(This piece written by H. Marcos C. Mordeno was first published in the book, “Transfiguring Mindanao: A Mindanao Reader,” edited by Jose Jowel Canuday and Joselito Sescon, published by the Ateneo de Manila University Press and launched on June 22, 2022 in Davao City. See Part V on “Mediating Truths, Contested Communities, Making Peace.” Permission to share this with MindaNews readers was granted by the Ateneo University Press)

First part

Self-help

In general, the people behind the production of the newsletters had little, if any, training in journalism, writing and photography. Apart from dedication, it was enough that they knew the basic elements of a news story – the five W’s and one H (What, Who, When, Where, Why and How). They obtained this knowledge through documentation workshops handled by individuals whose main credential was having undergone the same activity ahead of them, and relatively longer experience in such tasks. Others sought to hone their skills by studying whatever references they could lay their hands on.

And, with scant resources, they started with mere fact sheets printed using the now outdated mimeographing machine and low-quality paper. Most of them could not even afford a print output with photos that they had to make do with mere drawings and caricatures in an attempt to make the publications more appealing. The bright side was that the rather low-cost, backward mimeograph technology allowed cash-starved organizations to produce more than enough copies for their target readers.

This was not the case, however, for a number of human rights groups and research institutions. Compared to most mass-based organizations, they had enough support from foreign donors (government, non-government and Church-run agencies) with which to hire skilled writers, most of whom came from the ranks of activists and former campus writers. From time to time, the writers had the opportunity to undergo seminars and trainings handled by professional journalists and photographers. (Some of these writers became reporters for national and regional newspapers in the post-Marcos era.)

The steady inflow of external support also meant they could afford to churn out publications of high-quality materials using printing presses. Some even had at least two regular publications (usually a regular newsletter and a magazine that came out less frequently), not to mention occasional print materials focusing on specific issues. This was particularly true of human rights groups with national and regional networks such as the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines (TFDP) and the Ecumenical Movement for Justice and Peace (EMJP).

The TFDP-National Office published the fortnightly Philippine Human Rights Update magazine, and its regional office in Mindanao based in Davao City put out the monthly Mindanao Human Rights Monitor. EMJP’s national office published its own Justice and Peace Issues magazine while its Mindanao office based in Cagayan de Oro City produced the monthly Mindanao Advocate. There were also provincial TFDP and EMJP offices which put out their own newsletters. On rare instances, like in Iligan City, the local TFDP and EMJP offices published a common newsletter. And it was not uncommon for TFDP staffers in Mindanao, including this writer, to contribute articles to the Mindanao Advocate.

Young people today, that is, those who have become inured to the fast flow of information through the internet, may find it odd to hear about fortnightly or monthly publications. But it was understandable in a setting where getting stories from the rural areas, where most military abuses occurred, required time, caution, creativity and, most important, courage, without which one’s technical skills and intellectual asset would have meant nothing.

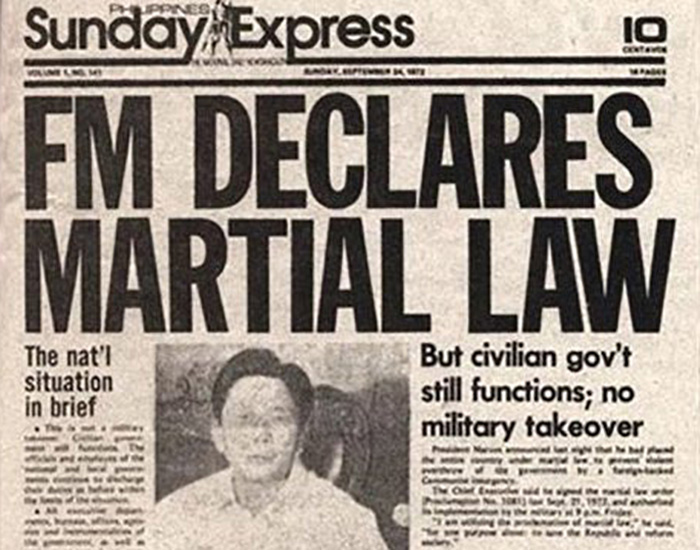

This leads to the question of how stories that exposed the brazenness of the Martial Law regime saw print and were read not only in the country but also abroad.

Local Documentation Networks

Professional journalists get their stories by approaching sources and doing research to support and/or validate facts. Furthermore, current technology such as email and the mobile phone allows them to interview their sources from a distance and gives them a safe way to transmit their stories to the editors.

The Martial Law era organizations that ran newsletters and other publications also approached sources (victims and witnesses), did their own research, and observed a process of verification. Like professional journalists, they knew the importance of getting accurate, unassailable facts to maintain reliability and credibility. The only difference was the absence of advanced technology that could have made the delivery of information faster. In those days, the handheld transceiver radio, a luxury then, was the only means of mobile communication one could have access to.

As such, data-gathering needed to be done in places where the stories happened. It meant going to conflict-affected zones and militarized areas, enduring rigorous rides and treks across rugged terrain, and running the risk of dealing with abusive soldiers and government militiamen. In an atmosphere marked by mutual suspicion and distrust, the presence of outsiders would endanger not only the human rights workers themselves but also their hosts. For example, evacuees returning to their homes in a village in Claveria, Misamis Oriental onboard a cargo truck had to hide this writer in a discreet part of the vehicle before stopping at a checkpoint. The group leader explained that the soldiers could tell who were residents and who were not, and this writer’s presence would have invited suspicion and possibly reprisal.

Not even a press card could guarantee one’s safety in conflict zones. Soldiers in the field were wary of everybody, that even professional journalists from reputable media entities had to be discreet in going in and out of these areas. Being able to enter a conflict zone without going through the slightest difficulty was a privilege that not many enjoyed.

This writer did experience some brushes with the military on his data-gathering trips to militarized areas. In one fact-finding mission in Karomatan (now Sultan Naga Dimaporo) town in Lanao del Norte that I joined, a fragmentation grenade was thrown at the mission members while we were sleeping in the church premises. Luckily, the grenade failed to explode as the attacker only removed the preliminary pin, not the safety pin. The most frightening incident was being chased by mortar fire in a village in Misamis Oriental after one of my colleagues switched on his flashlight while negotiating a trail along a denuded forest in the middle of the night. The soldiers stationed a few kilometers away must have seen the illumination and presumed that we were rebels.

But adversity breeds ingenuity. Since it was impractical to visit those areas on a regular basis, security being the paramount consideration, TFDP provincial offices organized local documentation networks in remote villages. These were comprised mainly of residents who came from grassroots and church lay organizations with ample literacy in the vernacular and trained in basic documentation. They performed the data-gathering work if it was not possible for victims and witnesses to go to the cities or towns where TFDP offices are based. Without them, TFDP’s publications would not have stories to publish, and the world would not have known the extent of human rights violations in the country. These grassroots networks served as the umbilical cord between the victims and TFDP.

The local documenters showed their resourcefulness in smuggling written accounts past military checkpoints where soldiers would often inspect bags and cargoes and bodily inspect passengers. For example, in Claveria, Misamis Oriental where such inspections intensified during the imposition of “resource control,” a euphemism for a food blockade, in 1984–1985, they would write the accounts on the inner side of a “bulsita” (brown paper bag) that they stuffed with camote (sweet potato) and other crops. Others, women in particular, would tuck the papers in their bras. They resorted to these and other ingenious methods after one of them nearly got caught carrying a written account, and only evaded possible harm by eating the paper before the soldiers could frisk her.

TFDP also owed much to priests and missionary nuns and lay persons stationed in rural areas. They too provided initial information or write-ups on incidents of military abuses or personally accompanied victims and witnesses to be interviewed. Generally trusted by the people in the community and viewed as their protectors, it was easy for them to convince the victims and witnesses to speak up and tell their stories.

Read the last part

(“Transfiguring Mindanao: A Mindanao Reader” has 34 chapters with 44 authors mostly coming from Mindanao covering broad topics from history, social, economic, political, and cultural features of the island and its people.

The book is divided into six parts: Part I is History, Historical Detours, Historic Memories, Part II is Divergent Religions, Shared Faiths, Consequential Ministries, Part III is Colonized Landscapes, Agricultural Transitions, Economic Disjunctions, Part IV is Disjointed Development, Uneven Progress, Disfigured Ecology, Part V is Mediating Truths, Contested Communities, Making Peace and Part VI is Exclusionary Symbols, Celebrated Values, Multilingual Future. Edited by Jose Jowel Canuday and Joselito Sescon, this book is a landmark in studies on Mindanao.

Get your copy: Website: bit.ly/TM-aup, Shopee: bit.ly/TM-s, Lazada: bit.ly/TM-lzd.

Watch the book launch here: bit.ly/TM-booklaunch)