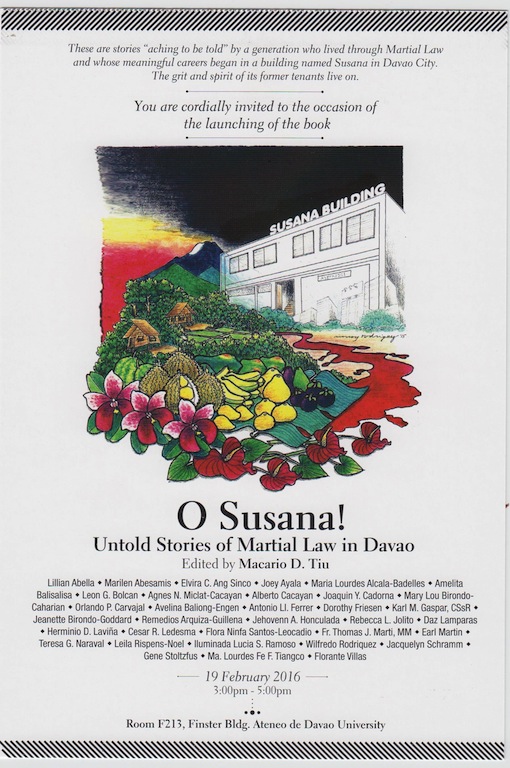

(Introduction by Dr. Macario D. Tiu to the book, “O Susana! The Untold Stories of Martial Law in Davao,” written by 34 authors and edited by him. Published by the University Publication Office of the Ateneo de Davao University, “O Susana” will be launched tomorrow, February 19 at 3 to 5 p.m. at the university’s F213, Finster Building. Dr. Tiu, historian and Palanca awardee, is also the Director of the UPO)

DAVAO CITY (MindaNews/18 February) – When I was asked by Karl Gaspar to edit the articles for the “Susana” book, I readily agreed. I had heard about this book project some two years back. Its moving spirits — Len Abesamis, Jet Birondo- Goddard, and Agnes Miclat-Cacayan —had been conducting a series of workshops and writeshops to put together stories of Martial Law by church and other social development workers whose offices were housed in the innocuous Susana Building located along J.P. Laurel Ave., Davao City. The first workshop of the Susanistas, as they call themselves, was held in the United States. More workshops followed in various locations in Davao over a period of two years.

From what I heard, the workshops were often teary occasions not only for bonding but also for meditation and memory-sharing so that the events that happened a distant four decades ago could be refreshed and written for the new generations of Filipinos to read and ponder. As we all know, it is one thing to tell stories, and another thing to write them. But Len, Jet, and Agnes—dubbed as the Tres Marias—persisted in reminding, cajoling, and mentoring the Susanistas, and succeeded in having a number of them write their stories.

Reading the stories, I immediately saw their historical value in showing, on the one hand, the arbitrariness and brutality of the Marcos Dictatorship (1972-1986), and on the other hand, the silent courage of church and ordinary folks in Mindanao in defying Martial Law. These are stories of people who chose to work aboveground when Martial Law was declared, as distinguished from those who worked underground or fought in the countryside. But as their stories demonstrate, working aboveground was no easy matter, either, as the aboveground spaces were not only suffocating but also very dangerous.

Reading the stories, I immediately saw their historical value in showing, on the one hand, the arbitrariness and brutality of the Marcos Dictatorship (1972-1986), and on the other hand, the silent courage of church and ordinary folks in Mindanao in defying Martial Law. These are stories of people who chose to work aboveground when Martial Law was declared, as distinguished from those who worked underground or fought in the countryside. But as their stories demonstrate, working aboveground was no easy matter, either, as the aboveground spaces were not only suffocating but also very dangerous.

Indeed, in the context of Martial Law when thousands were imprisoned, tortured, and killed, and the military could raid any convent and shoot at priests, I could only marvel at the ingenuity and creativity of the Susanistas in carrying out their mandate to conscientize across Mindanao. Motivated by the Mindanao church that had earnestly begun to implement the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, they not only braved hazardous terrain, they also had to contend with military and paramilitary troops who could take an unwonted fancy on them. It was a thrill to read how they negotiated and maneuvered within the spaces of Martial Law, and how they pushed the envelope to tell the truth: Jeje going into a remote mining town in Zamboanga peninsula to conduct a creative dramatics workshop among miners, Jet tiptoeing gingerly through a booby-trapped mountain trail, Elvie dodging bullets in Jolo, Len escorting an escaped political detainee to safety.

As there are more than thirty authors in this anthology, with some of them writing a full-blown essay for the first time, expect more than thirty different styles of writing. But regardless of the manner of writing, all of them are authentic voices. There’s Agnes’ conversational letter to her young sons, Jackie’s lyrical reflections, and Nonoy R.’s report in Bisaya of a creative writing workshop among peasants. All are deeply-felt personal experiences during the terrible years of Martial Law. That is why there are also tributes to people who were exemplars of compassion and service, and tributes to people who stood as pillars of strength when confronted directly by the minions of Martial Law: Fr. Ben Montecastro, SJ, Sr. Regina Pil, RGS, Fr. Steve Morgan, MM. Yes, there are foreign Susanistas— Maryknoll priests and lay missioners, Jesuit priests, and Mennonites, some of whose stories are included in this anthology.

Add the voice of Joey Ayala. His songs “Wala Nang Tao sa Santa Filomena” and “Bankerohan” are Martial Law protest songs of Davao. “Wala Nang Tao sa Santa Filomena” tells of a depopulated village, mirroring the abandoned settlements in the countryside and the notorious strategic hamlets of Laac in Davao del Norte that mostly affected the Lumads. “Bankerohan” tells of the grenade bombing of Davao’s main public market in 1978, an event also mentioned by several authors. Thus we also learn of the subsequent events—that the funeral procession of bombing victim Karen Guantero was transformed into a 2,000-strong silent protest march in Davao. It was the first openly illegal and subversive act abloom with protest placards that was part of the long process of breaking the terror effect of Martial Law.

Indeed, O Susana! The Untold Stories of Martial Law in Davao is a veritable spider web in which one story thread leads to another, enriching our understanding of events and our appreciation of the people’s efforts, big and small, in fighting the Martial Law regime. Karen’s funeral march had built on earlier small defiant acts in the urban poor communities. In the later years of Martial Law, these protest actions would become bigger, wider, and bolder, finally erupting into the welgang bayan (people’s strikes) that paralyzed not only Davao City, but also the other major urban centers in Mindanao. What were these but rehearsals for the ultimate overthrow of the hated Marcos Dictatorship when the people’s anger reached the boiling point at the EDSA People Power Revolution in 1986.

These stories need to be told and retold and radiated throughout the country because revisionist histories are being written that seek to glorify the Marcos Dictatorship. Already we are hearing naïve views from some younger generations stating that the Marcos Dictatorship did good for the country. These alarming views are abetted no doubt by the fact that the successive elite democratic governments have been utter failures in stemming unbridled government corruption and in solving shameful poverty in our midst. Our deceived youth need to be told, though, that in the first place, Martial Law was responsible for this sorry state of the nation. As Nonoy V. reports, “poverty incidence in 1965 was estimated at 41 percent but increased to 58.9 percent in 1985,” two decades under the rule of Marcos. It is very clear: The Marcos Dictatorship was the biggest failure of all. And never forget the horrendous human rights violations that the Marcos Dictatorship committed to stay in power.

The O Susana book is truly a powerful weapon against deception and forgetting. I am grateful to Karl for the privilege of being involved in this project initiated and pushed through to the end by the Tres Marias. I salute all the Susanistas who took their time out to write their stories to once again tell the truth. This book is their best gift to the country. Never Again! (Permission to reprint this Introduction was granted MindaNews)