KIDAPAWAN CITY (MindaNews / 26 December) – December 26, 1976 may well be the darkest day in Kidapawan history.

In two separate locations within Kidapawan’s westernmost barangay of Patadon, elements of the Philippine Constabulary and the Ilaga (a paramilitary group armed by the Marcos government) gunned down dozens of civilians, killing at least ten people.

One of the massacres happened in Sitio Pagagao, in what was then a small hamlet of refugees displaced from a recent flooding in Pagalungan. They had moved to the sitio temporarily as they had relatives there.

The armed man arrived when they saw a boy wearing a Taqiyah (Patadon is the only predominantly Muslim barangay in Kidapawan). They alighted, and strafed the crowd.

Dozens were injured. Of the many who were killed, only five names survived to memory: Oki Kadil (a young boy), Otin Kadil (Oki’s brother), Maimona Kala Kadil (an elderly woman), Maslaba Bai Kamad and Ramon Kamad, who was 12 years old.

There is no recorded account of the Pagagao Massacre but there is oral memory of what happened nearly 50 years ago.

A Moro elder in the nearby barangay of Amas, the late Diatugan Labog, gave me the first account of it in 2018, before he took me to see Salamen Kadil, a relative of those killed during the incident. With Labog and Kadil, and later with a survivor, Rowida Pagagao Sinambong, we were able to piece together what happened.

Then-Kagawad Haydeelyn Demalen Manalundong (seated), interviewing Rowida Pagagao Sinambong (standing), survivor of the Pagagao Massacre

Instrumental to this documentation was the Moro member of the Kidapawan City History and Heritage Research Team, then-Kagawad Haydeelyn Demalen Manalundong.

It was Manalundong who uncovered the other massacre, which took place on the same day and just around the same time as the strafing in Sitio Pagagao.

This time, the killings happened in Patadon Centro or what was then the center of the barangay. A different group of PC and militiamen arrived and ordered a group of civilians in the area to lead them to the barangay captain.

But on the way the armed men opened fire, hitting not only the people ordered to lead them but the civilians living in the nearby houses as well.

Seven people are known to have died: Kalumenga Agad, Amelol Ubal, Bakwit Aplal, Bawkingking Ayunan, Suweda Pedtamanan, Esmael Awal and Datu Punso who was only four years old.

The primary source for this is one of the civilians forced to lead the way, Akob Awal, brother and grandson of the dead. Akob survived by hiding until the armed men left. He was one of many who managed to survive. Like the Pagagao Massacre, the incident has never been recorded until Ma’am Haydee documented it.

The Patadon Centro Massacre apparently changed the barangay’s landscape. After the incident, the people living around the area fled, and today what used to be the barangay center is now remote and sparsely populated. Only the reminders of its position as center remain: the grave of Datu Patadon Tungao (after whom the barangay is named), and the word ‘centro’ in the sitio’s name.

In both massacres, the dead were buried in a mass grave. The Pagagao mass grave could hardly be discerned, but the Patadon Centro mass grave is a simple foxhole, the soil inside forming a soft mound.

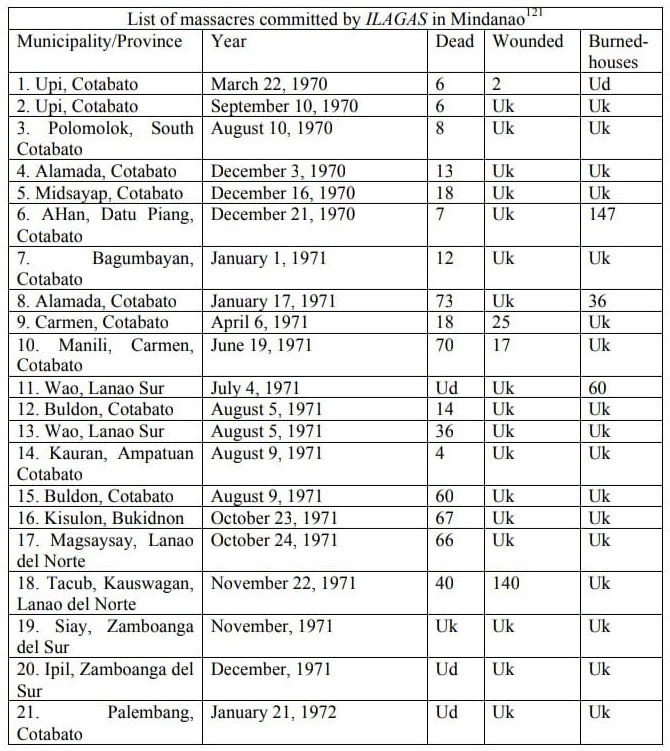

The Pagagao and Patadon Centro massacres were just two of a total of seven atrocities committed by the then Marcos government and the militia it armed against the Moro civilians of Kidapawan.

This does not include the massacres we ended up recording in other parts of the Greater Kidapawan Area – the Bulodan Massacre in Manobuan, Matalam perhaps being most gruesome, with the breasts of the teenage girls sliced off after they were killed.

The recording has been part of our effort to expand the seminal list of atrocities in Mindanao compiled by Salah Jubair in his 1999 book Bangsamoro: A Nation under Endless Tyranny.

Why did it happen? From the accounts we gathered (and consistently with all such atrocities), it was indiscriminate. Survivors said the perpetrators targeted anyone they identified as Muslim – including children who spoke Maguindanaon

The historical backdrop that led to this, however, is more complicated: it was the height of what came to be known in Kidapawan as “Christian-Muslim conflict,” the armed violence that erupted in the wake of the Moro insurgency triggered by Udtog Matalam’s Muslim Independence Movement.

In Kidapawan, this period (1974-1978), communal violence was prevalent between the armed “Ilaga” (literally rat) identified with Christians and the armed “Blackshirts” identified with Muslims. Even Christian civilians played a part by perpetuating bigotry: an association petitioned to have all streets named after Muslims in Kidapawan renamed.

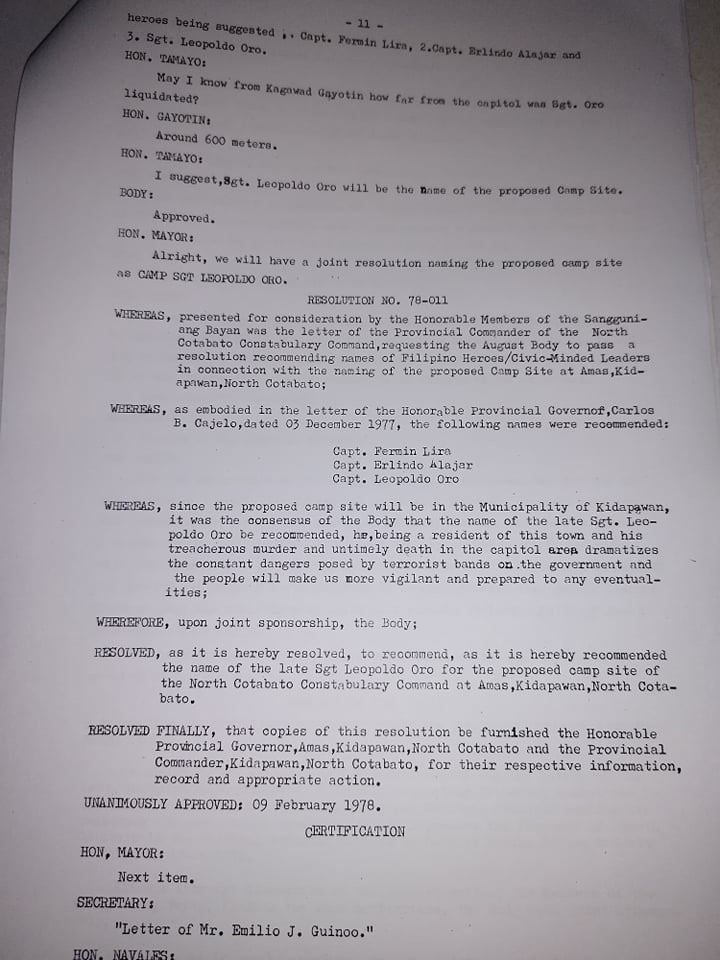

The “Blackshirts” had penetrated the Greater Kidapawan Area, and they are believed to have been behind the ambush of Sgt. Leopoldo Oro, the secretary of then Cotabato Governor Carlos Cajelo. Oro had been killed just 600 meters from the provincial capitol grounds in Amas, and from the accounts of the Moro civilians still living in Amas and Patadon, it infuriated the PC and their fellow armed men.

It was, according to the survivors, out of this climate of resentment resulting from the death of Oro that the Pagagao and Patadon Centro massacres happened on the same day.

Oro’s date of death is not clear but residents of Patadon who live near the massacre sites – survivors and relatives of the victims – are certain it happened before December 26.

That the massacres happened a day after Christmas has led the community to speculate that this may have been an after-party vendetta spree, the armed men made reckless with their inebriation.

In the end no case was filed against any of the armed men behind the shooting, and the dead never got justice. They got away with it.

And Kidapawan today barely remembers the darkest day in its history, when several of its innocent, law-abiding civilians were gunned down apparently for the simple reason that they were Muslim. The same inability to see the humanity in those who were killed is the same apathy which today continues to kill their memories – those who insist on forgetting in the name of ‘moving on’ are complicit to the atrocity whether they are aware of it or not, because it is in by their insistence to forget that those who would commit such atrocities in future will continue to get away with it.

It is incumbent upon us who live today to keep the memories of the dead alive, because these deaths will only really be senseless if they are forgotten, denied of any future reflection. Lessons may well remain buried in the mass graves, waiting for future generations to germinate and bear fruit.

And so today, we remember.

(MindaViews is the opinion section of MindaNews. Karlo Antonio G. David has been writing the history of Kidapawan City for the past thirteen years. He has documented seven previously unrecorded civilian massacres, the lives of many local historical figures, and the details of dozens of forgotten historical incidents in Kidapawan. He was invested by the Obo Monuvu of Kidapawan as “Datu Pontivug,” with the Gaa (traditional epithet) of “Piyak nod Pobpohangon nod Kotuwig don od Ukaa” (Hatchling with a large Cockscomb, Already Gifted at Crowing). The Don Carlos Palanca and Nick Joaquin Literary Awardee has seen print in Mindanao, Cebu, Dumaguete, Manila, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Singapore, and Tokyo. His first collection of short stories, “Proclivities: Stories from Kidapawan,” came out in 2022.)