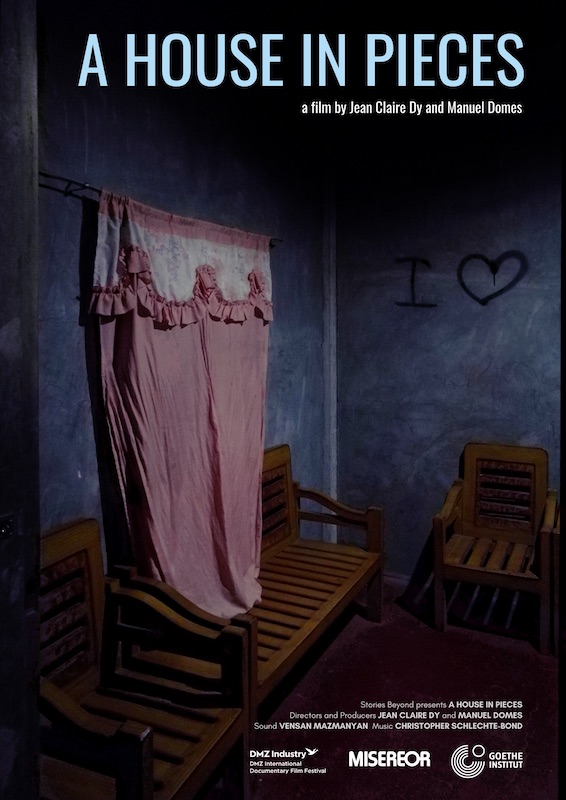

QUEZON CITY (MindaNews / 13 June) — At the center of Jean Claire Dy and Manuel Domes’s heartbreaking documentary, A House in Pieces, is the idea of home expressed in different but all of them painful ways — as ruins of a city in the present, spaces of residence abandoned; as a longed-for past, cradling one’s memories, that is yet within arm’s length but now irretrievably lost; and as defiant hope for a future shadowed by uncertainty.

The idea is signified figuratively in the film’s opening sequence. We hear chanting and read lines from Darangen, the fourteenth-century Maranao epic, over an image of a minaret peeking behind the mist. The evocative epigraph speaks of a deep Islamic history dating back hundreds of years before Spanish colonization, a venerable past that must always be returned to but cannot be repeated even while it remains ever-present in the Muslims’ new stories. The sequence is a dreamy image teased by the mundane presence of power lines and steel frames jutting in the foreground, reminding us of where we are.

Then we meet Yusop speaking about his homing pigeons that can be domesticated even in unseemly places if, he says, “they are treated well.” Interwoven by editing with images of the wreckage, we behold the birds as they fly freely over the ruins of Marawi, a far cry from the enchanting cityscape that it once was.

Even I, who has only visited Marawi once, in 2015, and realizing that that visit can never happen again, can feel a sense of loss and a pang of sorrow as I behold the structures reduced to rubbles, buildings riddled with bullet-holes. How much more the people whose lives were uprooted and who have not been allowed to come home four years after the war?

This sense of witnessing phantom houses summoned so hauntingly in A House in Pieces is what sets Dy and Domes’s film apart from broadcast documentaries, which, though informative, tend to revel in the televisuality of the devastation, and though featuring first-hand accounts of soldiers and civilians, tend to be businesslike and to make their subjects appear like helpless sufferers.

Such documentaries may be helpful in analyzing the cold facts of the war and its aftermath. However, their inclination to amplify the sense of Marawi’s distance and its people’s victimhood is precisely the tendency that has kept non-Muslim Filipinos from truly understanding and empathizing with their Muslim brethren. A House in Pieces humanizes and dignifies their subjects, showing their perseverance, their labor of making meaning out of the tragedy, and their profound understanding of their situation.

The filmmakers surmount the ill tendencies of conventional broadcast documentaries because of their double consciousness as insiders and outsiders. Dy is a Mindanaon writer and filmmaker who has worked in but has also lived away from Mindanao, and Domes is a German artist and peace consultant who has done work in Mindanao for international NGOs.

Apart from their subject positions, the years they invested in shooting the documentary, which broadcast journalists, especially foreign ones, do not have the luxury of having, allowed them to witness the experiences of their subjects on the ground in all their messy dailiness. In place of sit-down interviews, the filmmakers entered into lengthy conversations with Maranaos, in the process capturing their candid thoughts and unguarded moments. The filmmakers’ relatively long time of production is emblematized by the unhurried pace of the documentary and the impressionistic visual rendering of the surroundings, the human-made disaster enveloped by nature’s indiscriminate beauty.

The subjects whose lives the filmmakers feature illustrate how suffering is variously lived out. The couple Yusop and Farhanna, who were relatively marginalized before the siege, found themselves saved for being situated in the periphery of the city center, which turned out to be ground zero of the urban warfare. From a distance, they could hear the carnage; they were gripped with fear, but they survived and are now returning home. In their seemingly provisional existence are nurtured spontaneous lullabies of grief that Farhanna sings to her child as she stares sorrowfully in the distance and oral tales of the war and its environs, its dogs, and snakes, and tanks, and jets overhead that only those near enough to witness but far enough not to get hit could vividly retell.

Nancy, who lived a more comfortable life before the siege, has lost much, and we feel her loss as the filmmakers accompany her as she revisits the concrete edifice that she used to call home. Now she lives more modestly in an evacuation unit, without the means to make her living. More than the loss of property, it is being separated from her family while her children eke out a living in Manila for all of them to survive, which hurts her the most. Alone, all sad love songs become her own heartbreak songs.

The faceless driver, Abdul, seems unsettled, chauffeuring the filmmakers around Marawi. Like an eschatologist, he philosophizes and offers reasons why such a tragedy befell the Maranaos. His words do not constitute a social scientific treatise, but they are a revelation of habits of thinking and homegrown turns of thought.

Perhaps the most terrifying subject is the fatalist Maute fighter, soft-spoken and thin-framed Usman, whose son he proudly lost to martyrdom. He is remorseless because his cause is holy. He declares with confidence that, just as sure as he and his son had learned to carry guns in their youth and waged war together, so will the fighters in hiding rise again.

All of them speak of home—of destroyed domiciles; families one must sacrifice for; communities displaced, and communities formed around evacuation centers; kinfolk ruing how their fellow Maranaos could hurt them so; and the universal congregation that radical ideologues believe surpasses one’s blood.

All of them speak of home—of destroyed domiciles; families one must sacrifice for; communities displaced, and communities formed around evacuation centers; kinfolk ruing how their fellow Maranaos could hurt them so; and the universal congregation that radical ideologues believe surpasses one’s blood.

It is often mentioned—because it is true—that before the siege, Marawi was a vibrant Islamic city. A House in Pieces pictures limbo in its place, a powerful metaphor for the situation of the Maranaos. Their suspended existence corresponds to Marawi’s negative form of islandness—separated, isolated, neglected—a postponed existence complicated by the jihadists’ genuine sense of holiness, of being set apart.

Thus, whereas this urban island has been positively identified as belonging to a host of multi-cultures, especially in benign forms of cultural celebrations, the seduction of extremism for a disenchanted section of the populace negatively identifies the space as being externally alienated—precisely the pervading sense of being trapped in ceaseless misery that A House in Pieces evokes.

It is telling that the strategy to establish an ISIS stronghold in Southeast Asia is centered on Muslim Mindanao’s introverted enclaves. The domestication of extremist ideology in Marawi’s interior, based on the idea of disciplinary and sacrificial purity and the exclusion of the outsider, circumscribes a negative island, a political void harnessed as a strategic focal point for deterritorialized power. Political and economic disenfranchisement and cultural marginalization at home front impel some Muslims to turn to violent fundamentalism. Not to mention that some of them who live in poverty get paid to join the fight.

Lest we think that the national government is a mere observer in this conflict brought about by local and transnational forces, A House in Pieces is the counterfoil that shows how this picture cannot be accurate. The film takes its place alongside documentaries produced in the last five years about the barbarity of the drug war, the violence wrought upon the Lumads, the suppression of the free press, and the undeniable human rights violations perpetrated during the presidency of Duterte. As the state fumbles the rebuilding of Marawi, as it marginalizes Maranaos in the process of the city’s rehabilitation and treats it as a business opportunity, as it further alienates the people and makes them feel forgotten, and as the public ceases to talk about the struggles of the Maranaos, we can gain a sense of how negative islands are formed and how radicalization is nurtured by neglect.

In this context, we can appreciate how A House in Pieces allows us to listen closely to the people on the ground. For Usman, the holy war is unstoppable. For Abdul, the conflict is the failure of the kind and brave Maranaos to transcend their interiority in the name of peace. And for Farhanna, if extremists strike again, there will no longer be any reason to flee and leave home again but every reason to strike back. As far as Usman, Abdul, and Farhanna are concerned — as the documentary captures their mindset — if Marawi’s state of negative islandness —its insularity and the howling abandonment it has had to suffer before and after the war — are not reversed and reoriented toward the flow of many islands, then —as A House in Pieces testifies — we must tremble for the future.

[MindaViews it he opinion section of MindaNews. Patrick F. Campos presented this at the Online Screening and Discussion of ‘A House in Pieces’ on May 23, 2021, the fourth anniversary of Day 1 of the Marawi Siege. Campos is a film scholar, programmer, and associate professor at the University of the Philippines Film Institute where he recently served as Director. He is the author of The End of National Cinema: Filipino Film at the Turn of the Century (2016), co-author of Scenes Reclaimed (2020), and editor of Pelikula: A Journal of Philippine Cinema. Along with regional cinema specialists, he co-organizes the roving biennial Association of Southeast Asian Cinemas Conference, and in Manila, he programs the annual Tingin ASEAN Film Festival. He is a member of NETPAC]