KIDAPAWAN CITY (MindaNews / 30 January) — “Kidapawan history begins with Monuvu history.”

This was my assertion when I had a dialogue early this month with the Council of Elders of the Manobo Apao Descendants Ancestral Domain of Mt Apo (MADADMA), the holders of the Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title in the upland barangays of Kidapawan.

We were in talks about proposed monuments honoring the semi-legendary Apao, the founding ancestor of MADADMA’s clans. Apao was, according to tribal memory, the first man to climb Mt. Apo, which foothills his descendants today call their ancestral domain. He had given the mountain its ancient name – Lumut to Sondawa – and he had discovered and named many other landmarks in the Kidapawan uplands.

I lamented the marginal place to which very important Monuvu figures like Apao have been relegated in the writing of Kidapawan’s history, and part of my work as city historian has been to slowly help undo that. These proposed monuments are but part of that work. (I will be writing articles dedicated to Apao and to this project later).

A few years ago Bo-i Era Umpan Colmo Espana successfully campaigned to have a line in the Kidapawan hymn changed. The line now reads, “mga katutubo ang nagpasimula,” an explicit insistence that Kidapawan was founded by the Monuvu.

The years I have pored through archival documents and gathered oral history from key informants only confirms what Bo-i Era has asserted. It is not simply enough to say that the Monuvu were the first inhabitants of Kidapawan, Kidapawan came into existence as an entity – and as a community – because of the Monuvu.

Aside from discovering and naming landmarks, Apao was also one of the founders of the indigenous political structures in the Greater Kidapawan Area, Kidapawan’s earliest forms of government (in areas like MADADMA’s ancestral domain, these structures continue to exist). With the coming of colonial government, many of these structures seamlessly transitioned into formal barrio governments (I have observed that areas where the transition has not been seamless – such as in Ilomavis, where much of MADADMA’s ancestral domain is included – tensions often arise).

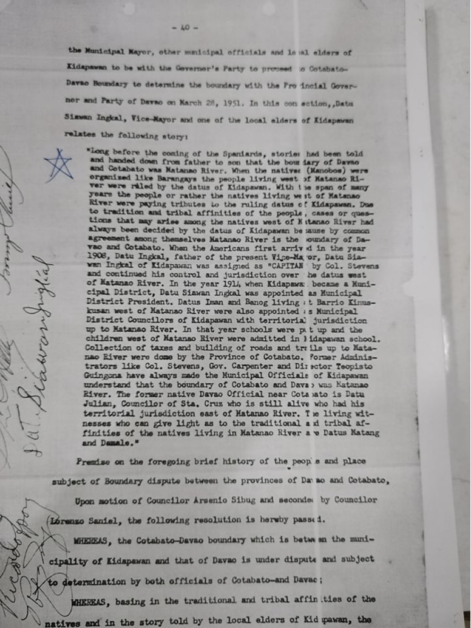

This transition became possible because Kidapawan itself started as one large indigenous political structure, the sphere of influence of the Datus Ingkal Ugok and his son Siawan Ingkal. When the Americans organized Kidapawan into a Municipal District in 1914, they appointed Datu Siawan as Municipal District President. He in turn appointed another Monuvu, Datu Amag Madut of Mua-an, as his Vice President, and formed a Municipal District Council that, for much of its history, was dominated by tribal leaders.

From its founding until well into the Second World War, the Municipal District of Kidapawan was governed by customary law – Pooviyan woy Gontangan – which recognized the Toka-an (localized way of doing things) of each area and its datus. Rulings and penalties were made following customary law, which was arbitrated by the datu and which was enforced with the help of skilled warriors called the Bohani, who under Datu Siawan had been made members of Kidapawan’s earliest police force (their first Chief of Police, Datu Cone Icdang, was a particularly celebrated Bohani).

These facts – that its founding officials were Monuvu and that it was originally governed with Monuvu law – allows me to speculate that Kidapawan was originally organized as a Monuvu entity within the colonial American government (this would be consistent with America’s policy during that time, as it organized tribal wards along ethnic lines).

If such a paradigm would be assumed, that would mean the de jure extent of the Municipal District of Kidapawan would have originally encompassed all territories that traditionally fall under the ancestral domain of the Monuvu-speaking people.

To the southeast, Datu Siawan is recorded in the Municipal Council sessions as saying that Kidapawan’s border was the Matanao River – that would mean even a portion of what is today Baranggay Marber in Bansalan would have once been part of Kidapawan. But the exact extent of Kidapawan in other directions has not been documented. If (we) were to follow the Monuvu borders, one could argue that areas of Davao City’s Calinan, Baguio, and Marilog areas may have originally been intended to be part of Kidapawan as well, as these spaces have Obo Monuvu populations.

The municipal district however did not become a Monuvu enclave, because the Monuvu have historically always been accommodating of other cultures, exogamy being the norm. It is to the extant Monuvu society that Settlers and immigrant Moros – who started trickling in informally starting in the 1910s – were slowly integrated. Settlers were welcomed as neighbours, many of them being given land (or granted it after barter). Some – such as the early Kidapawan politicians Arsenio Sibug and Lino Madrid – went ahead and married Monuvu women. The story of Kidapawan’s oldest Settler and Moro families all begin with the Monuvu welcoming them into an already pre-existing community.

A shared humanity had been the emphasis of this accommodation, but the darker side to it has been the pervasive practice within the introduced colonial institutions to dismiss the indigenous as inferior – Monuvu identity ironically and tragically became a liability, and for some generations the Monuvu were punished economically, socially, and politically for following their culture, assimilation into the increasingly dominating Filipinized colonial identity incentivized with success.

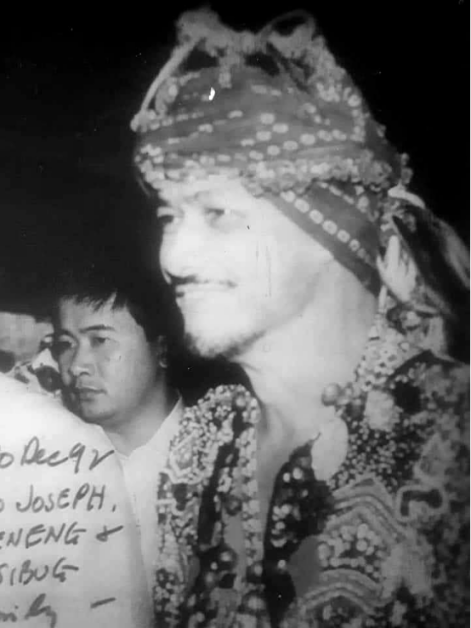

The gradual marginalization became such that by the time the IP rights leader Datu Joseph Sibug started publicly asserting his Monuvu identity in the 1970s while he sat as municipal official, the tribal primacy that his uncle Datu Siawan Ingkal once enjoyed was long gone, and the agenda had become one of inclusivity and the undoing of marginalization and institutionalized discrimination.

The struggle towards that inclusivity is still ongoing, although Kidapawan has seen much progress since Datu Joseph’s days as Vice Mayor. It has formed official institutions in the municipal and city government championing IP rights, it has had an IP congresswoman and governor, Nancy Catamco, and after decades without representation it now once again has IPs in its City Council. Recently it just passed its IP Code, which safeguards IPs against the discrimination and exploitation that have suffered for decades.

Much work remains to be done on the cultural side. Datu Joseph (and his contemporary in Davao, the mayor Elias Lopez) championed the celebration of the indigenous as the “original Filipino,” and since the ’70s this has resulted in the cultural festivals, the indigenous cultures taking center stage in public events. That was an important development, but we have since outgrown it, and the demand now is to mainstream indigenous identity into daily lives, making it not only exotic curiosities to showcase, but sources of human wisdom with which we enrich our lives.

In the field of literature and history at least, I do what I can, processing Itulon (oral history) in the same way I would process political and administrative history, drawing philosophical and sociological conclusions from incidents that the Monuvu have been able to recall collectively and transmit to posterity.

[MindaViews is the opinion section of MindaNews. Karlo Antonio G. David has been writing the history of Kidapawan City for the past thirteen years. He has documented seven previously unrecorded civilian massacres, the lives of many local historical figures, and the details of dozens of forgotten historical incidents in Kidapawan. He was invested by the Obo Monuvu of Kidapawan as “Datu Pontivug,” with the Gaa (traditional epithet) of “Piyak nod Pobpohangon nod Kotuwig don od Ukaa” (Hatchling with a large Cockscomb, Already Gifted at Crowing). The Don Carlos Palanca and Nick Joaquin Literary Awardee has seen print in Mindanao, Cebu, Dumaguete, Manila, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Singapore, and Tokyo. His first collection of short stories, “Proclivities: Stories from Kidapawan,” came out in 2022.]

=========================

On this section of Moppiyon Kahi diid Patoy, we remember important dates and incidents that took place in Kidapawan history.

4 January 1988 – the Guangan, Makilala Retaliation – several houses were burned by the Tadtad (one of the violent militias, also considered a cult, that was tapped by the military in the war against communists during the first Marcos and first Aquino governments) in retaliation for an earlier encounter that saw military casualties

7 January 1973 – A public rally was organized in Kidapawan’s Plaza to launch the draft 1973 Constitution. Then mayor Augusto Gana publicly endorsed the draft.

15 January 1952 – The Municipal Council made Kidapawan’s first attempt to name its streets when it passed Resolution No. 21 of that year. The resolution names 32 streets in the Poblacion and chooses a combination of local and national figures (such as Judge Dayao and Jose Rizal streets) as namesakes for the streets. The names are mostly still used today.

16 January 1954 – Mayor Alfonso Angeles Sr. is recorded giving the earliest public reference to a bid for Kidapawan cityhood. He expressed the possibility that the municipalities of Kidapawan and Kabacan would merge to become Kidapawan City

17 January 1975 – the province turned over the management of Kalibongan, the Provincial Festival, to Kidapawan. The festival’s main proponent, Datu Joseph Sibug, was Kidapawan Vice Mayor that year. Kidapawan would struggle to manage the cultural festival, and it would later give it up, its organizers being compelled to take it to Davao.

23 January 1993 – President Fidel Ramos granted the Philippine National Oil Corporation the right to set up geothermal operations in Barangay Ilomavis and Balabag.

23 January 1961 – Bai Matabay Plang appears before the Kidapawan Municipal Council to pitch the creation of a Children’s Foundation Village in Arakan. The council adopted a resolution to endorse the village’s establishment to Congress (the village would be created, and would today be part of the Cotabato Foundation College of Science and Technology in Arakan).

24 January 1963 – Vice Mayor Andres Villasencio was appointed acting mayor by Alberto Madriguera, who had lost an electoral protest against Dr. Emma B. Gadi. Villasencio himself would resign shortly after Gadi took over. This is the first known electoral dispute in Kidapawan history. The other officials elected in 1959 remained in office.

24 January 1988 – The San Isidro Incident: two members of Tadtad were killed while two others were seriously injured in San Isidro when the New People’s Army ambushed them.

27 January 1983 – Geronimo Ajero, former barangay captain of Mateo, was murdered in his own home with his son Fernando. Four armed men were reported to have come to their home and killed them, and by the time theirs relatives arrived (according to surviving relatives of the Ajeros), pigs had already gathered to sniff their bloody remains. The councilors do not speculate about who was behind the murders, but the Ajero family put the blame squarely on the NPA.

30 January 1988 – Saturnino Goc-ong, a deacon in the parish Makilala, was killed by Tadtad fanatics.