BOOK REVIEW

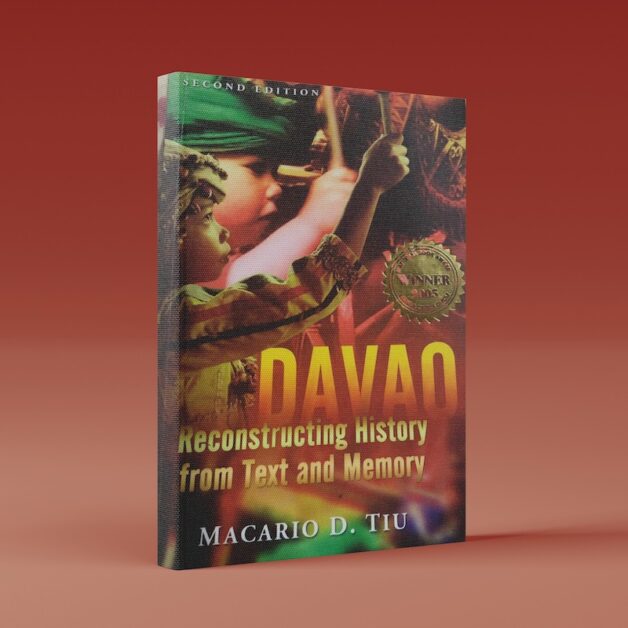

Tiu, Macario D. 2021. DAVAO Reconstructing History from Text and Memory

Davao City: Ateneo de Davao University, 571 pages.

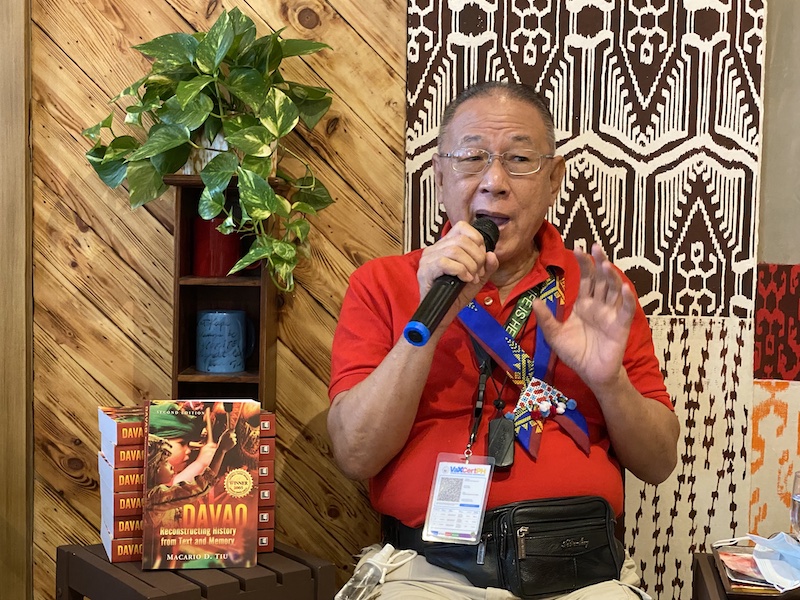

ILIGAN CITY (MindaNews / 31 December) — Writing the histories of Mindanao is once more given a boost in the publication of Macario D. Tiu’s Davao Reconstructing History from Text and Memory. 2021. Davao City: Ateneo de Davao University.

Davao City came to national scrutiny when one of her sons became the 16th President of the Philippines, Rodrigo Roa Duterte and currently, daughter Inday Sara, as Vice President.

Interest in the city and the entire province remains and what better way of knowing more about this region than by reading Mac Tiu’s first edition, recipient of the 2005 National Book Award by the Manila Critics Circle, and the second edition of his Davao History and after one more book, Davao History by Ernesto Corcino.

In a way, Mac Tiu’s second edition of the history of Davao inspires the writing of local history to foreshadow a future encyclopedic Philippine history that will be diverse and colorful, and ideally, by several Filipino historians from different regions.

There is no doubt that a prize-winning writer like Mac Tiu, knowing full well how a narrative unravels, has put to good use narrative techniques in particular, thematic patterns, plot twists, characterizations, and of predestinies that Davao would become in the future.

Literature is a cousin of history. Reading the book using many approaches and applying, among others, the principles of New Historicism particularly in Chapter 5 – the Myths and Legends of Davao – was rewarding, alongside the textuality and historicity of texts, the discourses on cultural identities and of power relations between the colonized and colonizers.

Literature teachers on the one hand, can learn from New Historicism when reading Chapter 5 – the Myths and Legends of Davao. Several ideas from Althusser, Derrida, Foucault, Marxism and New Humanism brought about New Historicism in the 1980s and were put forward by Stephen Greenblatt.

This approach studies literary texts side by side with milieu – the political, social, and cultural situations when the texts were written and the process by which these literary texts came about.

But the entire contribution of Mac Tiu’s second edition of Davao History is practically from his own experiences as a scholar, writer, and as historian.

Among the best practices of this scholarly work is his own sleuthing for a lead that would get him to an original source, be it the descendants of Davao’s heroes or of primary texts and through interviews and, as one keen on the study of folklore, including oral histories from Davao’s various ethnic communities in Chapter 5.

These oral histories and traditions are part in reconstructing the past composed of memories that bear kernels of truth in the absence of solid structures, documents, and other tangible evidence of a distant past and as victims of colonization, foreign cultures supplanting whatever the country’s early inhabitants had.

As artifacts these oral narratives represent Davao’s mythic past – a past that must have been retold through many generations, but such is orality.

The point is that these myths and legends have been recorded and form part of a history book. It should be of interest to scholars to study these finds too.

Mac Tiu has indeed done much service to the nation through his engaging telling of the story of Davao’s ethnic diversity and the connections that have been nurtured to take its significant place in Davao’s development – a thriving metropolis in this southern part of the country.

In his Preface, Dr. Patricio “Jojo” Abinales said that the value of this book “lies in reminding everyone of the various connections that Davao has had with other parts of the islands”.

We agree. Mac’s ability to show these connections of communities as diverse culturally and linguistically through his use of various approaches in obtaining information such as getting hold of tarsilas and other non-Western primary documents, Abinales says is “evidence on Davao’s keeping ties with the Muslim Zones and the hinterland communities prove that ties have not been severed” even during the colonial periods.

It is amazing therefore how such diversity has grown with the coming of settlers that should make Davao a place of peaceful co-existence among tribes and settlers. Perhaps, it is relevant here to say that a national language will come from this melting pot of disparate tongues and rhythms.

Mac Tiu explores likewise the origins and differences in the use of certain terms like “Lumad”, “Moro” and “Settler” as well but these are only part of a bigger picture in presenting Davao’s complex history in five Chapters.

In Chapter 2, Mac Tiu puts a premium on the peopling of Davao and gives us an insight into migrations of groups from other parts of Mindanao and beyond, and how its economy grew and contributed to the country.

An exciting section shows how new names have surfaced of Davao’s lumad heroes to heroes during the infamous Martial law years.

And we learn of descendants of Datu Bago, whose name has taken a backseat to Oyanguren, with that obscure street named after him hidden in Davao’s Bangkerohan. But we learned that the Davao City Council has declared Datu Bago a hero but, except for an award in his name during the Kadayawan festivities, more effort is needed for him to be known throughout Mindanao.

The Tribes of Davao on Chapter 4 is instructive and should be a guide to textbook writers who write about Mindanao and her peoples with superficial research, much less a glimpse of the island’s map and without knowledge of the diversity of Mindanao to put an end to these labels: “Muslim Mindanao”, “Muslim Dance”, “Muslim Language”.

In other words, there is no substitute for a homegrown historian such as Mac Tiu to get precise information of names and locations of places where the tribes are found in Davao and the photos, showing the reader natives from these respective tribes is no mean feat, if we understand how referrals, negotiations, and convincing sources to open-up, or to ask them permission to use photos and information — a tedious process.

Local historians should be inspired to write about their own localities as well because it is the only way Filipinos can have a rounder view of themselves as a people given our country’s geographical make-up, fractiousness and, well, ignorance of each other.

(This review was first posted on the Facebook page of the Mindanao Creative & Cultural Workers Group, Inc. MindaNews was granted permission to publish this)