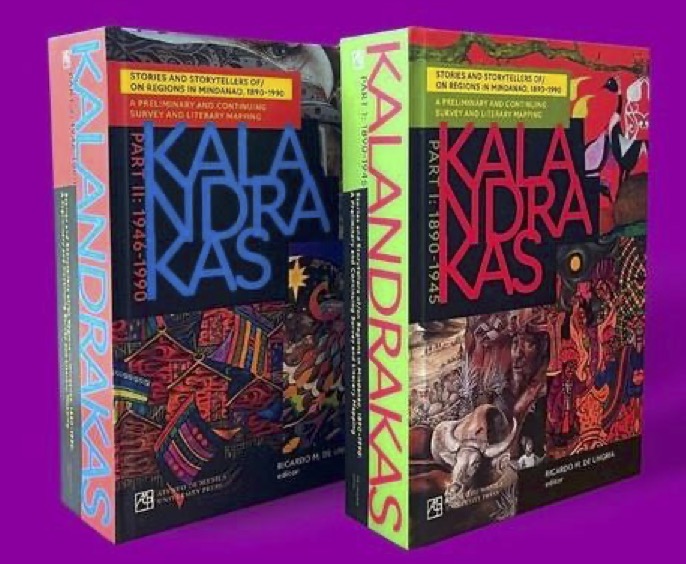

Kalandrakas: Stories and Storytellers of/on Regions in Mindanao, 1890-1990, A Preliminary and Continuing Survey and Literary Mapping by Ricardo M. de Ungria. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2022.

In one of the appendices (Appendix E) of Ricardo M. de Ungria’s newest anthology titled Kalandrakas: Stories and Storytellers of/on Regions in Mindanao, 1890-1990, A Preliminary and Continuing Survey and Literary Mapping, the editor mentions a basic premise in doing archival projects important in developing literatures in the regions: “to reject (or refuse or eventually reject) the hegemonic and homogenous kind of thinking of the state and sectors in the capital region, and to give focus, precedence, and credence to the capability of regions to define and support the arts and cultures particular to each of them” (p. 1156). This is, perhaps, the disposition that guides the anthology.

Kalandrakas, the book, promises to be the most comprehensive anthology that compiles works in/on Mindanao from 1890-1990. It is Ricardo de Ungria’s fourth venture into anthologizing texts that map out the literary terrain and topography in the southern part of the Philippines. It follows Habagatanon: Conversations with Six Davao Writers (2015), Voices on the Waters: Conversation with Five Mindanao Writers (2018), and Songs Sprung from Native Soils: More Conversations with Eight Mindanao Writers (2019), which all feature writers and their veritable milieus in the shattered islands of Mindanao and Sulu. These anthologies undergird the cultural texts that are ever-present but have become absent in the consciousness of Philippine literature.

The introduction to the book implicitly calls the project “archival” or “archaeological” as it digs, culls, and collects materials that could be representatives of the lifeworlds and struggles in the island region and its nearby archipelago. We are reminded here of Isabelo de los Reyes’s monumental project El Folklore Filipino (1889), which aspired to make an archive of “indispensable materials for the understanding and scientific reconstruction of Filipino history and culture” at a time when the pangs of Spanish colonialism marred the nation. Like El Folklore Filipino, De Ungria’s anthology is also mixed and hybrid in its content – not just indigenist but also keen on the borrowed pieces about Mindanao made by foreigners. De Ungria defines the Sugboanon Binisaya word “kalandrakas,” after all, as “a coming together of a variety of things, a mixed bag, sundry matters, a miscellany, close to chaotic but not quite” (3). It is the same as how American linguist John U. Wolff in A Dictionary of Cebuano Visayan (1972) denotes “kalandrakas” as a “conglomeration of various things or kinds” and “things of all different kinds and varieties coming at once” (p. 1317).

What constitutes the earnestness and relevance of the anthology is its two huge volumes that present 249 writers and their companion pieces. The volumes are periodized according to important events in Philippine colonial narratology. The first part spans the period from 1890 to 1945, which takes off from three Cagayan de Oro writers (identified as Vicentico Neri, Justiniano Abellanosa, and Toribio Chavez) and Jose Rizal’s exile in Dapitan up to the end of the Pacific War. The second part covers 1946 to 1990, which lays bare the pieces during the year the country gained independence from the United States of America and the year the Third Republic was inaugurated up to the closure of US military installations in Central Luzon in 1990s. Aside from the pieces (the editor calls them “stories,” which includes all genres of literature), the two volumes each contain a thought-provoking introduction written by the editor, uneven biographical notes, and a congeries of appendices that include further readings and short narratives from magazines, a directory of Mindanao writers, and a proposed framework for archival projects and developing literatures in the regions.

One may deduce that De Ungria, the editor, elides persistence and dedication for unearthing and consolidating all the pieces in the anthology. I am myself appreciative of De Ungria’s uncommon diligence in contributing to the development and trajectory of Mindanao and Sulu literature. However, I would like to raise three inquiries to speculate on the other ways and pathways to decolonizing our understanding of Mindanao and Sulu literature. As the editor suggests in his introduction: “decolonization process [that] should help lead us forward to the selves we still carry within us but extricated from and rid of colonial baggage” (9). That said, I am opening a space for conversation.

First, there is a lack of engagement in including foreign writers in the anthology. While the editor mentions that “there are things to be learned” from the colonizers, the “discussion and decision [should] better be left to the regions themselves” (5). In this particular statement, where does the editor stand? Which regions does he expect to engage in the discussion he paves the way to? How do we negotiate, for example, with the works of American anthropologist Fay Cooper Cole who called the Indigenous Peoples of Davao “wild” like “animals”? In the anthology, the editor did not engage with Fay Cooper Cole’s assumptions on the usage of “wilds” and “tribes,” which both connote “fossilization” and a specific stage of evolution. These words resemble White guilt, which is now being questioned by many scholars and researchers from “Critical Indigenous Studies.”

Take, for example, Fay Cooper Cole’s observation from “The Wild Tribes of Davao” included in the anthology: “There is no organization of the tribe as a whole, since each district has its local ruler who is subject to no other authority. These divisions are seldom on good terms, and are frequently in open warfare with one another or with neighboring tribes” (133). This passage on the Mandaya having no social organization is clearly an outsider’s point of view that needs to be challenged. The social organization followed by the Mandaya probably differs from what Fay Cooper Cole knew, which is, frustratingly, barely engaged in the anthology. The editor could have interrogated these speculations to reconcile Fay Cooper Cole’s inclusion in the book with decolonizing Mindanao and Sulu literature.

Second, the reader would be led to infer that a joyful celebration and an enthusiastic appreciation are the key actions for strategically developing robust Mindanao and Sulu literature. The editor suggests: “For now, I see no pressure to ‘theorize’ on regional literatures, much less on Mindanao literature. What is of the moment is to start thinking differently about giving due appreciations for the literatures we have and to keep our writers writing in the regional languages they know and our literatures alive and in ferment” (32). This is where time and reflection might have interceded efficiently. There is a much-needed interrogation and theorizing needed on how Sugboanon Literature in some parts of Mindanao is marginalized in the entirety of Sugboanon Literature that only tends to focus on Cebu and its adjacent province Bohol. Kalandrakas, the book, should assert that much theorizing is required in fighting for the legitimacy of Sugboanon dialects in Mindanao that would question “regional hegemony” in contests, publications, and conferences organized by power-generated institutions.

Furthermore, it can be surmised that we could meaningfully develop “local theories” that could organically spring from the gargantuan amount of folk materials in Mindanao and Sulu. These theories are significant in decolonizing the materials in regional literatures that adhere to dominant ideologies, such as the grand narratives found in some archives, histories, institutions, and even anthologies like Kalandarakas. What might have been a discourse-oriented book is thus reduced to a celebratory-oriented one.

Finally, the crux of the matter is the periodization used in dividing the two volumes. The anthology refuses to face and “historify” the real problems in Mindanao and Sulu by subscribing to the Filipino nationalist agenda. Instead of using the important events in the center as a scaffold – the 1896 revolution up to the Pacific War, and the inauguration of the Third Republic up to 1990s – the editor could have framed the periodization after the significant incidents and circumstances that contributed to the centuries-old narrative of conflict and struggle in the island region and its nearby archipelago. The Treaty of Paris in 1898, where Mindanao and Sulu were included in the cession of Spanish colonies to the United States of America, and the Jabidah Massacre in 1968, which resulted in the establishment of the Moro National Liberation Front and Moro Islamic Liberation Front, could be used as a point of departure for each volume. These two events contoured the shape of everyday lives in Mindanao and Sulu – evident in the wars and conflicts people endure – compared to the current periodization used by the editor.

In its current form, the anthology erases these narratives of dispossession and systemic violence brought about by the ineffective state policies that limit the demands and needs of the various communities in the southern Philippines. The editor could have referred to his proposed framework found in Appendix E of the book: “reject the hegemonic and homogenous kind of thinking of the state and sectors in the capital region” (p. 1156). It is imperative, indeed, for the anthology to liberate itself from the frameworks and lenses imposed by the nationalist hegemonic orders and practices.

Perhaps, these inquiries may be needed and relevant to our imagination of an idealized past, a tormented present, and a future yearning in Mindanao and Sulu.

(Jay Jomar F. Quintos taught Literature at the University of the Philippines-Mindanao in Davao City from 2014 to 2020, moved to UP in Diliman during the pandemic but served as affiliate faculty of UP Mindanao, teaching online from 2020 to 2022. He is presently on study leave, taking his PhD in Indigenous Studies at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand. His research interests are focused on Mindanao and Sulu Studies)