(This piece written by H. Marcos C. Mordeno was first published in the book, “Transfiguring Mindanao: A Mindanao Reader,” edited by Jose Jowel Canuday and Joselito Sescon, published by the Ateneo de Manila University Press and launched on June 22, 2022 in Davao City. See Part V on “Mediating Truths, Contested Communities, Making Peace.” Permission to share this with MindaNews readers was granted by the Ateneo University Press)

Background

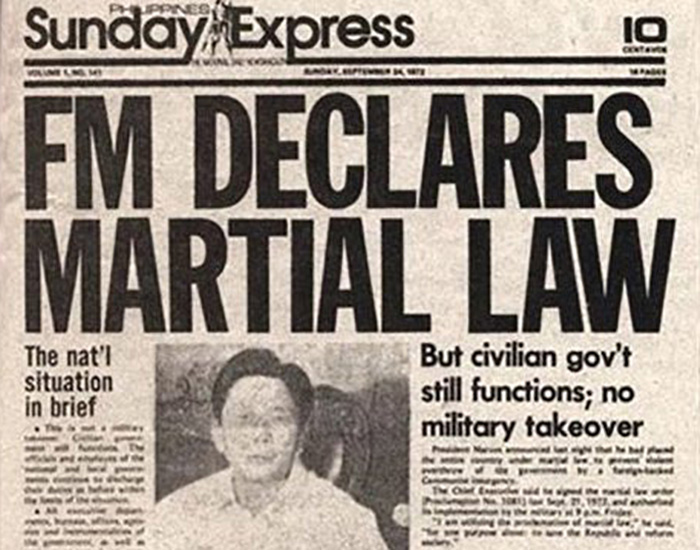

The Philippine press used to take pride in itself as the freest, if raucous, in Asia. That was prior to the declaration of Martial Law by President Ferdinand E. Marcos in September 1972, an event that led to either the forced shutdown or State control of media establishments and the silencing of critical writers, commentators and journalists. From being a vibrant and uncompromising institution, the country’s Fourth Estate became nothing more than a cog in the apparatus of authoritarian rule.

Censorship took its toll not only on the metropolitan press but also on media outlets in the provinces, including in Mindanao. For example, dxDB-Malaybalay, a Catholic Church-run radio station in Bukidnon that started in July 1971, and its sister print outlet, Bandilyo sa Bukidnon, were padlocked sometime in 1977 on orders of then National Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile. The station and newsletter had continued to air and publish stories on human rights abuses in the province after Martial Law was declared, which apparently angered the military whose response, the closure order, clearly sent across the message that it would not countenance any criticism of its actions and policies.

Indeed, reporting on wrongdoings by government officials could prove risky — nay, fatal, as in the case of Demy Dingcong, an Iligan City-based reporter for a national daily. Dingcong had written about graft allegations against a politician in Lanao who was close to Malacañang. Days after, he was shot dead inside his house. The murder was never solved, but even the Moro National Liberation Front, in an issue of its underground newsletter, blamed it on the politician who was the subject of Dingcong’s story.

Both instances, the closure of dxDB and Bandilyo sa Bukidnon, and the murder of Dingcong, demonstrated the repressive and constricted atmosphere within which the media worked during martial law.

The “Alternative Press”

Aside from clamping down on press freedom and freedom of expression, the imposition of Martial Law forced the political opposition to lie low for a number of years. However, mounting abuses committed by the military, in particular, contributed to a burgeoning people’s movement, both legal and underground. Far from muffling the voice of protest, such abuses only led to the unintended outcome of fanning the flame of social unrest. In the countryside, military abuses proved to be the best recruiter for the New People’s Army.

The assassination of the popular opposition leader Senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. on 21 August 1983 led to further political polarization and engendered wider resistance to Marcos’ rule, calling for either his resignation or his ouster. On the media front, various groups urged readers to boycott newspapers that served as mouthpieces of the dictatorship. At the same time, some journalists found the courage to establish newspapers and magazines that came to be collectively called the “alternative press”. These included Ang Pahayagang Malaya, Mr. and Ms. Magazine, the short-lived Philippine Signs, and, shortly before the ouster of Marcos, the Philippine Daily Inquirer, which evolved from the Inquirer Magazine, a publication solely dedicated to the developments surrounding the Aquino-Galman double murder case then being tried by the Sandiganbayan.

How to define “alternative press” may be open to discussion, but suffice it to say that it referred to publications that carried news which the pro-Marcos media, pejoratively called the “crony press,” would rather not air or print. Marcos called the “alternative press” the “mosquito press,” perhaps because they pestered him no end until his ouster in February 1986.

This development undermined the dictatorship’s control of the flow of information, although the situation hardly resembled the media landscape prior to Martial Law. In fact, We Forum, a sister publication of Ang Pahayagang Malaya founded by press freedom advocate Jose Burgos, was raided sometime in 1985. In Zamboanga del Norte, human rights lawyers Jacobo Amatong and Zorro Aguilar were murdered on 23 September 1984 while preparing for a fact-finding mission on the killing of a human rights researcher in the province. Aguilar was editor of the local paper Nandau (Today’s News in Subanen language). If Marcos allowed some space for the “alternative press” to thrive, it was because he wanted to show that his government was anything but

authoritarian.

Rise of Micro-Media

Ordinary Filipinos had limited access to newspapers and magazines at the time. Moreover, only the middle- and high-income families could afford a television set. Radio, therefore, served as the main source of news and information for the majority. However, the radio stations that continued operating during Martial Law knew they faced closure if they did not toe the line. A few individual commentators, like then debonair opposition leader and former Assemblyman Reuben Canoy of Cagayan de Oro City, managed to voice some criticisms against Marcos, albeit subdued, compared to those coming from militant groups. But others of lesser stature opted to play it safe.

Churches, sectoral organizations, human rights groups and other institutions filled the information void created by the atmosphere of fear during martial law through micro-media. Their reach may not have been as pervasive, but they signified an awakening, the gradual yet steady erosion of fear and rebirth of courage among an otherwise cowed citizenry.

The definition of micro-media has evolved over time and with the growing influence of the internet. But in those years and in the context that gave rise to it, micro-media loosely referred to newsletters and bulletins with limited numbers of copies and imbued with a social mission. This explains why many of the newsletters carried such names as “Lingkawas” (Break Free or Liberate) and the more restrained “Banika” (Countryside) and “Bidlisiw” (Sun’s Ray). They started as humble one-page statements and manifestos, usually distributed in a discreet

manner to evade problems with authorities.

Sectoral organizations produced newsletters written mostly in the vernacular and distributed mainly among their members. The articles dealt with matters closest to their hearts, for example, agrarian issues for farmers, and news on the labor front for workers. Human rights groups, on the other hand, focused on military abuses, and used English in an attempt to attract readers from the more literate sectors such as professionals, church people, lawyers and students.

For the newsletters of organizations broadly categorized as Left-leaning, the common element, content-wise, was the emphasis on the repressive character of the Marcos regime. The stories could therefore be faulted as being one-sided and biased, relative to the ethics and standards of good journalism, and may be dismissed as propaganda. Yet, in a situation where the mainstream media only reported “the good, the true and the beautiful,” as former First Lady Imelda Marcos would put it, such “one-sidedness” and “bias” served as a useful, if effective, counter-narrative. It accomplished the purpose of offering the readers an alternative presentation of social realities that the dictatorship sought to mask through a controlled media.

In addition to human rights groups, the Martial Law regime gave rise to institutions in Mindanao that concerned themselves with issues other than the violations of civil-political liberties but are related to it. They focused on the socioeconomic landscape – documenting and publishing about labor practices, trends in the regional economy, the impact of transnational corporations on

agriculture and other industries, to name a few. Their work aided in providing a wider context to the human rights situation, e.g., by establishing a link between the phenomenon of militarization in an area and the presence or impending entry of major industries and plantations that threatened to displace entire communities.

Their major outputs included the publications on the construction of Pulangi IV, a hydropower facility that diverted water from the Pulangi River in southern Bukidnon to form an artificial lake, erasing some villages from the map and displacing their residents; and the farm practices of a fruit giant, i.e., the seasonal nature of its employees and the harmful chemicals being used in its plantations. The company reportedly became so concerned, if not alarmed, by the adverse findings that it offered to buy all the copies of the booklet that was published about it.

One of those institutions is the Davao City-based Alternative Forum for Research in Mindanao or AFRIM, a research agency that continues to exist to this day. It publishes the Mindanao Focus Journal, Bantaaw and books featuring the results of its research and policy analyses. Another is the Cagayan de Oro City-based Datalink Mindanao or DALIM, the entity that published the booklet on the farm practices of the fruit giant mentioned earlier. DALIM stopped operating sometime in 1990 after its officers and staff members moved on to other jobs.

Meanwhile, in Bukidnon, the forced shutdown of dxDB and Bandilyo did not stop some priests from denouncing human rights violations and other abuses. Fr. Godofredo Alingal, a Jesuit priest assigned in Kibawe town, started a Blackboard News Service, popularly known as “Kibawe Budyong,” after the closure of the diocese’s two media outlets. He installed a huge blackboard in

front of his church, on which he posted news about official abuses that were otherwise suppressed. He put up a new one each time the blackboard was vandalized.

Alingal began getting death threats from anonymous sources. One of the threats said, “Stop using the pulpit for politics…your days are numbered.” But he just shrugged it off, saying, “The priesthood is not a safe vocation.” He was murdered on 13 April 1981.

Second part

(“Transfiguring Mindanao: A Mindanao Reader” has 34 chapters with 44 authors mostly coming from Mindanao covering broad topics from history, social, economic, political, and cultural features of the island and its people.

The book is divided into six parts: Part I is History, Historical Detours, Historic Memories, Part II is Divergent Religions, Shared Faiths, Consequential Ministries, Part III is Colonized Landscapes, Agricultural Transitions, Economic Disjunctions, Part IV is Disjointed Development, Uneven Progress, Disfigured Ecology, Part V is Mediating Truths, Contested Communities, Making Peace and Part VI is Exclusionary Symbols, Celebrated Values, Multilingual Future. Edited by Jose Jowel Canuday and Joselito Sescon, this book is a landmark in studies on Mindanao.

Get your copy: Website: bit.ly/TM-aup, Shopee: bit.ly/TM-s, Lazada: bit.ly/TM-lzd.

Watch the book launch here: bit.ly/TM-booklaunch)