DAVAO CITY (MindaNews / 19 January) – The Philippine Eagle Foundation’s (PEF) carbon forest restoration team wrapped up 2020 with over 20,000 seedlings at its nursery and over 6,000 wildlings planted at the Ayala Land, Inc. (ALI) Davao Carbon Forest in Bago Gallera, Davao City.

Drone photo of the restoration area overwhlemed by Paragrass and other weeds in 2018. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Drone photo of the restoration area overwhlemed by Paragrass and other weeds in 2018. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

This restoration project aims to transform six hectares of grasslands into a lush forest full of native trees. The new trees will then absorb and store toxic carbon from the city’s air (thus the name “carbon” forests).

As “green sponges,” the trees help prevent global climate anomalies, such as freak typhoons and droughts, while also providing a home for the city’s non-human residents – its wildlife.

2020 is the second year of the Carbon Forest project. And more work is still needed.

2019 was a bad year. The region went through El Niño, and the heat parched our plots. The dry spell killed over half of our planted seedlings.

When the rains came at the end of 2019, the highly invasive paragrass (Brachiara mutica) became our next enemy. This alien weed grew so fast, it choked many of our young plants.

With better knowledge, promising labor force, and a strategic plan, we began 2020 with high optimism.

Students of Davao Christian High School and nearly 4,000 more volunteers gave a helping hand before the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Students of Davao Christian High School and nearly 4,000 more volunteers gave a helping hand before the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Then the Novel Corona Virus (COVID-19) hit the region in March 2020. Davao City was placed under a series of community quarantines and lockdowns. Life as we know it changed drastically, including the restoration team’s operations.

But despite the novel challenges brought about by the pandemic, the team endured and delivered. And here’s how they did it.

Hard work paid off

Three members of the PEF staff worked fulltime, and spent three to four nights a week at the carbon forest, in its improvised staff quarters during the pandemic.

Project Coordinator Maje Egento supervised the restoration work, and ensured that resources and other logistical support were available. She also liaised with ALI and our network of volunteers and benefactors. Egento also organized our online crowd-funding activities.

An officer of the 11th Forward Service Support Unit (FSSU) of the Philippine Army receiving his brithday token from his comrades at the carbon forest. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

An officer of the 11th Forward Service Support Unit (FSSU) of the Philippine Army receiving his brithday token from his comrades at the carbon forest. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Meanwhile, Nursery Officer Grace Abundo collected and nursed healthy “wildlings” of both “sun-loving” (fast-growing, pioneer) and “shade-loving” (climax) trees. Pioneer trees include Igyo, Alim, Antipolo, Talisay, and Malibago. Climax trees include Dao, Lauan, Mayapis and Malibato.

She gathered plantlets from the nearby woodlands in two ways. One is through the “bareroot” technique. She uproots 6-to-12-inch-tall seedlings and clears the roots of its soil. The bareroots are then potted in plastic bags filled with garden soil.

The other technique is through “earth-balling.” Abundo collected taller seedlings (one to two meters high) with their roots covered in a ball of soil. She then wrapped the “earthball” with banana sheaths and “hardened” them at the nurseries.

Along with over 5,000 wildlings from kind donors, the seedlings are primed for transplant. The nursery now has over 20,000 wildlings belonging to 55 kinds (species) of native trees, including fruit trees.

PEF Forester Guiller Opiso managed the restoration plots. With his long years of practicing dendrology (scientific study of trees) and forest restoration, he is our technical guy. He checks that the right species are nursed and planted, and ensures the right way to nurture trees is followed by aides and volunteers.

Bantay Bukid Forest Guard volunteers doing strip brushing at the restoration plots. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Bantay Bukid Forest Guard volunteers doing strip brushing at the restoration plots. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Opiso is ably assisted by two aides and over 200 volunteers. Together, this workforce collected and potted seedlings from the forests (wildlings), controlled the paragrass, prepared the land for planting, transplanted the wildlings, and watered and nurtured the plants.

Between March and December 2020, the team planted and cared for 6,815 seedlings in three hectares of reclaimed grasslands.

Lean and mean volunteers

At the end of 2019, we got help from nearly 4,000 volunteers. In 2020, we did not even reach a tenth of that number. The ban on travel by minors and seniors, mass gatherings, and non-essential trips reduced our manpower.

We thought we would get the same volunteer numbers for 2020, if not more. The pandemic proved us wrong.

We got helping hands from only three volunteer groups in 2020. But an increase in the frequency, length and quality of their work compensated for the small volunteer force.

Our first group of volunteers consisted of officers from the 11th Forward Service Support Unit (FSSU) of the Philippine Army. They nurtured 2,500 native trees in a one-hectare plot.

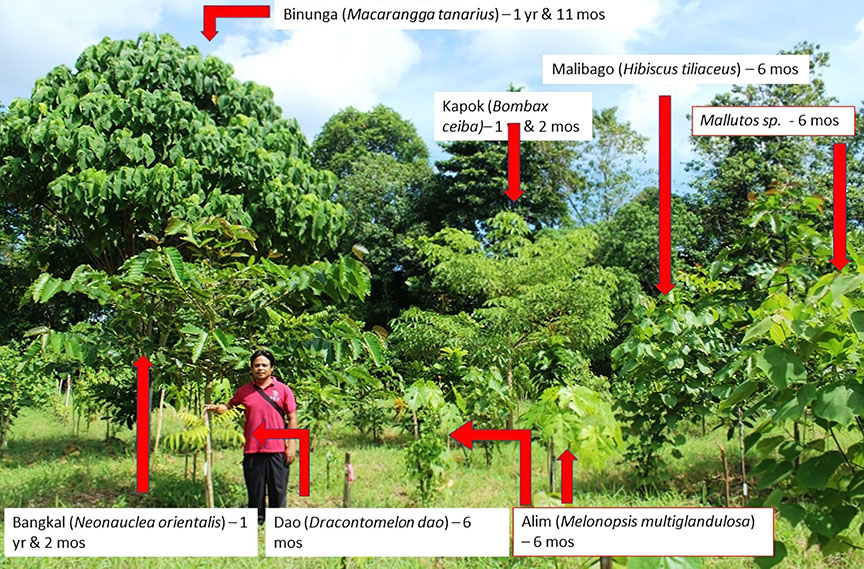

Fast growing or pioneer trees between 6 months and 2 years old in one of the restoration plots. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Fast growing or pioneer trees between 6 months and 2 years old in one of the restoration plots. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

The group “adopted” the plot in 2019. Headed by Commanding Officer Colonel Clarence Garrido, about 20 to 30 officers spent their first Saturday of each month replacing dead seedlings, trimming young trees, and cutting the weeds.

Each Saturday duty is also a gathering to greet FSSU personnel who are celebrating their birth month. A small cluster of 8 to10 FSSU staff then returned during the rest of the Saturdays to do more work.

On a few occasions, FSSU provided free rides to our forest guards and transported seedlings contributed by citizens. They also donated hand-wash stations in support of our COVID-19 prevention protocols.

Our second group consisted of Indigenous forest guards (Bantay Bukid) from five upland communities in Davao City. Since June 2020, nearly 100 Bantay Bukid volunteers from Barangays Sibulan, Tawan-tawan, Tambobong, Carmen, and Salaysay made shifts doing restoration chores at the carbon forest. Each week, six to eight volunteers spent three to five weekdays at Bago Gallera.

The first year of a plant’s life is its weakest stage. Many restoration projects failed because they neglected and invested less on this critical stage. The able-bodied and diligent men and women of Bantay Bukid maintained the plants and kept them healthy.

Healthy Malibago seedlings at the carbon forest tree nursery. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Healthy Malibago seedlings at the carbon forest tree nursery. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Our last volunteer group are mountaineers from various clubs in Davao City. They were recruited and organized by PEF Forest Restoration Aide Ramel Busa, who is also a mountaineer.

A batch of 10 to 15 volunteers worked each week-end since September 2020. They brought their own garden tools. Some lent their personal electric grass cutters, which efficiently controlled paragrass growths.

Virtual tree nurturing and fund-raising

Restoring forests is not cheap. To help raise funds, we hosted virtual “crowd- funding” events. Called the “Nurture a Carbon Forest” initiative, benefactors adopted one seedling for P500. This partially covered the nursery care, land preparation, planting, and six-month maintenance of a single young tree.

Crowd funding proceeds also subsidized the food and transportation of Bantay Bukid volunteers coming from the remote Mt. Apo barangays. Donations covered commute costs and their three- to five-day duties at Bago Gallera. Ayala Land matched these contributions by covering the salary, transportation, food allowances, and equipment needs of full-time and part-time PEF staff who managed the carbon forest year-round.

Forester Guiller Opiso leading a group of volunteers during a nature walk session. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Forester Guiller Opiso leading a group of volunteers during a nature walk session. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

PEF hosted three “Nurture-a-Carbon Forest” webinars in 2020. Each webinar showcased three virtual experiences for the participants – (i) tour of the ALI Davao Carbon Forest woodlands, showcasing some of its wildlife inhabitants, (ii) overview and tour of the six-hectare restoration plots, and a (iii) tutorial on nursery care, and planting and maintenance of the “wildlings.” Participants also interacted with PEF restoration staff and ALI representative through an open forum.

A total of 980 benefactors or “carbon warriors” from four organizations participated. These organizations were the (i) Stella Maris Academy of Davao Batch 1995, (ii) Ayala Land Inc (Inc) personnel and partners, (iii) Ateneo de Davao University Environmental Science students and the (iv) Philippine Science High School-Southern Mindanao Campus Batch 1995.

The Student Environmental Alliance of Davao (SEAD) also hosted an online benefit concert on December 19, 2020. Joey Ayala and other national and local artists performed at this virtual gig. SEAD donated an electric grass cutter and garden tools from the funds raised by this concert.

Rain is grace

An important element of nature also cooperated. In contrast to the parched weather of 2019, the carbon forest received plenty of rains in 2020.

An El Niño (dry) spell struck Mindanao from February to April in 2019. To save the young plants, they were watered diligently. We laid down a network of firefighting hoses across the plots and filled steel drums with water suctioned by a generator from the nearby creek. Water was then manually hauled and sprinkled to our plants.

Forest restoration aide Ramel Busa in PPE suit prepping for a day of grass cutting. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Forest restoration aide Ramel Busa in PPE suit prepping for a day of grass cutting. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

But even the creek dried up eventually. Before the rains in June, over half of our plants had already perished.

Thankfully, rain water in 2020 was plenty. Although most of the plots got occasionally flooded, older wildlings planted in 2018 and 2019 survived getting soaked.

At our new plots, our modified “mounding” technique spared fresh transplants from drowning. “Mounding” is piling soil to form a mound, and digging a deep canal at its perimeter. We then planted a seedling atop the mound. In an experimental plot, this method saved the seedlings from floodwaters.

But digging the mounds manually is slow and difficult in flooded plots. Because La Niña is forecasted to last until the first quarter of 2021, we deferred planting in new and vacant plots.

Meanwhile, we transplanted “shade loving” species between young trees (interval planting) at our old plots. We planted dipterocarp trees such as Lauan, Mayapis, and Malibato. Maintaining “interval” plants are easier because paragrass and other invasive weeds were already shaded out by the canopies above.

Way forward for 2021

The PEF restoration team will level up its work for 2021 in two ways. First, we will explore the use of an excavator in creating more mounds at new plots faster. Excavators are the typical machinery for mounding at wet restoration sites abroad.

Over half of the six-hectare restoration site experience flooding. We will knock on the doors of possible benefactors who can either lend an excavator or provide funds to rent one.

Students of the Ateneo de Davao University Environmental Science Students interacting with the restoration team on site during a virtual tree planting webinar. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Students of the Ateneo de Davao University Environmental Science Students interacting with the restoration team on site during a virtual tree planting webinar. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Second, we will accept more volunteers for 2021, but under strict compliance of basic health protocols. Such rules will include wearing of facemasks, physical distancing of at least one meter between volunteers, and hand-washing with soap and water. Also, volunteers and PEF staff deployed at the restoration site should not exceed 25 people.

These, and other protocols, comply with Executive Order No. 69, series of 2020 issued by Mayor Inday Sara Duterte to curb the spread of COVID-19.

(Jayson C. Ibanez is the Director of Research and Conservation at the Philippine Eagle Foundation. He is also a Senior Lecturer at the University of the Philippines in Mindanao.)