DAVAO CITY (MindaNews / 22 November) — Seven individuals of the “critically endangered” Philippine eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi were rescued since the COVID-19 lockdowns and quarantines. One died of malnutrition; three were released back to the wild; two are non-releasable, and one is primed for release next year. Here are their stories.

“Siocon”

A farmer found the weak bird hiding in the bushes at a forest edge in Siocon, Zamboanga del Norte in April. He cradled the animal, hopped on a tricycle, and surrendered the feeble bird to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). But the country was at the height of travel restrictions, and Siocon is a long, 20-hour drive from Davao City. The Philippine Eagle Foundation (PEF) rescue team could not get to the bird. Eagle Siocon must be medicated and rehabilitated on-site.

Philippine Eagle Siocon during turnover to DENR 9 by his rescuers. Photo courtesy of DENR 9

Philippine Eagle Siocon during turnover to DENR 9 by his rescuers. Photo courtesy of DENR 9

Mobile technology and social media became vital. The PEF and DENR worked together to restore Siocon’s health via video conferencing, phone calls, and text messages. The bird weighed 3.9 kgs, is about 3-4 years old (barely sexually mature), and is probably male.

The telemedicine worked. Siocon’s release was greenlighted after her virus tests came out negative. With travel passes from five provinces and two cities, the PEF team drove 20 hours across 15 quarantine checkpoints to attach a radio transmitter and a solar-powered GPS/GSM tracker on the bird. The trackers allow monitoring of the eagle’s movement and safety for the next three to four years.

On the morning of May 21, a day before the world celebrated “International Biodiversity Day,” Siocon flew to his freedom. Since his release, Siocon has settled inside the protected forests of Baliguian town, three kilometers away from his release site.

“Palimbang”

In April, DENR and town officials of Palimbang, Sultan Kudarat saved an eagle from a mob of curious residents who poked and taunted the poor animal while it was tied by the leg at the center of a village plaza. The bird was a juvenile eagle – a little over a year old – who still depends on its parents for food. A local saw the bird on the forest floor a few days back.

But travel was very difficult because of the pandemic. Just like Siocon’s case, on-site rehabilitation was the only option. Palimbang Mayor Joenime Kapina took custody of the eagle, and the local DENR tried to help restore the eagle’s health.

Dr. Ana Lascano injecting fluids to severely dehydrated eagle Palimbang. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Dr. Ana Lascano injecting fluids to severely dehydrated eagle Palimbang. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

But the bird lost a lot of weight, and had not eaten for days. On May 7, the DENR rushed the bird to the Philippine Eagle Center (PEC) in Davao City for emergency medical attention. At the center, all hands were on deck to stabilize the bird. The usual x-ray, and blood workup were skipped because the bird was so fragile; a pierce of a needle through its brittle veins might bleed it to death. The bird weighed 1.8 kgs – severely underweight by eagle standards. It was very weak and sunken, and its almond-shaped eyes reflect severe dehydration. Its body condition score (BCS) was rated at 1 (very poor), which means the bird was just bones and skin.

PEF Vet Consultant Ana Lascano tube-fed the bird with meat solution, and gave food supplements and antibiotic. The bird was then isolated at the PEC quarantine facility to rest and recuperate. But the bird didn’t make it. Eagle Palimbang died near midnight of May 9.

“Makilala-Hiraya”

It was June 8, and a link to an FB post showing a captive Philippine Eagle was sent to me via messenger. I clicked the link and the photo of a manhandled eagle appeared. The bird was in Barangay Kisante in Makilala, North Cotabato. Three locals rescued the bird after it was pinned to the ground by a flock of aggressive crows. I phoned DENR North Cotabato and they rushed to Kisante to remove and secure the bird away from the noisy crowd of locals while the PEF team drove to Makilala.

The bird was standing on an improvised perch inside the community jail when the PEF team arrived. Animal Keeper Adriano Oxales entered the cell, sized-up the bird, and swiftly grabbed its legs the moment it looked away. With extra help, Oxales successfully restrained the bird.

Makilala-Hiraya during release. Photo by Gideon Zafra, LGU Makilala Information and Communications Office

Makilala-Hiraya during release. Photo by Gideon Zafra, LGU Makilala Information and Communications Office

But the bird also got a piece of its handler. After Oxales caught its legs, the aggressive eagle retaliated with a quick bite at his forehead. Oxales emerged triumphantly from the cell with the fully restrained eagle, but with a shallow cut above his left eye.

PEF Vet consultant Bayani Vandenbroeck made a quick check-up and injected the bird with fluids and vitamins as emergency nourishment. He also treated Oxales’ cut with topical antiseptic. The team drove off proud, with an apparently healthy bird.

After getting cleared of viral diseases, and over a month of rehabilitation at the PEC, the bird was finally released back to its forest home in Mt Apo on July 28. The bird is female, and perhaps 4 years old. She was named “Makilala” after her rescue area, and “Hiraya” – an old Tagalog saying which translates to “may your heart’s wishes come true.” She was set free with a GPS/GSM tracker on her back and her release was live-streamed on social media. As of October, Makilala Hiraya was within the ancestral domain of the Indigenous Obu Manobo in Magpet town, 13 km north of her release site.

“Mal-lambugok”

It was July 30, and Agusto Diano, Tribal Chieftain of the Mandaya community in Caraga, Davao Oriental reported a captive eagle. A fellow Mandaya farmer trapped the bird after the eagle reportedly hunted all of the farmer’s four piglets. We drove seven hours the following day, and took a three-hour motorcycle ride over the worst road you can imagine to get to the remote village of Tagbanahao where the bird was kept.

At Tagbanahao, the bird was inside a chicken cage right in the middle of a noisy crowd of villagers. There was no social distancing and very few were wearing a face mask. We restrained the already super-stressed bird, and left the community before dusk.

Philippine Eagle Mal’lambugok during xray in a hospital in Davao City. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

We walked to spare the bird from the back-breaking motorcycle ride. With its eyes covered by a leather hood and its body wrapped in elastic bandage, the bird was cradled like a sleeping baby. We reached our car after two hours of downhill trek with only headlamps lighting our way. After a quick inspection by Dr. Lascano, we drove back to Davao City.

But the bird manifested psychological trauma at the PEC. It went restless at the slightest human sound. Also, it did not eat for five days, and its weight dropped from 5.8 to 4.8 kgs. Thankfully, she began eating on the sixth day, and each day thereafter. She slowly regained her weight.

Passing x-ray and agility tests and clean of deadly viruses, eagle Mal’lambugok was released on September 26, as the world celebrated the World Environmental Health Day. She was cheered on by over 100 guests and local residents. Before the release, Indigenous forest guards prayed to the forest spirits for the bird’s health and safety.

“Balikatan”

A concerned citizen sent PEF a message on August 28 about another captive eagle in Bacuag, Surigao del Norte. Ryan Orquina, a Bacuag resident, bought the bird from an Indigenous Mamanwa trapper. He paid 8,000 pesos but he believes it’s a small price to pay considering that it meant saving one individual of our national bird from possible serious, if not fatal, injuries.

After being tested negative for COVID-19, and their medical certificates secured, PEF vet Ana Lascano and her rescue team left Davao City past midnight of August 29. The team rendezvoused with DENR staff in Butuan City and the composite team drove further north to Bacuag town.

Philippine Eagle Balikatan showing its opaque and blind left eye. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Philippine Eagle Balikatan showing its opaque and blind left eye. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Orquina confessed he had the bird for almost three weeks. And that he fed it with chicken and rats, and also sea snakes caught from his fish pens. He also thinks the bird was kept for several weeks by its Mamanwa captor before the Indigenous fellow sold it.

The bird weighed 3.8 kgs, immature (3 – 4 years old) and is male. Interestingly, the bird was docile. It was restrained easily. It seemed comfortable with people and is used to being handled. At a hospital in Davao City, x-ray showed neither injuries nor abnormalities. Disease tests were also negative.

The bird seemed healthy, but it was half blind. Standard ophthalmic test showed that its left eye can’t see. Sadly, the other eye is also showing early signs of eye infection. Our rehabilitation team at the PEC is trying to save the bird’s right eye. But with its current condition, he could no longer be released back to the wild.

“Caraga”

A day before we released eagle “Mal’lambugok,” I got a phone call about another eagle trapped at Tagbanahao – the same place where Mal’lambugok was rescued from. The captor claimed that the new bird killed his piglet and he retaliated by trapping the bird.

We left Davao City past midnight on September 26 to release “Mal’lambugok” and arrived in Caraga at dawn. PEF Vet consultant Bayani Vandenbroeck examined the new eagle, while we drove further up the mountain to release Mal’lambugok.

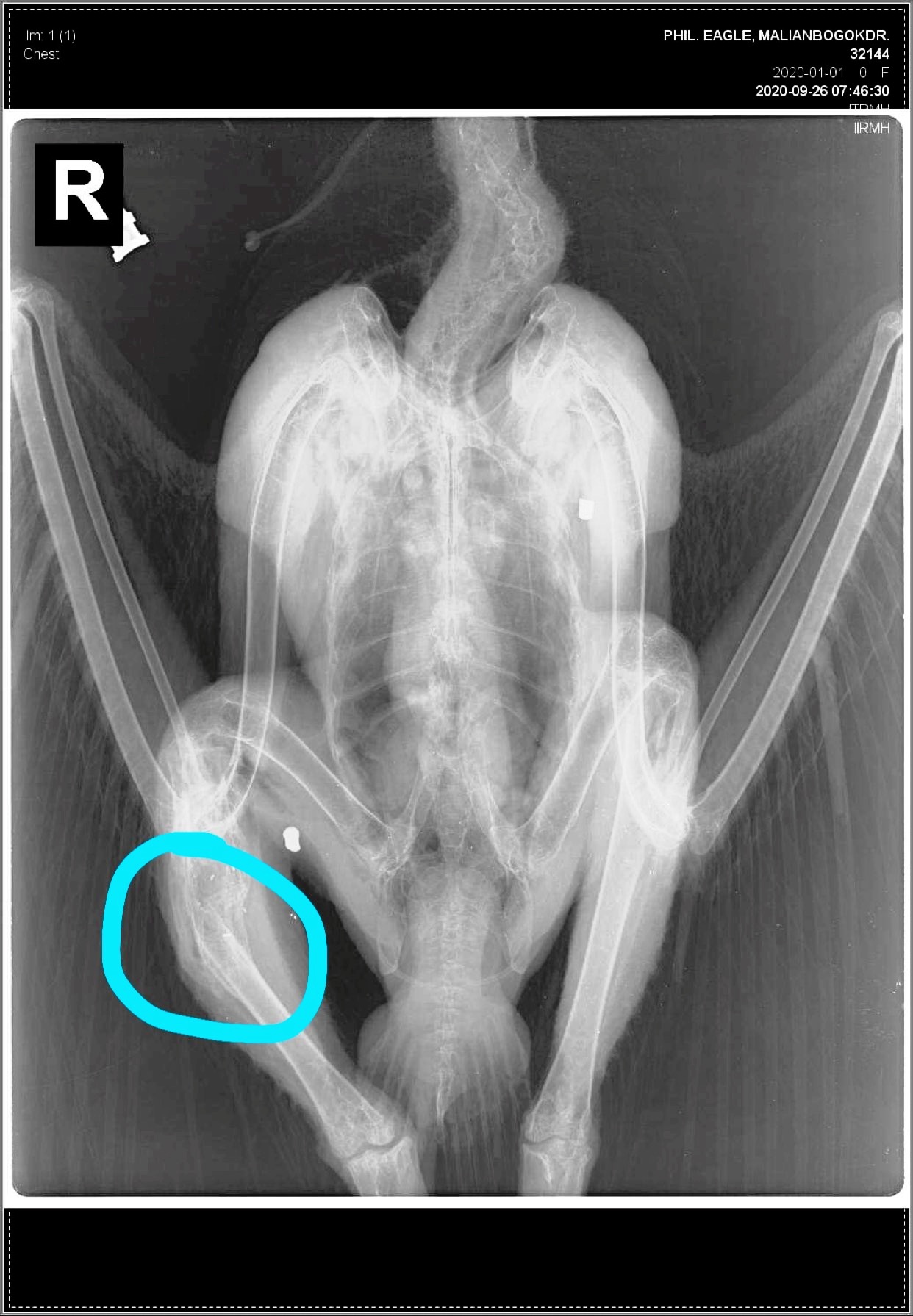

X-ray plate for Philippine Eagle Caraga showing right leg fracture and two airgun pellets. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

X-ray plate for Philippine Eagle Caraga showing right leg fracture and two airgun pellets. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

But the new bird was in bad shape. It was underweight and dehydrated, and had not eaten for days. We brought the eagle patient with us to Davao City after Mal’lambugok’s release.

In Davao City, x-ray plates revealed more of the new eagle’s miseries. It had two bullets inside its body; one at the left chest, and another at its right thigh. The bird also had a fractured right leg, which explained its awkward posture.

Contrary to the captor’s claim, it looks like he had the bird for quite a while now. An eagle with a damaged leg could not hunt and survive in the wild. The only way it could make it this far is if someone caged and fed it. The DENR is gathering evidences for a possible filing of a criminal case against the captor who violated wildlife laws.

“San Fernando”

Three people, in succession, reported another immature eagle needing rescue last October 4. The bird was accidentally caught in a native trap at the Pantaron mountains of San Fernando town in Bukidnon last October 1. LGU Bukidnon and DENR staff handed over the bird to PEF on October 5 in Malaybalay City.

Handfeeding of eagle San Fernando. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Handfeeding of eagle San Fernando. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

The bird was transported to PEC and was examined. It weighed 3.9 kgs, had good muscles and appeared to have no serious injuries, although x-ray showed an air gun pellet lodged at the right wing of the bird.

Because it had not eaten for four days, PEF Animal Keeper Dominic Tadena hand-fed the bird with fresh chunks of meat laced with supplements. The bird’s eyes were covered by a leather hood, but the starving bird gobbled up any meat that touched its beak. Half-way through the feeding, it plunged its face into the meat bowl and ate voraciously by itself. The bird is recovering well and can be released next year.

Collaboration and technology are key

“This is the highest number of eagle rescues in a span of just seven months” said Dennis Salvador, Philippine Eagle Foundation Executive Director. “We are very glad that despite the pandemic, six of these seven precious birds were saved, with three eagles released back to their forest homes” he added.

Collaboration was one key ingredient: from concerned citizens reporting an eagle in distress; to groups cooperating to rescue, medicate and bring back an eagle’s health; to releasing and monitoring the birds with the help of trained community volunteers and their village and Indigenous organizations.

Philippine Eagle Siocon with radio and GPS@GSM trackers strapped on his back. Photo courtesy of DENR 9

Philippine Eagle Siocon with radio and GPS@GSM trackers strapped on his back. Photo courtesy of DENR 9

Another is technology. With the help of social media, Siocon’s situation led to the first telemedicine case in the program’s history of eagle rescues and rehabilitation. Online platforms also enhanced the reporting of sick or injured wildlife needing rescue. More people seemed to have become mindful of their environment during the pandemic, and travel restrictions seemed to have given them spare time to observe and report wildlife in distress.

Instrumenting released eagles with lightweight radio and GPS trackers helped tremendously in keeping tab on released eagles. Field-based radio tracking is a user-friendly tool. Trained local volunteers can easily do it. Solar-powered GPS-GSM trackers installed on each bird back-pack style, on the other hand, sends accurate geographic locations of the instrumented birds to PEF. We can then send these GPS readings to field biologists and volunteers to aid them in “homing-in” and observing a released bird.

Clear and present danger

But eagle offenses, such as the intentional trapping and selling of eagle “Balikatan,” and the shooting of eagle “Caraga,” raised a red flag. These are assaults against the “protected” status of our national bird.

The Philippines’ RA 9147 or the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act penalizes offenders who possess, harm or kill endangered wildlife. Destroying their nesting and feeding areas are fined too. If someone kills a “critically endangered” species like the Philippine eagle, a wildlife criminal can be jailed for a maximum of 12 years and fined a total of one million pesos.

Photo from the Philippine Eagle Foundation’s website.

Photo from the Philippine Eagle Foundation’s website.

“We have just launched a full investigation into these cases” said Ricardo Calderon, DENR Assistant Secretary for Climate Change and concurrent Director of the Biodiversity Management Bureau of DENR. “If proven guilty, the perpetrators will face the full extent of the law,” he wrote.

The late Dioscoro Rabor, Father of Philippine Wildlife Conservation, once said that the “Philippine Eagle is as Filipino as we are all Filipinos.” As our emblem, every individual of our national bird has a right to a decent life, just like each citizen of this country. Our wildlife laws protect that fundamental animal right.

“We urge the public to help step-up wildlife law enforcement by reporting violations to your respective DENR regional offices. And should any citizen wish to volunteer as a wildlife law enforcer, they can also contact the nearest DENR office, sign-in, get trained and be deputized as Wildlife Enforcement Officers,” Calderon said in closing.

(Jayson C. Ibanez is the Director of Research and Conservation at the Philippine Eagle Foundation, and also a Senior Lecturer at the University of the Philippines in Mindanao)