BOOK REVIEW. Panagkutay: Bringing us right into the Lumad lifeworld

Levy L. Lanaria, Ph.D. A.Th.

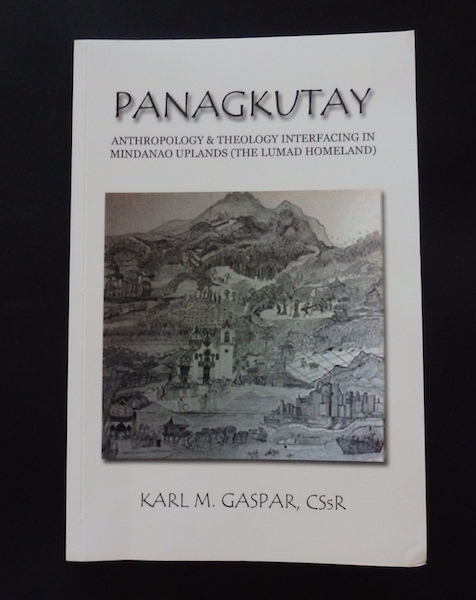

TITLE: Panagkutay: Anthropology & Theology Interfacing in Mindanao Uplands (The Lumad Homeland)

Author: Karl M. Gaspar, CSsR

Publisher: Institute of Spirituality in Asia, 2017

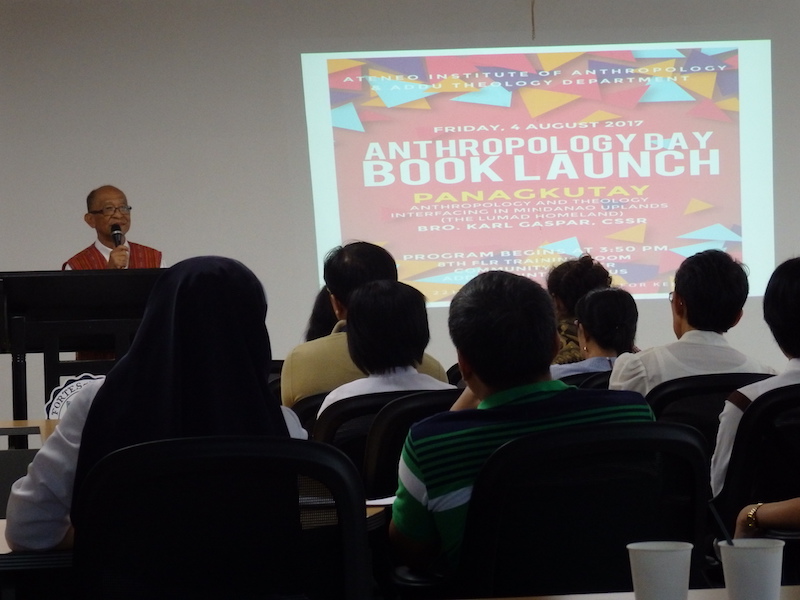

(This review by Levy L .Lanaria, Ph.D A.Th., faculty member at the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies of the University of San Carlos in Cebu City, was read for him by an MA Anthropology student during the book launch of “Panagkutay” at the Ateneo de Davao University on August 4, 2017)

(This review by Levy L .Lanaria, Ph.D A.Th., faculty member at the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies of the University of San Carlos in Cebu City, was read for him by an MA Anthropology student during the book launch of “Panagkutay” at the Ateneo de Davao University on August 4, 2017)

When Brother Karl invited me to do a review on his most recent book Panagkutay I promptly gave my nod. Indeed, it would be a great honor on my part to do it for an icon in the area of Christian social activism and pastoral-educational ministry. Thank you, Brother for giving me the opportunity to share my thoughts and sentiments on another remarkable literary work. This is a work that is grounded on the “joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties” of our indigenous brothers and sisters. Thank you too for bringing the Lumads closer to my consciousness in a way that challenges me to go into some sort of soul searching as an academic.

Bro. Karl’s engaging and challenging book is about his personal-professional experiences and empathetic reflections as an anthropologist-theologian-religious brother with one of the most vulnerable sectors in the country. Hence it is most fitting and proper that he dedicates the book to all the Lumads whom, in his own words, he has encountered across Mindanao in the last 50 years of his life. That’s a great 70% deal of his life outdistancing the number of years he has been a Redemptorist brother! When you read Panagkutay you get connected as well with the author’s autobiography of his public ministry.

I must confess that the Lumads have been almost entirely invisible to my academic radar. My knowledge of development aggression historically rooted in the colonial era that has victimized many a community was very limited – until I read Bro. Karl’s informative/educational literary work. In many history books written by local historians and used as school textbooks they are, in fact, virtually anonymous. This book gives face, flesh and life to their deplorable condition of depravity, sufferings, and pains but also of their struggles and small successes in reclaiming what historically belongs to them. The interdisciplinary work is worth three units in one semester.

The book takes off not from a polished academic runway but from the rough grounds of a very personal pad, certainly very anthropological still and political, which exposes the deep affective involvement of Bro. Karl with his Lumad partners. This is heavy reading, not in terms of the concepts expounded and idioms used but of being vicariously weighed down by the author’s disappointments and frustrations. Sapagkat siya ay tao lamang. Brother has seen it all: both external and internal factors/forces that had converged to render the struggle for self-determination almost an impossible dream. Make no mistake about it. The lament that he unabashedly expressed in Chapter 1 is his calculated way of disallowing the utopian illusion to sap his human spirit and religious energy. For this he wrote the chapter as “an antidote” to his “tendencies at times to romanticize his engagements with the Lumads.” Writing is therapeutic.

Chapter 2 brings us right into the Lumad lifeworld highlighting the urgent issues confronting the indigenous peoples which previous administrations failed to address seriously and consistently. Brother hopes that the current administration (Aquino at the time of the writing) “will do much more.” Today it is Duterte’s. The government must be there but he adds that “in the end, it will be the Lumads themselves who will determine their future.” This early the book serves notices that patronizing and paternalizing approach and attitudes are a no-no to the long-term project of empowerment. The chapter brings closer the major concerns of the Lumads to the readers.

The entire book particularly this chapter brings to light the kind of anthropologist-activist Brother is. His advocacy of self-determination with theoretical underpinning in the post-modern concept of identity politics is a form of self-disclosure. His approach is not to come from a position of superiority but as a dialogue partner with a people who have the right to chart their own future and map out the means on how to get there without losing their shared cultural identity. This is demanded by the ethnographic approach that he has intentionally adopted as an anthropologist-researcher. He refers to it as “experiential participation.” This is, in his words, “pushing to a higher level the method of participant observation.” In more concrete terms, Bro. Karl would enter Lumad territories not so much as a researcher “but as someone present among them to share their griefs and pains, hopes and joys, and whenever the opportunity arises, to be of service in whatever way (he) can but always from their perspective.” Indeed, he was careful that he would not force his thoughts and ideas on the Lumad but “to dialogue with them towards agreeing with them on what was needed to be done.” This dialogical approach is easier said than done for in ethnographic studies should not the deeply involved researcher in pursuit of truth and knowledge maintain some affective distance from the subjects of his/her study lest his analysis and judgement falls prey to unwarranted subjectivism? Apparently, Bro. Karl succeeded in striking the balance not without much reflexive thinking while maintaining his non-neutral political stance.

Chapter 3 puts in a diachronic element to the Lumads’ struggle for self-determination to complement the synchronic in his work. It provides the historical backdrop to their tragic loss of ownership and control over their ancestral territories from Spanish to American to Japanese to American colonization. This portion of the book is a must reading for those of us who possess only a surface knowledge of our indigenous brothers’ and sisters’ situation of depravity. The pockets of rebellion and resistance (ideologically directed or not) can only be adequately understood by those of us outsiders if we take seriously their colonial and neo-colonial provenance. Threatening to bomb a Lumad school is rubbing salt to injury and betrays an unhealthy ahistorical mindset and gross insensitivity to a people long oppressed, long marginalized, long excluded.

What follows all in Chapter 4 is a case study of the Lumad communities in the municipality of Jose Abad Santos of the province of Davao Occidental. The ethnographic study is another eye-opener and heart-breaker. It is a report of the saga of the Lumads’ uphill struggle to claim their ancestral lands inspired by the assistance of concerned partner-groups and reinforced by the historic enactment of the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA) in 1997. Sadly, the political landscape did not change much to improve the people’s lot. As one author puts it and this is worth re-quoting: their lives have “remained stubbornly, frustratingly unchanged.” Bro. Karl shares with us the key reason to the utter lack of progress as pinpointed by Gatmaytan (I find this very interesting): the misconception of equating a land tenure title with autonomy. Autonomy is the core issue traceable to the “historical reality of unequal treatment and relations between the State and the indigenous peoples.”

Chapter 5 is an attempt to bridge anthropology and theology, thus the work’s title panagkutay (“to connect”). This is the part of the book including the subsequent chapter that most interests me as a theologian. Many of us here probably know that for so many centuries the classical theology of the past had privileged philosophy as its dialogue partner, never mind if the relationship is asymmetrical: philosophy as ancilla theologiae (handmaiden of theology). But that is beside the point. Vatican Council gave official impetus to many contextual theologians to enter into a respectful conversation with human and social sciences. The Aggiornamento (“a bringing up to date”) Vatican II Council insists on a Church that is humble, listening and dialogical – a Church that does not pretend to know all the answers to the complex questions of modern men and women. In view of this, “Christians are joined with the rest of men and women in the search for truth, and for the genuine solution to the numerous problems which arise in the life of individuals and from social relationships” (GS 16). Ours is a complex world of myriad problems that the quest for truth and for solution points to the need for theology to enter into a dialogue not only with philosophy but with other sciences. The recognition of the value of the sciences is taken for granted in the liberation theologians’ popular use of the “see-judge-act” pastoral cycle/spiral approach. Bro. Karl employs precisely the pastoral framework in his conceptual and practical engagement as a theologian-activist while tapping the insights of both anthropology-sociology and philosophy.

The chapter focuses the lens on how the local church got involved in the highly contested political space of the uplands. The book traces the church’s shifts in approach in its pastoral ministry with the Lumads. From the traditional proselytization practice, it moved to conscientization and organizing for the Lumads to resist State aggression, then slowly and gradually shifted to inculturation. The seed of inculturation had been officially sown in Vatican II. The discourse on inculturation in the 1970s received a boost from the Federation of the Asian Bishops’ Conferences with its advocacy of an indigenous and inculturated Church. In Mindanao, it would take a while before the seed would sprout. Bro. Karl attributes the very slow reception of the cultural approach to the privileging of the liberational project by the church and its pastoral workers. It was only towards the end of the millennium, according to him, that the church showed greater concern towards inculturation.

A notable development presented by the book was the ecumenical collaboration between Catholics and Protestants to respond to the needs of the Lumad and Moro communities and the realization that Christians must be more sensitive to the IP’s perspective of life and struggle and not impose outside ideas. This view could have been pursued but this had to wait as there was an attempt to contextualize the liberation theology which resulted in the formulation of the theology of struggle.

In time, the sharp militant edge of the IPA network’s liberation theology dissipated. The Vatican II statements on culture and faith were given theological articulations by contextual theologians. The Marxist tradition which informed the liberational project was criticized for its anthropocentric bias anchored on “foreign symbols and values in the name of a universality that was quite destructive of indigenous cultures” (Mcdonaugh).

The discourse on inculturation now began to make, as it were, to gather momentum. The Episcopal Commission on Indigenous Peoples in 1992 and 2010 affirmed the principle and approach of inculturation privileging the rubric of self-determination under the general matrix of total human liberation or integral evangelization. For its part, the Association of Major Religious Superiors in the Philippines expressed “inculturation at the core” in terms of listening, learning their languages, denouncing transgressors, recognizing the sacred. In fact, there has been an abundance of literature about inculturation. Unfortunately, church rhetoric in the observation of Bro. Karl did not translate into a vigorous push by church workers for inculturation, including an inculturated liturgy. There was just little institutional support. The author laments further that the great majority of writers are merely “talking” rather than “walking” about inculturation.

Here Bro. Karl appeals for a collaborative effort among church people who have training in philosophy, anthropology, theology, religious and cultural studies to reflect on the lessons that need to be articulated in the field of inculturation and then to formulate approaches that are practical for workers in this field. The kind of inculturation that Bro advocates does not shunt the emancipatory project of liberation theology. While a lover of theology of liberation, his keen reading of the signs of the times aided significantly by his continual readings as an academician opened his critical mind to the limits and shortcomings of liberation theology. On the other hand, he could not accept an exclusivist notion of identity politics divorced from the basic concerns and needs of peoples. His synthetic stance has been shaped by the probing insights and critical ideas of thinkers-writers from the West (Lynch, Mejido, Zizek), from Africa (Oduyeye, Ukpong), and from Asia (Pieris). Quoting the western thinker-writer Mejido, there is a need to “fuse the symbolic-cultural and the material-economic.” He further anchors his conviction on Pieris’ thoughts on the Asian reality as an interplay of Religiousness and Poverty. For the Asian theologian inculturation and liberation are two names of the same process.

Panagkutay pinpoints popular religion or folk religiosity as a possible stage of an inculturated theological work. To quote him: “One looks forward to a Filipino theologian who would engage the text of Reynaldo Ileto’s Pasyon and Revolution: Populist Movements in the Philippines 1840-1910 and formulate a theological reading which highlights how the Pasyon narrative appropriated by poor peasants was inculturated in the context of a revolutionary agenda.” The book does not mention that there is at least one Filipino theologian by the name of Jose de Mesa, who has, in fact, tapped the liberationist insights of Ileto’s Pasyon in his attempt to construct an inculturated theological discourse using the rich native concept of Loob. He is just one of the few theologians in the country whose passion to pursue the project of inculturation mostly in the sphere of language (footnote: inculturation is not a monochromatic concept) is known by those who were under his mentorship. Unfortunately, frail health has caught up with the Filipino theologian-advocate of inculturation. How many centers of theological studies really offer extensive and intensive training program on inculturation? Individual initiatives are hard to come by, let alone sustain, unless supported by institutional superstructure. But first some kind of paradigm shift must happen in pastoral and theological thinking. Quo vadis ecclesia?

Chapter 6 is a fresh re-iteration and further elaboration of the author’s attempt to engage anthropology and theology in mutual interaction with each other. Martial law was a blessing in disguise because both disciplines came ‘face-to-face’ with each other as academic partners-in-dialogue to make sense of the centuries-old oppression, marginalization, and now exclusion of the indigenous peoples in Mindanao and forge an alliance with an intentionally prescriptive orientation. Marcos’ hegemonic rule made concerned theologians and church workers, including Brother Karl, engaged in indigenous peoples ministry discard the traditional value-free, objectivist and positivist position. Anthropology-cum-theology shifted from merely being descriptive to insistently being prescriptive (reminiscent of Marx’s challenge to philosophy to “change the world”). The shift occurred not without tension in the anthropologist-theologian Karl. He took pains to underscore the normative task inherent of theology, one that envisions a “praxis that more fully embodies the Christian faith and more meaningfully expresses that faith” in terms of the people’s perspectives and capacities.” While at it, he issues a warning: an uncritical appropriation of the social sciences runs the risk of denying “the very principles on which they (theologians) operate and turn them, as Berger suggests, into agents of propaganda” (Gaspar). Anthropology and theology are certainly autonomous disciplines distinguishable from each other, but theology is not subsumable by anthropology.

Post-modern anthropology’s option for identity politics underscoring the cultural constitution of the Lumad communities impacted theology. It turned to culture as a legitimate locus and source of theological reflection and discourse not to blunt but precisely to sharpen the emancipatory design of liberation theology. Here again Bro. Karl is not indulging in arbitrary thinking; in his evolving synthetic anthropological-theological and liberationist-inculturated discourse he has found theoretical frameworks in the writings of theologians like Lonergan, Tracy, Gittins, Arbuckle (who himself is an anthropologist), Gustavo and other Latin American theologians, Pieris, Phan, Berker, Douglas, Geertz, Witvleit, Asad). I remember him telling us his fellow theologians during our annual conference in 2013 in Butuan that he began with social action or practical engagement with the people and later on felt the need for theoretical frameworks to serve as privileged hermeneutical lens in his social-cultural engagement with the indigenous peoples. The social activist has become more scientific; in the see-judge-act method social action needs the insights coming from the academe.

Certainly, one can never accuse Bro. Karl of being an armchair theologian or academic. Many theologians live their academic life safely ensconced in ivory tower so that their theology is not necessarily their spirituality. I must remind myself. The editor’s characterization of Brother’s work as a spirituality book (Fr. Ponce calls it the “spirituality of connecting,” in rhythm with panagkutay) conjures an image of a social activist whose theology is his spirituality. Another point worth noting is that the author’s journey is marked by a number of conceptual shifts in his thinking and approach in dealing with the Lumads: from exclusively political to inclusively cultural, from traditional missiological model of translation (from a position of superiority) to a missiological model that is inculturated (from the perspective of partnership of equals). Indeed, it is worth repeating that Bro. Karl’s book reveals a theologian who has been most attentive to the signs of the times. Under the current administration that is showing no signs of promise in taking up very seriously the Lumad’s uphill struggle for self-determination, I am sure Brother will pursue his project of inculturation with dogged determination and unshakeable faith in the God of history that he has been despite numerous setbacks.

Let me bring to a close my review parallel to how Bro. Karl ended his book. As the anthropologist opened his book with a lament, he ends it by a ringing appeal in his Epilogue addressed to all of us: “it is my hope that this book reminds us that the situation is desperate and that time is no longer on our side.” Take it from a post-modern prophet who listens, writes, talks, and walks.