is a UN volunteer deployed in the GOP-UN-MDP3 assisting Peace and Development Communities [PDC] in Mindanao such as Manili which she visited in January, before the latest war erupted).

******

32 years after the Manili Massacre

3rd of 4 parts: Running for dear life

By Aveen Acuna-Gulo

MANILI, Carmen, North Cotabato (MindaNews/21 June 2003) –As the interview was being conducted (late January 2003), many had evacuated to nearby barangays and even to Carmen town proper after government troops set up camp, housing themselves in the purok shed in the middle of houses erected by TESDA right after the all-out war of 2000.

The 3 x 4 meter nipa and bamboo structure with a dirt floor housed the soldiers’ radio, chargers and maps. A newspaper page of a semi-nude film starlet is thumb-tacked to a wooden table. A generator provides electricity from 6 in the morning till 11 in the evening. Cell phones are being charged side by side with hand-held radios. A young lady visitor is friendly with us.

“Usahay magdala man na sila ug babaye diri (Sometimes they bring women here),” explains Bai Lavaia, referring to prostitutes, “pero di ta kabalo ug kinsa na siya (but we have no way of knowing who that lady is).

Another squad of troops makes their temporary residence three houses downhill, hearing only faint echoes of the ongoing interview. The bomber, as they call him, sleeps on a makeshift hammock made of parachute material under a big mango tree. More soldiers are distributed in other sitios.

They were told that there were reports of a kidnap for ransom (KFR) gang having passed the area.

“We haven’t seen any,” says Barangay Captain Ting Nagli. “Otherwise, someone would have whispered it to us.” He relates that he was not able to join four other barangay captains in seeking an audience with the Mayor on the report of the KFR gang. He was more concerned with keeping his barangay in one piece while soldiers use it as temporary residence.

“They were polite, though,” he says of the soldiers. “They informed us of their stay when they arrived.

Some say that this is the only security incident in Manili that had no actual firefight in years. But why the evacuation?

According to Bai Lavaia, almost immediately after the troops arrived, they fired six rounds from their cannons. This caused the women and children to cry in terror. The residents packed up and fled to nearby barangays.

“We just advised the residents to consider it an extension of the New Year,” says the Commanding Officer of the Brigade who set up camp in the purok shed. “It’s only a routinary procedure.”

Nagli also relates that a farmer was also made to gather buko (young coconuts) by men in uniform. Accordingly, this farmer could not climb the coconut tree because it was so tall. The uniformed men told him that if he could not gather buko, it would be his head that would be cracked. This scared the man so much he and his family packed up and left. Since the man could not identify the perpetrators, the soldiers said it might have been members of the CAFGU.

Apparently, any military uniform or what soldiers call as “extension of the New Year” has no distinction for residents who have been constantly subjected to encounters between armed groups. Residents also fear retaliation. Most have left, but for the few who still remained, sleds are all ready loaded with everything that they own, ready to move out once fighting erupts.

In the cluster of houses constructed by the Government of the Philippine-United National Multi-Donor Programme 3, (GOPUNMDP3), two Simba vehicles, a 105- and three 80-mm cannons are stationed. Six more 60-mm mortars are stationed in Mulingan, another sitio southeast.

PDA (Peace and Development Advocate) Eddie Yap said the GOP-UNMDP3’s Relief and Rehabilitation component conducted a training for the community in August 2002 on Early Warning and Disaster Preparedness. They were able to put into good use what they had just learned.

“They should not leave this place; they should already come back. We are here to protect them,” the commanding officer of the brigade said.

But the residents felt otherwise. They feared they would be caught in the crossfire.

“It is stated in the International Humanitarian Law that nobody should force the evacuees to return if they still don’t feel safe,” says Irene dela Torre, UN Volunteer for Relief and Rehabilitation.

“We did not leave the place all this time that the other residents fled,” said Bai Lavaia. “We had to be the blocking force.” By blocking force she means that they could act as deterrent to any acts of abuse that can be done by any group in the absence of people.

“I just let my family leave; I’ll just stay here until there will be actual fighting,” says Bapa Kasim, showing his weapons: a slingshot with inch-wide pebbles and a bolo. “In the meantime I’ll just keep watch. I’ve made friends with the soldiers.”

“We have shared to the soldiers what we do as PDAs,” says PDA Zeny Mula Ranera, 4th generation Arab Maguindanaon. “We tell them that we have already experienced war, and that after the peace agreement we have been trained with the help of the UNMDP3 to fight another war the war against poverty and exclusion through peaceful means.”

An assurance was already given by the Armys’ 6th Infantry Division not to involve the Peace and Development Communities identified by the UN-MDP3 in armed engagements. Verbal in nature, the assurance had to be clarified whether troops were allowed to set up camp inside a PDC or how far should they stay from a PDC.

After representations were made by the PDAs and the UNMDP3 to the brigade, the troops pulled out two days after.

(Last part tomorrow: Help comes. Aveen Acuna-Gulo writes a weekly column, “The Voice” for Mindanao Cross of Cotabato City and is a UN volunteer deployed in the GOP-UN-MDP3 assisting Peace and Development Communities [PDC] in Mindanao such as Manili which she visited in January, before the latest war erupted).

******

32 years after the Manili Massacre

Last of 4 parts: Help comes

By Aveen Acuna-Gulo

MANILI, Carmen, North Cotabato (MindaNews/22 June 2003) — For about three decades after the massacre, the people of Manili (100% Maguindanaon)were left on their own to face both man-made and natural calamities. To get back on their feet, the first thing that they do after every armed conflict is to construct a mosque, no matter how flimsy a structure it may be. This shows a deep spirituality and resilience among the struggling residents of Manili.

Manili is only ten minutes by motorcycle east of the national highway but government assistance reached it only recently. In fact, barangay officialssay that it was only in 2002 that two provincial employees reached the eastern boundary of Manili in an ocular inspection of the 7.5 kilometer road traversing their barangay.

The mass exodus after the 1971 massacre was followed by rat and locust infestations, the El Nino, and the “all-out-war” of 2000 that burned their only school building and a third mosque.

“Dalawang sambayang lang tapos binomba naman ng sundalo (We were able to

hold only two prayers here when it was bombed by the military),” says Kagawad Paito Abutasil. Only the walls and the minaret of what was supposed to be a new mosque before it was bombed in 2000, stand, still majestic with its fresh paint. The school building served as quarters for the soldiers at the time this interview was conducted (January 2003).

A fourth makeshift mosque was erected near the functional deep well water pump in Bual. This pump is one of four constructed in the early nineties by DPWH using the Congressional Funds of Congressman Anthony Dequina. Three others were destroyed in the all-out-war in 2000.

A newly-built mosque in Manili, Carmen, North Cotabato was bombed just a few days before this interview in late January 2003. Photo courtesy of GOP-UN Multi Donor Programme

A newly-built mosque in Manili, Carmen, North Cotabato was bombed just a few days before this interview in late January 2003. Photo courtesy of GOP-UN Multi Donor Programme

“When UNDP came, we had a taste of outside assistance,” says Bai Lavaia, “we were organized, we were made to understand our rights as a people and as a community.” Bai Lavaia, 58, is herself a mother figure and is known to many Carmen residents. She won her Kagawad post without campaigning or spending a single centavo. (By UNDP she is referring to the Government of the Philippines / United Nations Multi-Donor Programme that offered development assistance to war-affected communities right after the signing of the GRP-MNLF Final Peace Agreement).

She takes pride relating how, as an athlete in her youth, she ran with Mona Solaiman; and who among her classmates are doing well in their respective careers. “Kaklase ko sa high school yan si PSWD Officer Zaida Rensulat (Provincial Social Welfare Development Officer Zaida Rensulat was my classmate in high school,” she beams. The two interact often since PDAs (Peace and Development Advocates) help the Department of Social Welfare and

Development in the distribution of relief assistance to internally displaced persons (IDPs).

As PDA, Bai Lavaia goes about her community work as a partner of the UN Volunteer on the ground in facilitating development activities.

The author takes notes of the responses of PDA Babu Lavaia Aliudin in Manili, Carmen, North Cotabato on the plight of the evacuees. Photo taken January 30, 2003 courtesy of GOP-UN Multi Donor Programme

The author takes notes of the responses of PDA Babu Lavaia Aliudin in Manili, Carmen, North Cotabato on the plight of the evacuees. Photo taken January 30, 2003 courtesy of GOP-UN Multi Donor Programme

Rehabilitation started in 2001 with the help of the GOP-UN/MDP3 that saw to the convergence of services of the local government units and the line agencies of the government. More core housing units were constructed with the help of the programme. A Barangay Development Planning through Participatory Rural Appraisal was conducted in August 2002 to address the community’s needs.

The GOP-UN/MDP3 recognized the historical significance of Manili, thus making it a Relief and Rehabilitation community and consequently a Peace and Development Community, having been constantly torn by conflict and in dire need of community building.

As a PDC, it has undergone community organizing and capacity-building training activities facilitated by the programme. GOP-UN/MDP3 also linked the community to existing government structures and non-governmental organizations to address the gaps.

“With the Mayor being able to find a willing partner to develop Manili, he has committed several projects and has even implemented some,” Bai Lavaia

continues. “He had the road bulldozed and filled with limestone so that it will be passable even during the rainy season.”

“LEAP-ELAP (Livelihood Enhancement and Peace program of USAID) has also

provided us with farm inputs,” says Barangay Captain Ting Nagli, “but we don’t have post-harvest facilities with which to store the corn. We just cover it with tarapal (plastic sheets). But it’s still insufficient. Because of the humidity the corn still suffers butikol (corn blight) thus decreasing its market value. Plus we have to pay for transportation.”

Mango seedlings provided by the plant-now-pay-later scheme of the Department of Agriculture is now growing steadily and is expected to bear fruit in three years.

A survey has been done for barangay electrification and endorsed to the provincial government.

Manili is still wanting in social services, infrastructure and economic development. “The Barangay Development Planning using the participatory approach will help the residents appreciate the importance of working together towards a common goal,” says Ronillo Dusaban, UN-MDP3 Area Coordinator for Central Mindanao. “The basic role of the programme is to make existing structures work. It is important that the community must have ownership to its own efforts. We only lay the groundwork.”

“The assistance reaching us should be those that we really need. The five-year Barangay Development Plan will hopefully address the real needs of our barangay, contribute to the reduction of poverty and eventually improve the quality of life of the people of Manili,” Nagli says with a glimmer of hope in his eyes.

Postscript: When the war broke out in February this year, residents of Manili, already trained on Early Warning and Disaster Preparedness, played host to displaced residents from neighboring villages.

(Aveen Acuna-Gulo writes a weekly column, “The Voice” for Mindanao Cross of

Cotabato City and is a UN volunteer deployed in the GOP-UN-MDP3 assisting

Peace and Development Communities [PDC] in Mindanao such as Manili which

she visited in January, before the latest war erupted).