Davao: Reconstructing History from Text and Memory, 2nd edition

Author: Macario D. Tiu

Research and Publication Office, Ateneo de Davao University, 2021, 571 pages

Postcolonial feminist scholar Saidiya Hartman’s revelatory essay titled “Venus in Two Acts” (2008) probes the politics and limits of the archives: how they can distort and silence narratives of African girls in a slave ship. The archives have been cruel in erasing and muting the personal histories and memories of the African girls. In a cogent analysis, Hartman offers a new way of looking into the archives by “straining against the limits … to write a cultural history of the captive, and, … enacting the impossibility of representing the lives of the captives precisely through the process of narration. … this writing practice is best described as critical fabulation” (11).

The fraught imagination of Hartman’s method, therefore, demands dissecting the gaps and filling in the closures to the wounds left by the colonial and state orders. One should partake in making and remaking the archives that will interrogate, challenge, and in Hartman’s utterance, critically fabulate. The outcome of the fabulation is deemed to be a “recombinant narrative,” which would converse with the lifeworlds enmeshed in the conjugating tenses of the past, present, and future.

Hartman’s critical fabulation resonates with Macario Tiu’s concept of “reconstructed history,” which makes use of local narratives and speculations in framing and reframing, presenting and representing, and constructing and reconstructing history by using the sources that can be culled in the communities such as oral traditions, folk stories, legends, Muslim tarsila (genealogies), gossips, testimonies, and other forms of folk lores and pieces of knowledge. This method already has its traces evident in Tiu’s early work Davao 1890-1910: Conquest and Resistance in the Garden of the Gods, first published by the UP Center for Integrative and Development Studies in 2003, but is fully exhausted in the first edition of Davao: Reconstructing History from Text and Memory published by the Research and Publication Office of the Ateneo de Davao University in 2005 and winner of the Manila Critics Circle’s National Book Award. In the two books, Tiu uses the people’s stories and memory documents to fabulate and engage with history and archives.

In 2021, Tiu embarked on the effort to rework the knowledge, values, and quality of discourse by expanding, revising, and reprinting the second edition of Davao: Reconstructing History from Text and Memory. At the heart of the new edition is the opportunity to rectify certain errors, contribute further information in the production of knowledge, and search for alternative critical locus and locution in updating Davao history. The new, revised, and second edition has additional 180 pages with interesting details that Tiu has continuously gathered from the communities 15 years after the first edition.

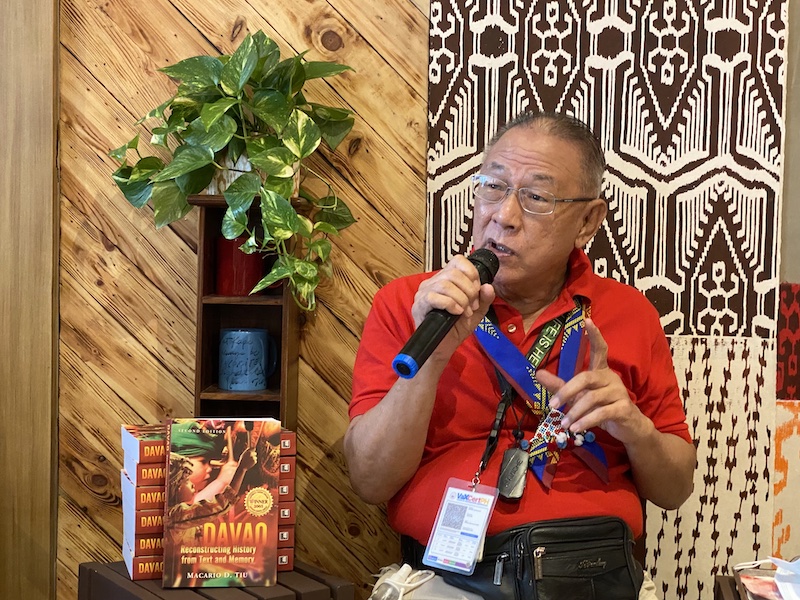

Dr. Macario Tiu narrates why he wrote a second edition of his book, “Davao: Reconstructing History from Text and Memory” during the Throwback Thursday Conversations of the Davao Historical Commission on 18 August 2022 at the Rodgen Inn in Davao City. The first edition,. published in 2005 won the National Book Award for Hisoty in 2006. MindaNews photo by CAROLYN O. ARGUILLAS

Dr. Macario Tiu narrates why he wrote a second edition of his book, “Davao: Reconstructing History from Text and Memory” during the Throwback Thursday Conversations of the Davao Historical Commission on 18 August 2022 at the Rodgen Inn in Davao City. The first edition,. published in 2005 won the National Book Award for Hisoty in 2006. MindaNews photo by CAROLYN O. ARGUILLAS

The heft of the anthology still resides in Tiu’s objective to “theorize” in Mindanao Studies by speculating the roots and tracks of conquest and state formation using our own folkloric materials and sometimes borrowing from the influences of Louis Althusser, Edward Said, Homi Bhabha, and other Marxist theorists. What the book tries to pose in this theorizing is the imperative need to decolonize Filipino nationalist historiography, and one way to do it is by mapping out the connections of Davao and its adjacent regions to the various events in Philippine colonial narratology. One may also infer that Tiu is encouraging researchers and scholars to accord Davao and its nearby regions the same way the mainstream discourses pay attention to the events and details in the national capital.

The introduction to the book implicitly sets a direction that is coordinated with the entire structure of the project. It suggests historiography that “deconstruct the pernicious biases of a colonially-motivated history and reconstruct it based on our people’s point of view” (xviii). The design of the anthology is to listen closely and search for the kernel of historical facts and truths in the so-called “naive stories” othered by traditional historical sources. Tiu is of the mind that the stories in the Indigenous and settler cultural communities should be decoded, evaluated, and interpreted not against but along the grain as they can supplement clues needed for a fuller and clearer understanding of history amidst its convoluted syntax and erroneous construction.

The second edition is still divided into five chapters. The first chapter details the historical highlights in the Davao region from the precolonial period up to the presidency of Rodrigo Roa Duterte. The part reveals the archeological excavations in Talicud Island in Davao Gulf and Davao Occidental, and highlights how the Davao region extending to the Balut Island in the southeastern part of Mindanao could formerly be attributed as part of the Magindanaw Buayan sultanate.

The succeeding chapter provides rich data and discourse on the various “tribes” that inhabit the Davao region.

It is interesting to stress how Tiu retained the nomenclature “tribe” to refer to the Lumad (Indigenous peoples). On the one hand, the Latin origin and Roman Republic imagining of the word “tribe” has evolved into a derogatory term for non-European people as it now connotes “fossilization.”

On the other hand, one may deduce that Tiu’s usage of the word “tribe” is a product of rigorous and careful research that is judicious in its assertions. Tiu veers away from using “ethnolinguistic group” because the data in the community say that some Indigenous groups may have different identifications and belief systems but still speak the same language, such as the Ata, Matigsalug, Langilanon, and Talaingod Manobo. That said, categorizing groups according to their “ethnicity” and “language” (ethnolinguistic) would be limiting and reductive; in addition, the Indigenous communities called themselves “tribes.”

The third chapter recounts the stories of the settlers who are imagined not in the traditional simplistic and summarized presumption of being the “culprits” of the “minoritization” of the Indigenous cultural communities but also as agents of how the Davao region has evolved and contoured its present shape.

In the following chapter, the imagined real-life heroes of Davao are enumerated – from the Spanish conquest up to the Martial Law era. Tiu rescues the Lumad chieftains (Datu Bago, the old woman of Baganga, and Mangulayon), activists, and civic workers who fought against the different forms of colonization and dictatorship. Finally, the last chapter exemplifies the gargantuan amount of folk stories and narratives that are vital elements in filling in the gaps of history.

What is interesting about the second edition is the rectification of the previous errors, such as the details about the Maitum jar, in which Tiu picked the Blaan over the Tboli as the makers of the human-shaped pottery in the first edition. Here, Tiu corrects himself by tending over the Tboli as makers of the Maitum jar by referencing local lores and stories as compelling pieces of evidence to support his theory.

There are also terminologies deemed to be summarized and depreciative that are reworked such as the usage of “banditry” to refer to the Blaan resistance against the settlers in the 1960s era. The conflict that transpired in Davao del Sur was an outright Blaan uprising and not “banditry” to protect their yutang kabilin (ancestral land). In the parlance of Tiu, “[M]y discussion of the Blaan in the first edition of this book was very inadequate” (106).

Tiu has also rectified the date when the term “Lumad” was first used. Some interlocutors in Mindanao Studies point to the use of the terminology in the 1980s period, but Tiu’s own investigation led him to conclude that Lumad’s first usage can be traced back to the late 1970s when Francisco F. Claver, SJ, then bishop of the Bukidnon diocese in Mindanao, summoned a meeting under the Mindanao-Sulu Conference on Justice and Development (MSCJD) to conduct an all-Indigenous Peoples consultation with representatives from various groups.

The crux of the matter in the second edition, however, is the interesting new additions about the political and cultural landscape of Davao. Tiu expanded the historical highlights of the region up to the mayoral and presidential post of Rodrigo Roa Duterte, to whom the peace and order in what was once tagged as the murder capital of the Philippines was attributed. The rumors have it that Duterte supported the Davao Death Squad in making extrajudicial killings (EJKs) to pacify the crimes in the city, which mostly victimized “suspected” criminals. This significant addition maps out that decoding Duterte’s rise to power and the current national affliction we are enduring entails a deep understanding of how the state has left Davao and its adjacent regions in the detritus of the nation’s dreams and aspirations.

Other important additions worth noting are the write-up on Bibiaon Ligkayan Bigkay, the first Ata woman to earn the distinction as chieftain because of her competence in handling “paghusay” concerns. Bai Bibiaon, as she is fondly called, has stood her ground to lead protests against the threats of mining companies in the remaining forests of the Pantaron Mountain Range. Tiu has also mentioned the plight and struggles of the Nagkahiusang Mamumuo sa Suyapa Farm (NAMASUFA) or the SUMIFRU farmers who complained about their harsh working conditions, in which the “pakyaw” or piece rate system replaced the previous hourly rate system. These narratives are vital in how the Indigenous and settler cultural communities assert the need for self-determination and the universal right to breathe.

In the list of local heroes, Tiu has also added more names who fought against the different forms and shapes of dictatorship during the Martial Law period, such as Soledad “Nanay Soling” Duterte who was one of the faces of the Yellow Friday Movement in Davao. The movement ushered for weekly protests participated by various sectors that helped generate nationwide mobilizations leading to the EDSA People Power revolution in 1986. One poignant story in this section is that of Ricardo P. Filio, who made use of his privilege to forward the causes for socio-political changes. Ricky dedicated his life to the countryside by participating in the armed struggle. His death, however ill-fated, is not a failure but a step in the right direction. Ricky’s life and passion have been celebrated and used in various literary works, including the poem “Ricardo Filio, 21” and the highly-acclaimed short story “Sky Rose.”

Tiu has also updated the list of folk narratives in Chapter 5 from 64 to 80 stories. One may surmise that Tiu was inspired by Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano by retelling lores and narratives in reconstructing the history of the Davao region, but Tiu’s collected narratives are also products of critical acumen and astute research. The inclusion of “Andarapit” is a significant addition to the lores as it limns on the mélange of sexuality, pleasure, life, and even life after life. Another interesting addition is “Why the Bats Hide in Caves,” which reminds us about the value of “shame” and the impediment of being neutral in times of distress.

Perhaps, the most riveting part of the second edition is the update on the Manurigaw or the White Mandaya at the Manurigaw River in the Davao Oriental-Davao de Oro border. Tiu, in a fashionable vignette, narrates the uncanny of how a community with grey-eyed and blond people is reclused in the forest of Davao. The book offers different possibilities about the White Mandaya community by continuously uncovering its origins through unearthing documents about the Santa Maria de Parral of the Loaisa expedition that got lost in Davao Oriental in 1526, and to borrow Saidiya Hartman’s words, by critically fabulating. It is in this fabulation that Tiu can persistently reconstruct and reclaim our histories.

Overall, the second edition of Davao: Reconstructing History from Text and Memory is a valuable text that reminds us about the importance of reconstructing the past, reckoning with the present, and reimagining the future of the nation. Tiu reminds us that it is within reach of our arms to revise, rewrite, and reword a world anew – in the present progressive tense of writing and dreaming.

(Jay Jomar F Quintos is associate professor of literature at the University of the Philippines. This book review first appeared in the most recent issue of Tambara Journal of the Ateneo de Davao University. The second edition of Macario Tiu’s Davao: Reconstructing History from Text and Memory is available at the Ateneo de Davao University Bookstore).