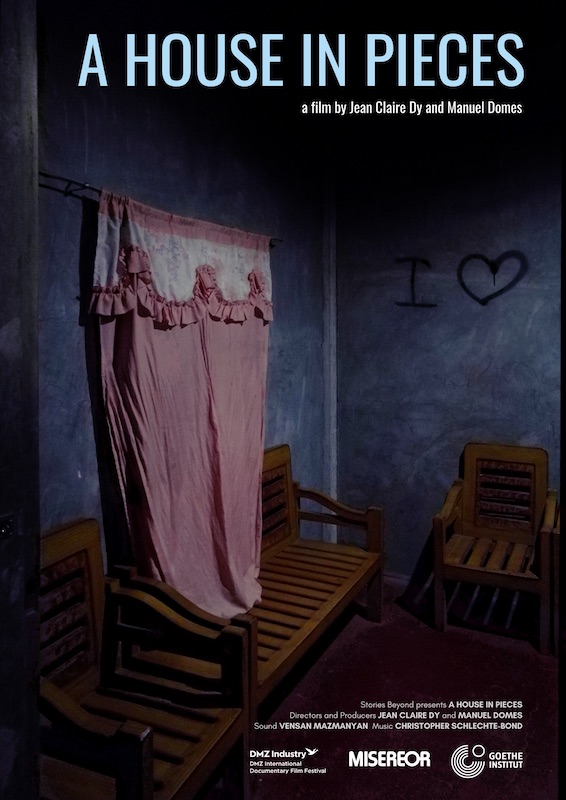

Film: A House in Pieces

Produced by Stories Beyond

Directors and Producers Jean Claire Dy and Manuel Domes

Sound: Venzan Mazmanyan

Music: Christopher Schlechte-Bond

Funded by DMZ International Documentary Film Festival, Misereor Ih Hilfswerk, Goethe Institut Philippinen, and Um Verteilen Stiftung Für Eine Solidarische Weit

Winner: Golden Hercules Award, Kasseler Dokfest, Germany, November 2020

QUEZON CITY (MindaNews / 27 December) — What is documentary filmmaking in the age of Rodrigo Duterte? A House in Pieces — the first full-length feature by the Filipino-German tandem, Jean Claire Dy and Manuel Domes — offers a powerful examination of what it means to make a documentary film in the context of a generalized social terror. When political assassinations are no longer metaphorical but, rather, are grisly realities that make the news every day, we must think more earnestly about the consequences of documenting violence. Namely, we must consider what we gain when a film tries to chronicle conflicts and turns its spectators into witnesses.

A House in Pieces begins in the middle of the story when Yusop, a young carpenter and father, releases a crowd of pigeons. In the madness of fluttering wings, a handcuff dangles from the mesh of the cage, foreshadowing the tales of violence about to unfold — a river filling up with corpses, dogs feeding on human remains, a man getting shot pointblank for not knowing a Muslim prayer. The pigeons fly free as day breaks, circling an old city by the lake where the main dome of a mosque bears the marks of strafing. Before long, a panoramic shot reveals the ruins of Marawi.

Before Yusop and the doves, however, there is the chatter of birds and the voice of a chanter emerging from the morning fog; behind the fog, the outline of a minaret. But before all that, beyond the frame, is the actual beginning of the story when the city was still whole, right before a group of ISIS-affiliated jihadists captured Marawi in May of 2017 to establish a wilayat or Islamic theocracy.

The response from the national government had been swift, leading to brutal clashes with militants that became the country’s longest urban warfare in decades. Duterte eventually placed Mindanao under Martial Law. According to official sources, more than a thousand militants, soldiers, and civilians were killed in the battle that lasted for five months, though the actual figures could be higher. The city’s population was displaced, its residents becoming exiles in their own homeland.

Today, as the author Criselda Yabes notes, much of Marawi remains in shambles, many of its residents still unable to return. Duterte himself has reneged on his word to rebuild the city, its neglect fast receding from the nation’s memory.

Like a ghost that cannot be wished away, A House in Pieces appears at this juncture, compelling us to confront an enormous political predicament. To tell the city’s forgotten present, the documentary film weaves in and out of Marawi in the course of the siege as the camera follows the stories of the refugees. It recounts the journey of Yusop and his family from a makeshift evacuation center back to their home on the outskirts of the city. It tracks the emotional flights of Nancy who sees the destruction of her home, the devastation of her wealth, and the breakup of her family as her children leave Mindanao in search of better days elsewhere. Finally, it relates the thoughts of a young, anonymous businessman who recounts the choice of his friends to sacrifice their lives as jihadists.

Each of these characters feels comfortable with the filmmakers whose voices, especially that of Dy who hails from Mindanao and knows the lingua franca, can sometimes be heard in the background. Together, they give a face to the siege of Marawi, providing the human element to collective destinies that otherwise are largely invisible. Filmed for two years as interwoven tales, A House in Pieces is characterized by great tenderness and honesty. Yet brutality is written all over it.

War, in fact, is key to the history of the medium. The term documentary, for instance, arose in the 1920s and one of its earliest examples was a series of compilation films that recreated the battles during World War I. When World War II erupted, its production was vastly expanded, revealing the longstanding relationship between war and documentary film. The genre, too, had drawn on earlier documentary styles that were rooted in war wherein journalism melded with visual technology to enhance reportage.

Consider photojournalism, a prototype of the documentary style, which began in the nineteenth century when the first pictures of war started appearing in newspapers during the Crimean War in 1853 and the American Civil War in 1861. This trend continued into the twentieth century with Robert Capa’s coverage of the Spanish Civil War, which epitomized a distinct brand of documentary photography. Concurrently, social documentary photography emerged wherein artist turned to the camera to call attention to social ills. Where documentary photography tended to be objective, social documentary photography, in contrast, was more subjective.

In the work of Dy and Domes, however, we see how the journalistic need to document the Marawi siege is combined with impressionist and often poetic images of life in an Islamic city. We regard news clips and interviews, as well as panning shots of the lake and its environs, of burning gardens and embers floating in the air. Here lies the strength of A House in Pieces wherein documentary filmmaking becomes at once detached and haunting. In the film, such commingling can be gleaned from the directors’ attempts not only to document the social and economic ravages of armed conflicts, but also capture the emotional force of life at war.

Such confluence of documentary film and war, as well as the commingling of the objective and the subjective, compels us to think about the work of violence in our day. Namely, A House in Pieces invites us to consider documentary film as the work of witness, everyday life, and generalized violence in the time of Duterte.

Such confluence of documentary film and war, as well as the commingling of the objective and the subjective, compels us to think about the work of violence in our day. Namely, A House in Pieces invites us to consider documentary film as the work of witness, everyday life, and generalized violence in the time of Duterte.

Three scenes capture what I hold to be the key ideas of Dy and Domes’ film. Toward the middle of the storytelling, we find the first scene where Yusop and his family are back in their house following months of staying in the evacuation center. Farhanna, Yusop’s wife, looks toward the ruined city in the distance and tells her child how pitiful it is, how the market she used to frequent is now gone. Around her, children play with bamboo sticks to impale the banana trees. Then the second scene presents Yusop in the backyard, clearing the vegetation with a machete to prevent wild snakes from straying into his house. He stands at rest to recall the time his family tried to flee when the militants came, his heart aching as he gave one last look at the occupied city. Beside him, a mound of uprooted grasses is burning, filling the place with smoke as the passing wind spreads the ashes. Then the film cuts to the third scene: a riverbed where sunlight bounces off the surface of the water. A close up of a hand rinsing a cloth. A passing shot of a minaret.

Running through these scenes are the themes of witnessing, everyday life, and generalized violence, each image building on the other to create a montage that approximates life in the age of Duterte. To wit, the first scene permits the viewers to assume Farhanna’s perspective as a witness. When she looks toward the ruined city, she does so as a witness, and what she sees becomes our vision as viewers. In the film, the gesture repeats itself when Yusop looks back at Marawi as he is about to flee, when Nancy regards the city from her own ruined house, when the businessman steps out of his car to gaze at a once familiar place. All of them turn toward the ruins, as if Marawi were Mecca itself. When they do, they witness centuries of apathy and solitude that once again become their fate as the national government, headed by no less than a Mindanaoan, turns its back on their ravaged city. What they witness is violence perpetrated from all sides, by jihadists and soldiers alike. Violence becomes a city they regard wistfully.

As the film suggests powerfully, violence saturates everyday life in the city. No one can escape it, even after the war. When Yusop recalls how he fled from the city, it is no accident that his remembering happens as he holds a machete. Yusop’s gesture evokes Marawi’s rape; the machete is to Yusop what a gun is to a jihadist. A line runs through all forms of violence. Consider the children’s game as Farhanna recalls the sacking of Marawi. The kids may be playing but to them each bamboo stick is a bullet. This portrayal riffs on the scene in the film’s beginning where the camera chances on Yusop’s son playing a video game involving high-powered weapons. To regard A House in Pieces is to confront how everyday reality, indeed the very notion of normalcy itself, is suffused with violence.

Marawi after the siege does not mean the end of violence, then. To the contrary, the ruins of the city and the afterlives that result from it denote how the everyday has accommodated violence. The third scene is salient in this regard in that it shows a picture far from war, a bucolic landscape seemingly untouched by brute force: a riverbed where a cloth is being washed. But no sooner do we forget about war than we get alerted to it with a brief shot of the pockmarked minaret visible from the riverbank. Such scene evokes Yusop’s remarks about fighter planes patrolling the skies long after the government recovery of Marawi, a reminder of perpetual strife at the heart of ordinary life. The city goes on and learns to live with hostility.

Marawi consequently signifies the generalization of violence. The city is all of us who come to witness violence; it destroys us, and we carry the damage everywhere. More than a place, then, Marawi expresses how violence invades everyday life and shapes everything in its image. With extrajudicial killings met everywhere with a shrug, the whole nation is now grappling with a similar process—a reign of monstrous terror made benign. No one is more responsible for this sad state of affairs than Duterte himself whose face never appears in the film but whose speech resounds as a voiceover. The destruction of Marawi and every act of lawlessness made in his name represent an undeclared yet successful coup on our democracy. This is Duterte’s Eighteenth Brumaire. This, also, is the chilling feat of the documentary. They show what we have all become under his presidency: refugees of normalized cruelty.

(MindaViews is the opinion section of MindaNews. Charlie Samuya Veric, PhD, is Associate Professor of English at the Ateneo de Manila. He is the author, most recently, of ‘Children of the Postcolony: Filipino Intellectuals and Decolonization’)