Solar panel system powers communities in Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu, South Cotabato. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Solar panel system powers communities in Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu, South Cotabato. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

LAKE SEBU, South Cotabato (MindaNews / 13 November) – For the Manobos in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned here, traveling from their community to the heart of the village is “buwis buhay” – a very risky and very expensive journey — because of the road.

Using a habal-habal (motorcycle), the main mode of transportation to move people and goods in the area, the 14-kilometer stretch from the paved barangay road to Sitio Blit usually takes about two hours. At least twice in that journey, the slippery, muddy and rocky road would allow only a one-way traffic so motorists have to stop and wait for their turn to pass.

To transport goods on that 14-kilometer stretch, habal-habal drivers charge P3 per kilo for corn and P150 per sack of peanuts from Sitio Blit to the center of Barangay Ned. A driver can transport at least five sacks per trip.

To transport people, drivers charge 200 pesos one way.

Located in the mountain, rainfall often pours, ravaging even more the road that cuts off Sitio Blit from the rest of civilization.

A militiaman helps a habal-habal driver transporting corn bring to position his felled motorcycle due to the terribly bad road condition in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu, South Cotabato in September 2022. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

A militiaman helps a habal-habal driver transporting corn bring to position his felled motorcycle due to the terribly bad road condition in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu, South Cotabato in September 2022. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

From Barangay Ned, it would take another three to five hours to reach Koronadal City, the provincial capital of South Cotabato, mostly on paved roads. These are through Lake Sebu town proper, Maitum in Sarangani or Senator Ninoy Aquino in Sultan Kudarat. There’s another shortcut in Sto. Nino, South Cotabato, mainly rough roads, that takes about three hours and mostly taken by motorcycle riders.

For decades, the state of the road has left this community of Indigenous Peoples (IPs, also referred t as Lumads) — the Manobo-Blit — basically neglected, deprived of many essential services from government, including electricity that is widely enjoyed by residents in the lowlands.

In 1971, Sitio Blit gained global prominence after Manuel Elizalde, Jr., head of the Office of the Presidential Assistant on National Minorities or Panamin, announced the discovery of an alleged cave-dwelling Stone Age tribe called “Tasaday,” which several experts later dismissed as a hoax. In 1986, Swiss journalist Oswald Iten, accompanied by the late Joey Lozano, a South Cotabato-based journalist, went to the area to investigate and exposed Elizalde’s claim as a hoax.

The Manobo-Blit community, like their ancestors, rely only on the moon and the stars to light their surroundings at night. However, natural light does not appear regularly as fog often drapes the mountain village.

In 2020, the darkness befalling the 220 households in Sitio Blit ended, thanks to a project called “tala” (star) that lighted their homes — and their lives — using power harnessed from the sun, or solar power.

The Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) spearheaded the project, in partnership with other government agencies.

“Goodbye to dark evenings. It’s a big blessing for us to see clearly during night time,” Lailyn Mae Nobleza, a mother of two grade school students, said in Ilonggo, a language the Manobo Blit are familiar with.

Lailyn Mae Nobleza stands outside her store, which she opens until the evening because of the solar-powered lights. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Lailyn Mae Nobleza stands outside her store, which she opens until the evening because of the solar-powered lights. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Project Tala

Project Tala or TESDA Alay ay Liwanag at Asenso not only brings light to the lives of the Manobo-Blit, it made the residents feel there is, after all, a government that still looks after the welfare of people in last mile communities.

Considered a geographically isolated and disadvantaged area (GIDA), most households in Sitio Blit are impoverished, with the heads enrolled in the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program, the national poverty reduction strategy of the Philippine government.

After TESDA implemented Project Tala, residents incessantly thanked the agency because of the huge changes it brought to their lives.

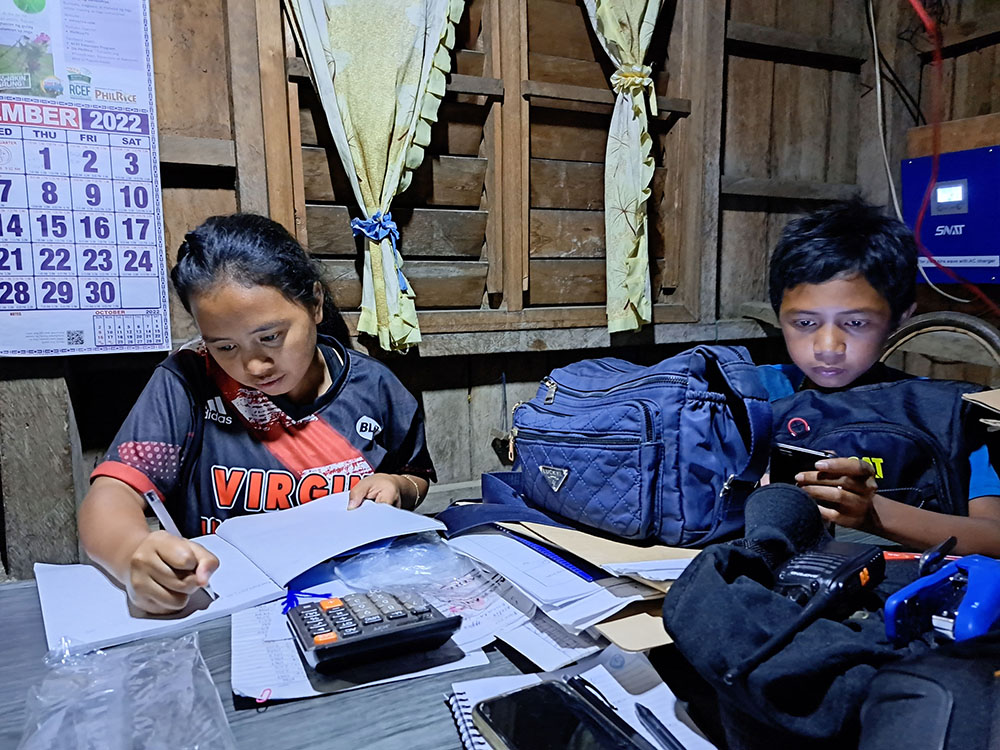

“Our children, now that they have face-to-face classes, can study well deep into the night, well illuminated by light bulbs,” Nobleza said.

Before Project Tala, students in the village could not study at night and residents slept by six or seven o’clock in the evening because it was too dark to see inside the household.

Majority could not afford to buy diesel to fuel the “mitsa” or lamp that could barely illuminate the entire small house with its orange flame. In September, diesel cost around P90 per liter in Ned, The other downside of the diesel-fueled torch is the black smoke that it emits poses risks to human health and the environment.

Diesel is sold at the heart of Barangay Ned, and to go there, a habal-habal passenger has to shell out 200 pesos one way, which is way beyond the financial capacity of the farmers and farmworkers, Nobleza said.

Since using diesel-fired lamps entail additional cost for the family, most households relied on the illumination coming from their stove fed with wood, which is not that bright compared to light-emitting diodes or LED light bulbs.

“Indi tana kami kamurot kung sa dapog lang nga siga amon saligan (We could barely see from the light illuminated by the wood-fed stove),” Nobleza lamented.

Students in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu, South Cotabato study their lessons at night with the help of solar-powered lights. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Students in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu, South Cotabato study their lessons at night with the help of solar-powered lights. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

From “kangitngit” to “kahayag”

Rafael Abrogar II, TESDA-Socsksargen director, said the solar power system they distributed to the households in Barangay Ned costs P7,000 each, consisting of the solar panel, wire, battery and two LED light bulbs.

“One of the main concerns of people in GIDA or isolated areas in the mountains is light during night time. Daghan sa ila nagpuyo sa kangitngit (Most of them have been living in darkness),” he told MindaNews.

These days, residents no longer live in “kangitngit” but in “kahayag” (light).

Out of the 54 sitios in Barangay Ned, 18 have been covered by Project Tala, involving at least 800 households since TESDA rolled out the program in the area in July 2020, Abrogar said.

Aside from Lake Sebu, Project Tala also reached far-flung IP communities in Magpet in North Cotabato, Kalamansig in Sultan Kudarat and Alabel in Sarangani.

Residents were trained on the installation and maintenance to ensure that the solar power system, also called photovoltaic system, can withstand the elements.

“We trained them on how to properly take care of the solar power system to ensure that its use can be maximized,” the official said, adding they taught them the proper positioning of the solar panels to get the most heat from the sun, aside from cleaning the panels often.

Abrogar said the solar panel has a lifespan of at least 20 years while the battery, which serves as power bank, is good for five years.

Solar-powered communal water system, security, anti-isurgency

Aside from the solar power kit distributed to the households, TESDA-12 also installed a photovoltaic system that powered a communal water system in Sitio Blit.

Previously, the Manobo Blit would fetch, take a bath or do laundry at a downstream water source, some 300 meters from the tribal hall of Sitio Blit.

With the power from the sun, an electrical machine pumps water to the tribal hall where faucets and toilets have been installed.

Children take a bath from a faucet, thanks to the solar-powered water pump in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu South Cotabato. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Children take a bath from a faucet, thanks to the solar-powered water pump in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu South Cotabato. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Every morning, the tribal hall teems with children taking a bath, mothers doing their laundry or boys fetching water with the water flowing from the faucets, thanks to the solar-powered water pump.

“The solar-powered water pump is also a big help to the community. Our tribal members no longer have to endure getting water downstream, which is dangerous when raining because of the slippery trail,” said Jared Dudim, the 26-year-old sitio leader.

Residents check the solar-powered water pump in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu South Cotabato. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Residents check the solar-powered water pump in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu South Cotabato. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

A member of the Citizen Armed Forces Geographical Unit, Dudim said the solar lights also provide a sense of security to residents against intruders during night time.

Sitio Blit was once classified as a red zone due to the presence of the New People’s Army. The military referred to the area as “NPA-infested” until it was cleared in recent years. But a detachment under the Philippine Army’s 5th Special Forces “Primus Inter Pares” Battalion has been set up in Sitio Blit to prevent the communist insurgency from taking root again in the area.

“We can see who’s coming to our households with the help of the solar-powered lights. We don’t anymore grope in the dark,” Dudim stressed.

According to Abrogar, the solar power systems they distributed in Sitio Blit were part of the government’s effort to fight the communist insurgency.

Shift to Renewable Energy

Lawyer Pedro Maniego, Jr., senior policy advisor of non-profit Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (ICSC), a Philippine-based international climate and energy policy group advancing climate resilience, said the country must take an aggressive shift to renewable energy (RE) and lessen its dependence on fossil fuels such as coal and diesel to help mitigate the impact of climate change.

In his presentation at the training for the Jaime Espina Klima Correspondents Fellowship, Maniego cited government data showing the country’s power mix dominated by coal plants at 57.2 percent in 2020.

The Philippines imports almost 70 percent of its coal supply in 2019, he added.

Barangay Ned, where Sitio Blit is located, covers a land area of at least 41,000 hectares and is rich in coal deposits. Philippine conglomerate San Miguel Corporation is embarking on a coal mining project there after the Sangguniang Panlalawigan endorsed last December the coal operating contracts earlier granted by the Department of Energy. The Diocese of Marbel has opposed the coal mining project on concerns over the environment and the destruction of farming activities in the lowland if the watershed will be destroyed.

The project is now ongoing.

Maniego stresed the need to shift to RE sources because they are cheap and environmentally-friendly compared to fossil fuels, which emit harmful greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide to the atmosphere.

“The Philippines has abundant renewable energy resources,” he said, adding that fossil fuel resources in the country and elsewhere are limited or not finite.

Renewable energy includes biomass/biofuel, geothermal, solar, hydro, ocean and wind, said Maniego, as he urged the government and private sector stakeholders to accelerate the utilization of RE resources in the country.

“Renewable energy, often referred to as clean energy, comes from natural resources or processes that are constantly replenished,” he explained.

The availability of some RE resources, such as solar or wind, depends on time and weather but they are still largely available in the country all-year round, Maniego said.

A solar panel installed in one of the houses in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu South Cotabato. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

A solar panel installed in one of the houses in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu South Cotabato. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Laws promoting RE

In the Philippines, several laws have been passed to promote the utilization of indigenous and renewable energy resources in power generation to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, which are mostly imported.

These laws include Republic Act (RA) 9136 or the Electric Power Industry Reform Act of 2001, RA 9513 or the Renewable Energy Act of 2008 and RA 11285 or the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Act of 2018.

Jephraim Manansala, ICSC chief data scientist, noted the Mindanao power mix is dominated by coal, providing an oversupply capacity with the addition of coal-fired power plants in the island since 2016.

“This shows poor planning and lack of foresight on their part. As a result, we can see multiple coal plants that are not fully utilized in the (Mindanao) grid, alternating to be operational every few weeks,” he said.

According to the 2019 Power Situation Report of the Department of Energy (DOE), the daily demand in Mindanao peaked at 2,013 megawatts (MW) on 8 May 2019, with an 8.6 percent growth rate from 2018.

The DOE data added the Mindanao grid has an installed capacity of 4,436 MW, dependable capacity of 3,832 MW and available capacity of 2,295 MW.

As of December 31, 2019, the combined installed capacity of coal and oil-based power plants account for 68.2 percent or 3,025 MW, with the former accounting for 47.1 percent share and the latter at 21.1 percent, the DOE reported.

On the other hand, the installed capacity of renewable energy contributes only 31.8 percent, broken down as follows: geothermal at 2.4 percent or 108 MW, hydro at 25.9 percent or 1,147 MW, biomass at 1.6 percent or 73 MW, solar at 1.9 percent or 84 MW, and none for wind, the report stated.

In off-grid GIDAs across the country, Manansala said the source of electricity is mostly generated by diesel-fired plants.

“Amid the rising prices of oil, residential consumers in off-grid GIDA areas are expected to get hurt the most because 90 percent of their electricity comes from diesel-fired power plants,” he added.

The Small Power Utilities Group of the National Power Corp. has been taking the lead in powering up the off-grid areas in the country.

Lighting up lives

Lef Bantal, a kagawad of Barangay Ned who resides in Sitio Blit, is grateful for the solar power that has been lighting up their lives.

She does not dream of their community getting connected to the grid anytime soon, noting the difficulty to reach Sitio Blit because of the terrible road condition.

“These solar panels are better. We do not pay any amount for our electricity consumption,” said Bantal, who bought a spare battery as back-up to the one given by TESDA for emergency use by her family and the other members of her community.

Kagawad Lef Bantal illustrates how to make a “mitsa” or lamp. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Kagawad Lef Bantal illustrates how to make a “mitsa” or lamp. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Aside from lighting their community, allowing students to study at night and improving the community’s economic productivity because they can now work in the evening, the solar power systems paved the way for residents to purchase radio, television and smartphones.

Bantal, who operates a “piso wifi” vendo also powered by solar, said they have been connected to the outside world, despite their remote location, because of the availability of internet, which followed after TESDA distributed to their community free solar power kits.

“We are aware of what’s happening in the lowland, other parts of the Philippines and even abroad because of the wifi, which is also a useful tool for our students for their research,” she said.

Residents in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu, South Cotabato can access the internet because of the wifi vendo powered by the solar power system. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Residents in Sitio Blit, Barangay Ned in Lake Sebu, South Cotabato can access the internet because of the wifi vendo powered by the solar power system. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Not far from the house of Bantal, another piso wifi vendo is operated by Nobleza, who also owns a sari-sari store.

The solar power system enhanced the income of Nobleza, who previously had to close the store when night fell.

“Now we open our store even until 8 o’clock in the evening because of the solar powered lights,” she said. (Bong Sarmiento / MindaNews)

(Reporting for this story was supported by the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (ICSC) under the Jaime Espina Klima Correspondents Fellowship)