KIDAPAWAN CITY (MindaNews / 7 February)—Kidapawan is a place where old names linger, where the tricycle drivers navigate between streets and eras.

Decades after they stopped being exclusive schools, people still call them “Boys” (Notre Dame of Kidapawan) and “Girls” (St Mary’s Academy). The Philippine Constabulary had long been abolished, and yet the town still calls the area of their former quarters “Barracks.”

Long after the abaca industry died the place is still called Berada. The lake has evaporated even in tribal memory, and yet my ancestral barangay is still called Lanao. Go farther into the Greater Kidapawan Area and you will find reference to a long gone anvil (Sayaban), an ancient battlefield (Gubatan), or a legendary zither (Monsouroy). There are of course dozens of places named after long forgotten people, but also after great dogs (Mua-an, Bulatukan, Kisante).

Even the very center of the city, we who grew up in the days before cityhood still call “municipio.”

People once tried to rename some streets, but Datu Ingkal Street refused to give way to Notre Dame Avenue, and Pendatun refused to give way to Antonino Street.

And yet those attempts to rename the streets have been telling: that despite the strength of what the National Historical Commission of the Philippines calls “sanctity of usage,” Kidapawan history is also rife with instances when place names—specially indigenous ones—have been replaced with new ones.

Granted, not all such changes are necessarily negative—what used to be called the Kidapawan-Ilomavis Tourists Road, for example, had come to be renamed “Datu Joseph Guabong Sibug Avenue” (after the former Vice Mayor and IP Rights leader who once lived on the street. The renaming was a triumph of the local and the specific over the national or the generic.

But such triumphs are few and far between. And in the case of indigenous place names—the names given by the Monuvu, who have lived in Kidapawan since time immemorial—removal and replacement with foreign names assumes a colonial dimension, one of cultural displacement and hegemony.

In some cases, the change is brought about by the dominant population’s failure to pronounce the unique Monuvu phonology—“Soyavan” became “Sayaban” because the Bisaya cannot pronounce the Monuvu /v/, and all places or landmarks with long vowels and consonants (“Laapan,” “Motinggow”) had to adjust to the Bisaya phonology.

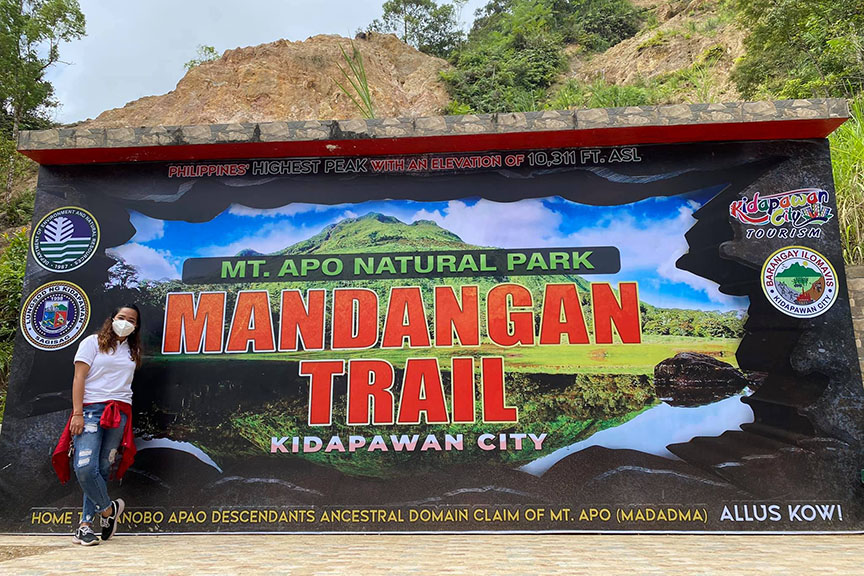

In at least one prominent case, that of the Mondaangan trail, the replacement was from a more prominent indigenous culture. The trail used to be called “Mandarangan,” but this is a word in the language of the Tagabawa, a culture on the other side of the mountain. The Monuvu (on whose ancestral domain the trail fell) used the word “Mondaangan,” the name of the Onitu (spirit) associated with the Bohani (warriors) and the trails they stalk.

The Monuvu have been able to assert themselves over the top tourist destination in this case, with formal signage now using “Mondaangan,” but there is still lingering resistance among hikers who do not bother understanding the change.

In other cases, the indigenous name is retained, but some fabricated folklore is given to explain its origin.

Most blatant example among all perhaps is the name of Kidapawan itself, with the local government publishing as official explanation at least three made up etymologies that do not make sense in the Monuvu language it is claimed to have come from (part of my job has been to correct that).

A more subtle example has been Linow to Saarong, the body of water more popularly known as Lake Venado. Although the incongruously Spanish name (when the Spaniards never set foot anywhere near it) is basically just a translation of the Monuvu name (both “Saarong” and “Venado” mean deer), the proposed explanation is a settler—or rather a hiker—imposition. The lake, as official sources go, is said to be shaped like a deer, but the Monuvu do not see it this way. Instead, the lake is associated with deer not only because deer once gathered around it to drink water (and it therefore used to be a great hunting location), its surroundings are associated with a mystical white deer, contact with which is said to bring Tuwadnus—the transporting of mortals into the realm of the spirits.

Usually, however, a place’s ancient name is simply replaced with another one completely different or wholly inappropriate to the place. “Linow to Diwata” (lake of spirits) had been renamed “Lake Jordan” and a portion of the range called “Mivuwow” had been renamed “Mt. Zion” by a settler Moncadista leader named Maximo Gubiernas. “Linow to Mivuwow” (the lake of Mivuwow) has been renamed “Lake MACADAC” by the Mt. Apo Climbers Association of Davao and Cotabato.

These are just some of the 80 or so names documented by the Manobo Apao Descendants Ancestral Domain of Mt. Apo (MADADMA) for the Patow to Livuta (indigenous landmarks) within its ancestral domain in the barangays of Ilomavis and Balabag and the neighboring barangay of Kawayan in Magpet. These villages, peaks, rivers, lakes, and streams have been called by these names for generations, but many are no longer used, replaced by foreign names that have little to do with the place’s history.

Elsewhere, acronyms imposed by settlers have displaced now archaic names: “Onica” (for Occidental Negros, Iloilo, Capiz, Antique) has replaced “Malamote.” “Ilomavis” (Ilocano, Manobo, Bisaya) has replaced Motingngow (meaning “pure”), and “Sumbac” (Sumin, Manobo, Bagobo, Christian) has replaced “Limokon” (a sacred bird).

The displacement of names does not only mean what the place or landmark is called has changed, it means the entire histories surrounding these places are erased.

And it is not only the indigenous which has suffered displacement—ultimately all things local are at the mercy of the national. Of Kidapawan’s 17 mayors, none have been the namesake of its streets. In fact there are only three streets named after local officials: Datu Ingkal Street (named after Datu Ingkal Ugok, who had been the first colonial official), Datu Joseph Sibug Venue, and Fabian Labastida Street (the former councilor and war veteran who once lived on the street).

One street has been named “Quimco Street” after another former councilor, but that name (given in 1986 by a council resolution) is still struggling against an older name, “Tamesis” (given by an older 1951 resolution). This is one of many such conflicts in Kidapawan’s street naming, as the two extant street naming resolutions come into conflict with one another and with sanctity of use.

I had made several unsuccessful attempts to initiate the renaming of Kidapawan’s streets to remedy this and many other anomalies. I had drafted a City Council resolution fixing conflicting street names, balancing the sanctity of use with the need to champion the local (specially in streets that had once been home to past officials) and the indigenous (the draft would have been the first piece of legislation in the world to name mountain trails, giving them the names of the tribal leaders who made them). The draft had been submitted to two councilors, but it never even saw first reading.

But the work decluttering Kidapawan’s toponymy continues, and where the formal, legal arena may prove difficult to fight, perhaps the field of cultural transformation would offer better ways forward.

Because if one can change a place’s name detrimentally, one can also bring about change for the better.

(MindaViews is the opinion section of MindaNews. Karlo Antonio G. David has been writing the history of Kidapawan City for the past thirteen years. He has documented seven previously unrecorded civilian massacres, the lives of many local historical figures, and the details of dozens of forgotten historical incidents in Kidapawan. He was invested by the Obo Monuvu of Kidapawan as “Datu Pontivug,” with the Gaa (traditional epithet) of “Piyak nod Pobpohangon nod Kotuwig don od Ukaa” (Hatchling with a large Cockscomb, Already Gifted at Crowing). The Don Carlos Palanca and Nick Joaquin Literary Awardee has seen print in Mindanao, Cebu, Dumaguete, Manila, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Singapore, and Tokyo. His first collection of short stories, “Proclivities: Stories from Kidapawan,” came out in 2022.)

=========================

On this section of Moppiyon Kahi diid Patoy, we remember important dates and incidents that took place in Kidapawan history.

1 February 1982 – Attempts were made by the municipal government of Mayor Augusto Gana to convert all the puroks of Kidapawan’s poblacion into barangays. The municipal council session of that date records Gana proposing the creation of 10 new barangays out of the poblacion area.

The plan never materialized, but it illustrated the Gana policy of creating more barangays to receive aid from the Marcos government, explaining Kidapawan’s relatively high number of barangays

4 February 1956 – the municipal council passes Resolution No. 59 of that year, formally allowing barrios to form their barrio governments. This is the beginning of barangay government in Kidapawan

5 February 1963 – Dr. Emma Bagtas Gadi takes over as mayor of Kidapawan after winning an electoral dispute against Dr. Alberto Madriguera. Gadi would be the first Kidapawan mayor to win an electoral dispute, and to date has been the only woman to sit as Kidapawan mayor. Her first stint as mayor lasted less than a year.