DAVAO CITY (MindaNews / 16 August) – A multi-hazard simulation drill will be conducted by the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) on Saturday morning, August 17, in Kusiong, Datu Odin Sinsuat in Maguindanao, one of the hardest hit villages during the magnitude 8.2 earthquake that triggered a tsunami and left at least 8,000 dead and missing on the same date 43 years ago.

Maguindanao recorded the highest number of deaths, followed by Zamboanga del Sur and Lanao del Sur when the country’s “most disastrous tsunami” struck just after midnight on August 17, 1976, affecting 700 kilometers of coastline bordering the Moro Gulf, hitting Maguindanao, Sultan Kudarat, Lanao del Sur, Lanao del Norte, Zamboanga del Sur, Basilan, Sulu and the cities of Cotabato, Zamboanga and Pagadian.

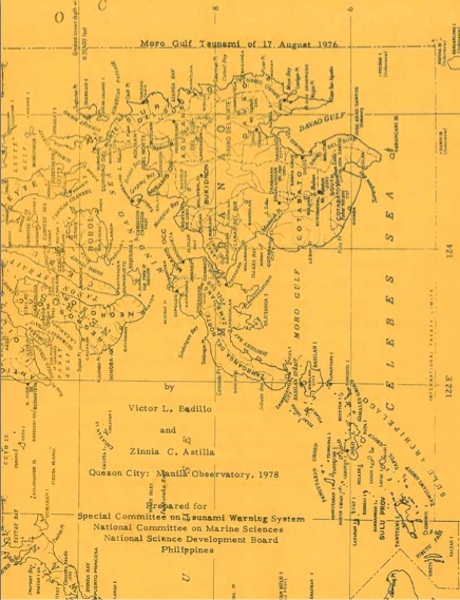

Cover page of the 1978 report on the Moro Gulf Tsunami of 17 August 1976.

Cover page of the 1978 report on the Moro Gulf Tsunami of 17 August 1976.

About 95% of the deaths were due to the tsunami, according to the 1978 report written by Fr. Victor L. Badillo and Zinnia C. Astilla of the Manila Observatory for the Special Committee on Tsunami Warning System, the National Committee on Marine Sciences and National Science Development Board,

“About 8,000 were dead or missing. About 10,000 were injured and about 90,000 were homeless,” the report, intended primarily to “present findings about this tsunami for a better understanding of it and that steps may be taken to lessen loss to lives and property in future tsunamis,” said.

Saturday’s simulation scenario involves a magnitude 8.1 earthquake at 7 a.m. with epicenter along the Cotabato Trench in the Moro Gulf, generating a tsunami. There is no time to issue a Tsunami Warning. Among the severely affected coastal communities in the BARMM is Kusiong, where scores die, are missing or injured by tsunami waves as high as 10 meters (33 feet). Several fisherfolk also need to be rescued as their boats capsized. But the road to Kusiong is blocked by uprooted trees, large stones and other debris caused by tsunami and landslide. Power and communication lines are totally cut off.

Kusiong was chosen as the venue for the simulation drill because “it was one of the hardest hit areas during the 1976 Tsunami as it lies directly in front of the Cotabato trench,” said Local Governments Minister Naguib Sinarimbo, who heads the regional disaster response mechanism of the six-month old regional autonomous government: the Bangsamoro READi (Rapid Emergency Action on Disaster Resilience).

But is Bangsamoro READi ready to respond to a scenario like that in the simulation drill?

Sinarimbo acknowledged that they are “not yet at a level of readiness in the BARMM that we can be comfortable with” in terms of responding to possible tsunamis and other disasters but “we are working on it.”

He told MindaNews on Friday that they are “undertaking preparedness at every level of the local government units, from barangay to the region.” The August 17 simulation drill in Kusiong is part of the preparations.

“We are educating coastal communities and we are expanding our network by bringing in the BIAF (Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces) and the other institutions of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)” to help in the disaster response, he said.

Sinarimbo is confident that with the Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM) councils that should be in place in all levels of the LGUs, and with Bangsamoro READI as the regional operations center, “we can now integrate the response of the regions and the LGUs vertically. We are also doing a horizontal integration of our response with the other ministries. We can bring in the national through the Office of Civil Defense.”

Under Section 15 of Republic Act 10121 or the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010, the local DRRMCs take the lead in preparing for, responding to, and recovering from the effects of any disaster: the barangay DRRMC if a barangay is affected; the city / municipal DRRMC if two ore more barangays are affected; the provincial DRRMC if two or more cities / municipalities are affected; the regional DRRMC if two or more provinces are affected and the national DRRMC if two ore more regions are affected.

Saturday’s simulation drill aims to “test the preparedness / readiness and know-how of the residents during calamities; determine the level of preparedness of the communities and learn from them what training / education or capacity enhancement needs that the Council or its four Pillars & members should undertake or formulate; test the effectiveness of Command Control System, particularly Incident Command System (ICS), Communication, Coordination, and Support System etc.; test the RDRRMC’s existing institutional system/organization; test/evaluate and improve existing Contingency Plan (CONPLAN) relative to each type of disaster, fine-tuning various elements of disaster response operations in a multi-disaster and complex emergency scenarios; and Showcase vital disaster response capabilities within the Golden Hour (First 72 hours) such as Search and Rescue (SAR), Mass Casualty Incident Management, Evacuation, among others; and Provide a venue by which the Council could offer a wider scale of disaster awareness among all stakeholders, particularly the communities and the general public.”

1976 death toll

In 1976, Maguindanao’s death toll was 2,608 from the tsunami (1,815 dead and 793 missing) and 131 from the quake (103 dead and 28 missing). Zamboanga del Sur recorded 1,134 (582 dead and 552 missing); Lanao del Sur posted 1,156 (755 dead and 180 missing from the tsunami and 41 from the quake); and Sultan Kudarat posted 391 (229 dead and 52 missing from tsunami; 79 dead and 32 missing from the quake).

In this photo taken in March 2011, Babu Minang Katug Blao of Linek in Datu Odin Sinsuat, Maguindanao, a survivor of the 1976 tsunami, visits the grave of her mother and other relatives who died on August 17, 1976. The marker indicates they died “August 17, 1976 tsunami.” MindaNews file photo by TOTO LOZANO

In this photo taken in March 2011, Babu Minang Katug Blao of Linek in Datu Odin Sinsuat, Maguindanao, a survivor of the 1976 tsunami, visits the grave of her mother and other relatives who died on August 17, 1976. The marker indicates they died “August 17, 1976 tsunami.” MindaNews file photo by TOTO LOZANO

Among the cities, Pagadian City recorded 746 (447 dead and 229 missing) while Zamboanga’s record was 198 (111 dead, 87 missing). In Cotabato City, the record was 281. But more people died from the quake (110 dead, 93 missing) than the tsunami (57 dead, 21 missing).

The 1978 report also noted that there had been “more severe tsunamis, but areas hit were less populated and had less man-made structures.”

“A natural disaster is not merely a geophysical event but a human one as well. If any projection can be made it is this: What is now barren will be densely populated. Empty beaches will be filled with residences, tourist facilities, hotels, factories, power plants, etc.. Offshore, there will not be merely seaweed an oyster farms and fish corrals but also storage facilities, tank farms and the like. Thus, a tsunami prone coast is potentially a great disaster area,” the 1978 report warned.

Local inundation maps

The 1978 report recommended that an “immediate and realizable goal” would be “to require local officials to prepare local inundation maps” which are basically “a street map of a town with dangerous areas to be evacuated crosshatched.”

“These maps can be drawn empirically by knowing which areas were inundated by past tsunamis. If there are contour maps available, one can determine all areas below a chosen height above sea level, for example six meters, as places to be evacuated,” the report said.

The maps, it added, could also be useful to “engineers, architects, land use planners, building code drafters, insurance agencies and the like.”

The report stressed that it is “impossible” for a national agency to provide warning to inhabitants about to be hit by a tsunami generated by a local earthquake.

“It would be fatal to wait for a radio broadcast and the like before moving into action. There is already a warning available, one provided by nature herself – the violent shock of an earthquake. If the shock is violent enough so that it is difficult to stand or walk then it is time to seek higher ground at once. Going to a higher ground will not mean going a long distance if local inundation maps exist and are known,” the report said.

But the report also noted that “it is one thing to have these maps and quite an altogether different thing for people to use them. What becomes clear is that education is needed, an extremely difficult task, a never finished task.”

Hazard maps useless without drills

In March 2011, after the tsunami in Japan, MindaNews was able to reach one of the authors of the 1978 report — Badillo, a Jesuit priest, astronomer, former director of the Manila Observatory (an asteroid was named in his honor in 2005 for having popularized astronomy in the Philippines).

Badillo said the local inundation maps that the report recommended should be done “are really easy to make. The storm surge hazard maps are a good start. What is needed is to use a street map and superimpose on it a map that shows the heights above sea level, both of which already exist. Then on the assumption of a three meter height wave, one can see where one can run to.”

In Honolulu, another tsunami prone area, “there is a drill once a month,” he said, adding that hazard maps “are useless if there are no drills.”

“We cannot wait for national action. I believe the local government units should take the initiative. Making the maps will not cost anything. It is having the drills that may cost money,” he said.

Moro Gulf’s tsunami history

Badillo warned that “the submarine earthquakes that cause tsunami in the Moro Gulf and nearby have an average interval of about 17 years. So the area is already pregnant.”

Before the 1976 tsunami, the report done in 1978 listed four other submarine earthquakes of great magnitude that occurred “beneath the Moro Gulf area or the immediately neighboring Celebes Sea” — August 15, 1918 (8.3); March 14, 1913 (8.3); August 21, 1902 (7.25); September 21, 1897 (8.7); and September 20, 1897 (8.6). Tsunamis caused by submarine quakes of smaller magnitude happened on December 19, 1928 at magnitude of 7.25; March 2, 1923 (7.25); January 31, 1917 (7); ); August 21, 1902 (7.25); February 5, 1889; and December 21, 1636 or a frequency of “one every nine years.”

“What becomes apparent is that the Moro Gulf area has been the most tsunami prone area of the Philippines,” the report said.

The report quoted a 1977 statistical study of tsunamis in the Philippines by Nakamura, that found the Moro Gulf area to be “the most tsunami prone, followed by Eastern Mindanao, then Western Luzon.” The report said “further geological and seismological studies should indicate prospects of future activity in this area.” (Carolyn O. Arguillas/MindaNews)

READ:

35 years after the 1976 tsunami: whatever happened to the preparedness plans?

The 1976 tsunami: Maguindanao had highest death toll

Babu Minang, survivor of 1976 tsunami: “Nothing was left”

Moro Gulf Tsunami of 17 August 1976

[pdf-embedder url=”https://mindanews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/MoroGulf_1976complete.pdf”]