Build, Build, Build’ hits chokepoint

DPWH under Duterte: Corruption, politics, slippage mar many projects

By Malou Mangahas and Karol Ilagan

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

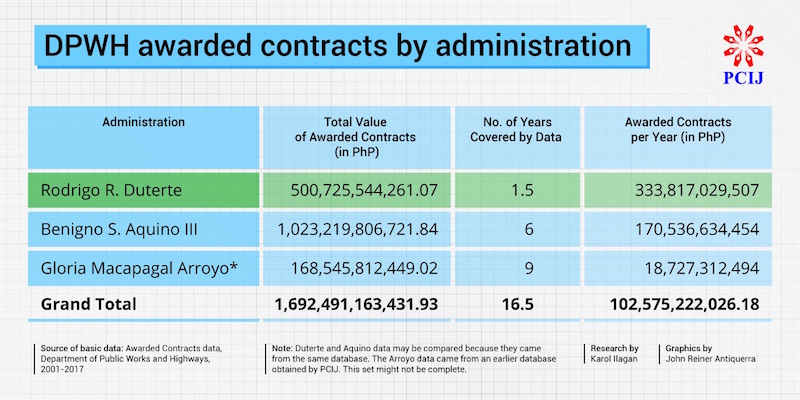

IN THE TWO years since he assumed office and promised to usher in a “golden age of infrastructure”, President Rodrigo R. Duterte has put money where his mouth is. Boasting that, by his term’s end in 2022, multiple roads, bridges, ports, and airports will rise across the nation, his Build, Build, Build program now has a potential bill upwards of PhP8.4 trillion that will come from public funds, private monies, and loans.

By a Cabinet secretary’s account, Duterte is simply unstoppable when he wants to get something done. First christened “Dutertenomics,” the mammoth Build, Build, Build program currently has tens of thousands of civil-works contracts bidded out, apart from multiple multibillion-peso big infrastructure projects partly funded by official development assistance (ODA) or loans from China, Japan, and other bilateral partners.

This dwarfs the infrastructure frenzy under one of Duterte’s predecessors, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who is said to have had an “edifice complex” so bad that roads and bridges were being built at a speed that would make it possible for her to inaugurate one or two in her visits to the provinces week on week.

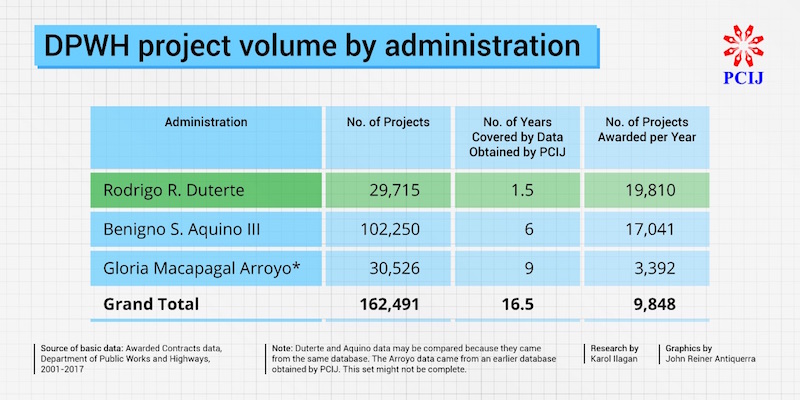

As a result, the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) during the Arroyo administration bidded out 27,535 civil-works contractsin eight years, from 2000 to 2008. But this has turned out to be just 60 percent of the Duterte administration’s total projects bidded out, which come to 44,000 in all, according to DPWH Secretary Mark A. Villar, in a mere 24 months, from July 2016 to July 2018.

If Villar’s number is correct, that total redounds to an average of 1,833 DPWH projects awarded monthly, or 60 projects daily. Apart from roads and bridges, DPWH is also building schools, flood-control systems, and water systems, while other agencies are constructing irrigation, power systems, as well as ports, airports, and other civil-works projects.

Like Arroyo – now the Speaker of the House — Duterte has proclaimed his massive infrastructure program as an anti-poverty antidote. He wants, he has said, to build infrastructure and bolster industries so he can create jobs and curb poverty by nearly half, or from 21.6 percent in 2015 to between 13 and 15 percent in 2022.

In addition, like Arroyo and all presidents before him, Duterte has promised that his projects and administration would be rid of corruption. “I assure you,” he had said at the launch of his socio-economic agenda in 2016, “this will be a clean government.”

Regressive results

But contractors, current and former officials, procurement experts, and affected citizens interviewed by PCIJ have separately offered guarded to cynical prognoses about Build, Build, Build. Indeed, most say that the program could be falling or crashing down due to its own massive weight, and is now yielding not progressive but regressive results after two years of Duterte.

Not surprisingly, they also say that corruption remains a formidable feature in many of the projects that are supposedly aimed to improve the lives of people.

“Year 1 marks the launch, the testing period, for Build, Build, Build,” said an executive of a big contractor. “Year 2 is when it unravels and encounters problems. By Year 3, the chokepoint, it would be difficult to save it.” Next year, 2019, the program and the Duterte administration will turn three.

But DPWH Secretary Villar offers a rosy picture still. “I wouldn’t say that it’s hitting any snags,” he told PCIJ in an interview. “It’s not without any challenges. It’s not without the challenge, but my statement about the Build, Build, Build is we’re on track and it is improving and the support is there.”

DPWH, the government’s engineering and construction arm and an implementor of major projects under Build, Build, Build, receives the biggest infrastructure allotment as well as the second biggest budget annually among the departments. This year, DPWH was allotted PhP637.9 billion, reflecting a 40-percent increase from its PhP454.7 billion budget in 2017.

But while Villar seems unperturbed by “snags” in Build, Build, Build, observers and insiders alike say that these are significant enough to hinder the program’s progress.

For one, they affirm in separate interviews, some local, legislative, and public works officials colluding with favored but unqualified contractors are “syndicated” circles of corruption that continue to stalk many of the projects.

Greed and need

In fact, as early as February 2017, contractors had noted in meetings with public officials that “implementing agencies, especially in remote regions, continue to become victims of local government officials and in some isolated cases even national government officials who influence the award of projects to favored sub-par contractors.”

“There is a need,” the contractors had thus said, “to craft measures to insulate and isolate infrastructure projects from political intervention which has become syndicated.”

A senior official with expertise and insight into the problems meanwhile observed, “Greed is driving project contracting, the projects are falling below accomplishment targets, most projects are bloated.”

Apparently, the bigness of the projected bill of Build, Build, Build — about 5.4 percent in 2017 to 7.4 percent in2022 of gross domestic product, or PhP8.4 trillion in all in five years (compared to the PhP2.4 trillion or so total infrastructure budget during the Aquino administration’s six years) — has also magnified multiple-fold the opportunities as well as the costs of corruption. And with the focus often on the money to be made, many projects have wound up suffering from poor planning and monitoring, and are awarded with unsettled right-of-way or in some areas, security issues, among others.

Project identification, evaluation and approval, as well as the competitive public bidding, notice of award, and local government permits and clearances, have also run into delays until mid-year, or by the onset the rainy season, thus impeding actual construction work, or even the deployment of workers, equipment, and aggregates.

In addition, there is the fact that there are just too many projects to do, prompting some big and small contractors to enter into subcontracting arrangements but submitted as joint venture agreements. Several small contractors, in violation to procurement rules, have even resorted to borrowing the licenses of some big contractors, in exchange for flat two- to five-percent fees out of the total project cost.

Bad and corrupt projects, according to various sources, result when agencies fail to identify the right and needed projects; the procurement process is not competitive or is marred by collusive bidding and influence-pedding by politicians and contractors; project cost is not commensurate to desired project quality; and implementation of projects is not monitored and achieved within deadline.

Back in harness

To be sure, corruption and inefficiency have long marred public-works contracts. In 2009, for instance, PCIJ reported that Arroyo’s rush to roll out projects resulted in obscure contractorsbagging billion-peso worth of contracts even though there wasn’t enough proof that they were capable of doing quality work.

Eight years later, with Duterte at the helm, contractors with a history of blacklisting, registration revocation, graft cases, poor performance, and political ties have again emerged as the top firms moving earth to open roads to traffic.

In 2010, DPWH under then Secretary Rogelio Singson launched reforms to improve the integrity of its procurement process, starting with standard unit cost analysis per project before going to public bidding across the board. Bidding for national projects became more transparent, competitive, and less vulnerable to corruption. Yet contracts awarded by local engineering districts, and those funded by the Priority Development Assistance Fund or “pork barrel” funds at the time were not spared by some politicians who, according to reports, still collected payoffs.

This kind of corruption in road projects has lingered under the Duterte government. In a 2017 dialogue conducted by the Construction Industry Authority of the Philippines (CIAP), “politics and political intervention” still emerged as a key concern among contractors. The situation, according to one former government official, even “discourages good and honest contractors from doing projects in certain regions where contractors are designated as project takers.”

CIAP initiated the dialogue to determine the capacity and readiness of the construction industry to take on projects under the Build, Build, Build program. Representatives of the DPWH, National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA), Department of Transportation (DOTr), Department of Education (DepEd), Government Procurement Policy Board (GPPB), and contractors’ associations attended the dialogue.

Tong-pats, taripa

Two senior government officials and at least four contractors separately interviewed by PCIJ on condition of anonymity said that for the most part, the system has only evolved and adapted to policies of DPWH officials through the years. One contractor said, however, that in many areas where the same politicians have ruled for long periods, backroom deals between and among elected officials, firms, and DPWH engineers have not changed, making them “the biggest mafia” in the country.

Under Arroyo, when profiting from infrastructure projects were more or less an open secret, kickbacks came in the form of “tong-pats” (patong) or an amount added to the actual cost of the project to accommodate the commission rate of local politicians. According to contractors, the rate at the time was about 12 percent of the contract price.

This figure apparently had to go down during the term of President Benigno S. Aquino III, when then DPWH Secretary Singson initiated across-the-board cuts on project costs to minimize public funds being pocketed by officials. But then “tong-pats” merely morphed into “taripa(tariff),” or portions of project costs already earmarked for kickbacks.

One contractor recalled how he had to negotiate with a congressman and a local DPWH official to lower their rates to eight percent and two percent, respectively, and leave the contractor with a profit of at least another eight percent. In all, the three-part sharing scheme meant that 18 percent of project cost had already been set aside for taripa and profit, even before groundbreaking rites for the project.

Another contractor meanwhile confirmed that politicians also get “assistance” from contracting firms for their election or reelection campaigns.

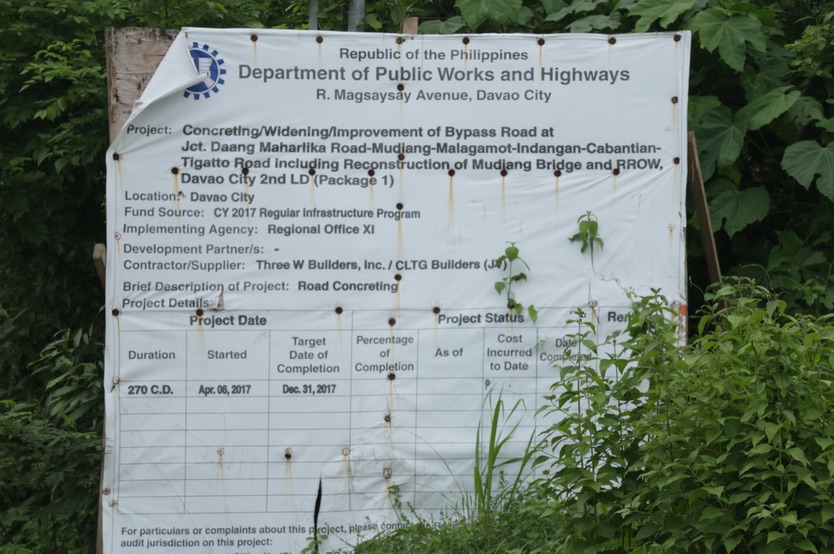

Project covered by a joint-venture agreement between Three W Builders and CLTG Builders. Completion deadline was December 2017 yet. PCIJ Photo by John Reiner Antiquerra

Project covered by a joint-venture agreement between Three W Builders and CLTG Builders. Completion deadline was December 2017 yet. PCIJ Photo by John Reiner Antiquerra

‘Joint-ventures’ on the rise

Behind closed doors and without paper trail, these deals unfold outside the purview of regulatory bodies, and beyond the formal scope of the procurement rules. Of late, legal loopholes have also allowed contractors and taripa-seekers to still corner contracts and commissions, resulting in fly-by-night firms winning some of the biggest projects.

In the last two years, an increasing number of “joint-venture” agreements have been sealed, providing a supposedly legal way-out for smaller contractors to win huge contracts — which they would not have qualified to get on their own — by “using” the license of bigger, much more established contractors.

On paper, both small and big contractors are expected to implement the project. In reality, on ground, only the small contractor gets the project and implements it. According to those privy to such arrangements, a “royalty fee” worth two to five percent of the total contract amount is paid to the big contractor for “lending” its license.

Such set-ups are most obvious in “joint ventures” where the “authorized managing office” is the representative of the small firm and not of the big firm, said one contractor. The source added that because the small contractor is not really capable of completing the JV project, the project gets delayed.

There are also cases when a public official is himself the contractor. Two contractors separately told PCIJ of a governor who supposedly gets all infrastructure projects in his bailiwick by making deals with Triple-A contractors, which, through their licenses and qualifications, bid and win projects for the governor’s firm. But the projects actually go to the governor’s construction firm while the Triple-A contractors each get a “fee” in the deal.

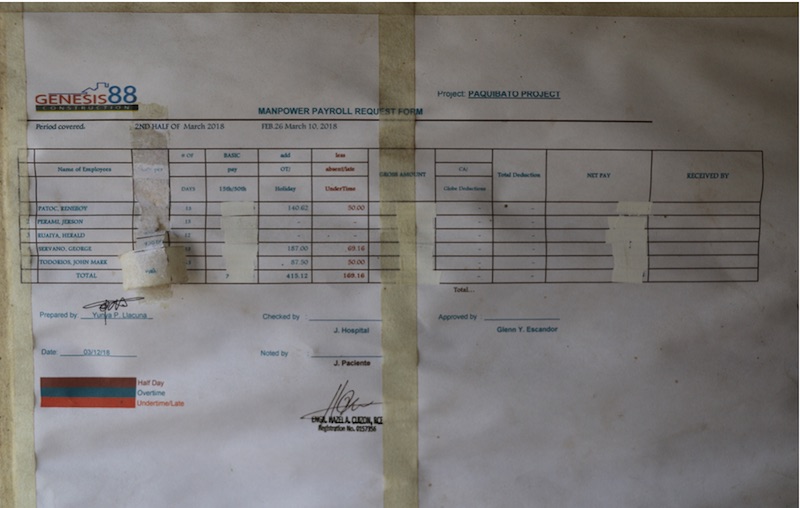

There was no governor involved in a project PCIJ stumbled upon in a field visit to Davao City last June. But it did find a company owned by Davao businessman and presidential assistant for sports Glenn Escandor working on a project that had been won by another firm.

Projects lost, found

Among other things, PCIJ had gone on field to take a look at a project that was supposed to be at 0.22 percent accomplishment rate as of April 30, 2018: the PhP24.8-million rehabilitation/reconstruction of the Mabuhay-Pañalum-Paquibato Road with slips slope and landslide” in Davao City. The project, which on paper was to be implemented by Las Piñas-based Three W Builders Inc., was supposed to have started on May 4, 2017 and completed by Oct. 21, 2017. Three W is a Triple-A contractor.

PCIJ failed to locate the project but instead found another Three W project: the PhP44.8-million “construction of slope protection along Lasang River, Paquibato Proper Section, Davao City.” The actual work for the project, however, was being done by Genesis 88 Construction Inc., an A-licensed construction firm owned by Escandor. The project engineer, the payroll request form, and the backhoe at the project site were all from Genesis 88. No Three W Builders employee was on site.

Backhoe and equpment of Genesis 88 Construction owned by Presidential Assistant for Sports Glenn Escandor at the site of a project supposed to be implemented by Three W Builders. DPWH has no record of Genesis 88 being awarded this project. PCIJ Photo by John Reiner Antiquerra

Backhoe and equpment of Genesis 88 Construction owned by Presidential Assistant for Sports Glenn Escandor at the site of a project supposed to be implemented by Three W Builders. DPWH has no record of Genesis 88 being awarded this project. PCIJ Photo by John Reiner Antiquerra

As of this writing, Genesis 88 and Three W Builders have yet to respond to letters sent by PCIJ despite multiple follow-up calls made to each of their staff personnel.

Procurement rules allow subcontracting under certain circumstances only. A contractor like Three W may subcontract portions of the works, provided that it will undertake, using its own resources, not less than 50 percent of the contract works in terms of cost. At the same time, subcontractor is supposed to subcontract not more than half of the work. Moreover, it should be a PCAB-licensed contractor with Net Financing Contracting Capacity (NFCC), which is computed based on its net worth as submitted to the Bureau of Internal Revenue and the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Prior approval of the head of the procuring entity — in this case the Davao City 1stDistrict Engineering Office — is required as well before subcontracting is allowed. But District Engineer Wilfredo Aguilar and Assistant District Engineer Milagros de los Reyes of Davao City said that no application for subcontracting has been processed by their office. They said, though, that it is possible that Genesis 88 may have rented its equipment to Three W or Three W hired Genesis 88’s employees for the project.

Dismal disbursement rate

For sure, illegal or irregular deals could have only helped lead to the dismal findings regarding DPWH that the Commission on Audit (COA) recorded in its 2017 Annual Audit Report of the agency.

For instance, government auditors found, of the total PhP610.9 billion obligated by DPWH, only PhP222.66 billion or 34 percent was disbursed because of delayed and non-implementation of infrastructure projects. According to the report, DPWH was not able to implement:

- 2,334 projects worth PhP62.59 billion, which were not completed within the contract period;

- 135 suspended projects costing PhP6.07 billion;

- 15 terminated projects amounting to PhP2.1 billion; and

- 815 unimplemented projects worth PhP2.58 billion.

On the same day that news broke about the COA report last July, President Duterte in a speech in Davao City warned that he would hold DPWH Secretary Villar accountable for delayed and failed projects.

Said the President: “I would like to call the attention of the secretaries, especially Secretary Villar, that if there is any slippage of any work of any kind by the national government. If you delay or if I see tomorrow, beginning tomorrow, and you are all invited to see me in Malacañang.”

“Kaya sinasabi ko sa inyo, I’m exacting now something of like this. ‘Yangproject mo pagka pumalpak(If your project fails),I will hold the Secretary responsible,” Duterte added.

Four days later, on July 11, Villar clarified details raised in the COA report and announced that DPWH had started investigation proceedings “for suspension of 43 contractors” behind the 400 projects with slippage or facing implementation delays.

Interviewed by PCIJ last Aug. 19, Villar acknowledged that there is a problem but qualified the findings in DPWH’s context. He said that the obligation amount used by COA includes multi-year projects, which was reportedly why disbursement was pegged at 34 percent. By DPWH calculations, he said, the agency’s disbursement rate stands at 60 percent for “all funds, all legal bases.”

DPWH’s data

Data provided by DPWH show that of its 2017 total PhP672.97-billion amount obligated, PhP406.48 billion had been disbursed. (According to a former DPWH insider, however, the amount the agency records as having disbursed usually “includes carryover projects from previous years, since disbursement by agency is cumulative.”)

Villar also said that the aggregate number of infrastructure projects is 44,000, making the percentage of the delayed projects — 2,334 by COA’s report — only five percent of the total. DPWH spokesperson Anna Mae Lamentillo meanwhile said that the portion of suspended projects over the total number is at three percent, making the statistics actually “good.” But DPWH did not confirm if the aggregate number refers to 2017 projects only, which was COA’s reference.

COA also found that DPWH did not impose liquidated damages on the contractors or rescind or terminate any of the 120 delayed projects that have already incurred negative slippage of 15 percent. These delayed projects are worth PhP6.67 billion.

The 2016 Revised Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act No. 9184 provides that a procuring entity such as DPWH “may rescind the contract, forfeit the contractor’s performance security and takeover the prosecution of the project or award the same to a qualified contractor through negotiated contract” in case that the delay in the completion of the work exceeds 10 percent of the specified contract time plus any time extension granted.

Lamentillo, though, said that rescinding a contract is optional, highlighting the law’s use of the modal verb “may.” She said that DPWH does not automatically terminate a project because sometimes it becomes more expensive for the government to re-award it. Bidding alone, she said, usually takes about three months. If the contractor is able to comply with its catch-up plan, said Lamentillo, DPWH allows the firm to continue and complete the project.

Multiple reasons

COA allowed that the delay, termination, and non-implementation of the DPWH projects were caused by various factors, ranging from the agency’s responsibilities such as right-of-way acquisition, inadequate planning, monitoring, and supervision of projects, and lack of cooperation with local government units to address contractors’ concerns such as having insufficient workforce and equipment. Late issuance of permits, peace and order issues, and unfavorable weather conditions were likewise among the reasons cited for project delays, said COA.

But it noted that consultants and the DPWH management failed to consider these during the preliminary engineering study on the viability of the projects. Moreover, COA said, these same issues have been noted in the prior years’ audit reports.

“Had management considered the right-of-way and project site issues during the preliminary engineering study on the technical viability of the project, the same could have been resolved prior to project implementation or the proposed projects could have been excluded in the final list of projects for bidding,” COA said.

“These problems should have been disclosed during the planning stage and properly discussed during the BAC (Bids and Awards Committee) meetings when deliberations for projects implementation were conducted with Management officials to arrive at decisions advantageous to the government,” it added. “Likewise, coordination with concerned government agencies and private companies should have been conducted early and regularly to address the permit issues and follow-up the release of permits.”

More hires, reforms

An ex-DPWH official said of COA’s comments on the right-of-way issue, though, “If DPWH does not take some risk and will only budget a project once the full right of way is completed, then many infra projects of government will never get started. Landowners delay actual turnover of land if they know that there is still no budget for the project.

In any case, PCIJ asked Villar how DPWH was going to address the problems pointed out by COA since more projects will have to be undertaken with the Build, Build, Build program. He replied in part by saying that DPWH is about to hire almost 4,000 additional project engineers and has organized for job fairs to help contractors find personnel.

“I’m not saying that it’s not difficult,” he also said. “It’s difficult and all of us are working 24/7 to solve these issues.”

The DPWH chief also cited technology as one solution to address issues of corruption and irregularities in civil-works contracts. He said that DPWH is promoting the use of applications and analytics to minimize discretion, and in turn, to minimize corruption.

For example, Villar said, having a satellite based geo-tagging system makes it difficult to cheat on the reporting of project status. He also said that being able to see constantly updated records from a central database has allowed DPWH for the first time to use analytics.

Analytics fan

Villar — the youngest to serve in the DPWH and by some contractors’ accounts the least prepared for the job — described himself as a firm believer of analytics. Any major company that handles huge volumes of work needs analytics, he said.

“That’s what we’re doing,” said Villar. “The more use of analytics, the more use of quantitative measurements. It minimizes discretion, therefore you minimize corruption.”

He disagreed with the view that technology cannot or may not capture cases of collusive bidding, lending of licenses, and illegal subcontracting that all happen behind closed doors. Technology could still capture these irregularities to a certain extent, he argued.

“These construction companies that supposedly ‘subcon’ (subcontract) — if they are held to be more accountable for their projects, if we’re better at monitoring — we can more or less see who the low-performing contractors are,” said Villar. “More or less, these are the ones who have low capability.”

DPWH uses an application called InfraTrack, which is supposed to improve transparency and accountability in the monitoring of civil-works projects. It uses geotagging technology to help the agency monitor the progress of projects virtually.

Politicians’ picks?

According to Villar, DPWH has used the system to identify the 43 contractorscurrently facing suspension over delayed projects. One of the 43, R.C. Tagala Construction, which is now operating under the name Syndtite Construction Corporation, was recently blacklisted for one year beginning Aug. 16, 2018.

Asked to comment on allegations that politicians have been known to “place” their favored regional director or district engineer in their bailiwicks, Villar replied in part by saying that he also uses metrics in assessing the performance of DPWH district engineers.

According to Villar, people make recommendations to his office, but he always refers to his grading system, which is based on performance composed of disbursements, bid variance, and design and quality audits scores. District engineers are then ranked from one to 99. Those ranked at the bottom might be floated.

“I don’t approve these recommendations, I make a choice,” the secretary said. “People can recommend but ultimately, I make a choice. For operational decisions, if he’s (district engineer) underperforming, he goes.”

‘A careful politician’

Since Villar became public works secretary, at least 10 percent of district engineers have been floated. All of the district engineers in the Cordillera Administrative Region, for instance, have been replaced because, said Villar, they were performing poorly.

But contractors interviewed by PCIJ noted that Villar has been acting like a careful politician from a political family with vast business interests in real estate, retail, and water services. Commented one contractor: “He is careful not to offend political allies and friends.”

The secretary is the younger of two sons of real estate mogul and former Senate president Manuel Villar and re-electionist Sen. Cynthia Villar. The Villars lead the Nacionalista Party, with Foreign Affairs Secretary Alan Peter Cayetano among its members. Mark Villar is married to Emmeline Aglipay, until recently the DIWA party-list representative who was named Justice undersecretary last August. Mark Villar himself gave up his seat in Congress shortly after being appointed to head the DPWH in July 2016.

PCIJ asked Villar why his Statement of Assets, Liabilities, and Net Worth shows that he has zero investments in Vista Land & Lifescapes, Inc., a multibillion-peso integrated property developer owned by his family, as well as whether he got the DPWH post as a return favor for the election campaign donation said to have been given by the Villars to Duterte.

Villar replied with a general comment. “I don’t involve myself,” he said. “If there’s anything that I feel would be any conflict, I wouldn’t do it myself. I don’t have any investments in anything.”

Debt of gratitude

The President himself, however, has been open about his fondness for the Villars.

In March 2017, Mark Villar’s father, former Senate President Manuel B. Villar, was part of Duterte’s business delegation to Thailand. Before a crowd of Filipinos, President Duterte heaped praise on Villar as “isa sa pinakamabait, pinakamabait na tao. Hindi marunong magmura ‘yan. NagingSpeaker namin ‘yan. Ni minsan, ‘di ko nakikita – nagingcongressman ako panahonSpeaker siya — wala akong narinig na mag-init ‘yung ulo (one of the nicest people I have met. He doesn’t curse, and not once — when I was a congressman, he was the Speaker — have I seen him blow his top).”

For the elder Villar, Duterte said, “Para sa akin, puwede ako magpakamatay sa kanya kasi mabait eh (I could die for him because he is nice.)”

More than just fondness, however, Duterte has acknowledged that he owes the Villars gratitude.

At a public event in October 2017, he said that Mark Villar’s mother, Sen. Cynthia A. Villar, helped him during the election campaign in 2016. News reports reported him as saying, “During the presidential debates, in between far and wide the debates, there was this intermission. Nakita mo wala akong advertisement. Walang pera eh. Buti na lang tumulong siMa’am Cynthia. Tinulungan niya ako.I have to admit it, na tinulungan ako.(I had no advertisements, no money. It was good that Ma’am Cynthia helped me. She helped me. I have to admit it, she helped me.)”

At a public event in October 2017, he said that Mark Villar’s mother, Sen. Cynthia A. Villar, helped him during the election campaign in 2016. News reports reported him as saying, “During the presidential debates, in between far and wide the debates, there was this intermission. Nakita mo wala akong advertisement. Walang pera eh. Buti na lang tumulong siMa’am Cynthia. Tinulungan niya ako.I have to admit it, na tinulungan ako.(I had no advertisements, no money. It was good that Ma’am Cynthia helped me. She helped me. I have to admit it, she helped me.)”

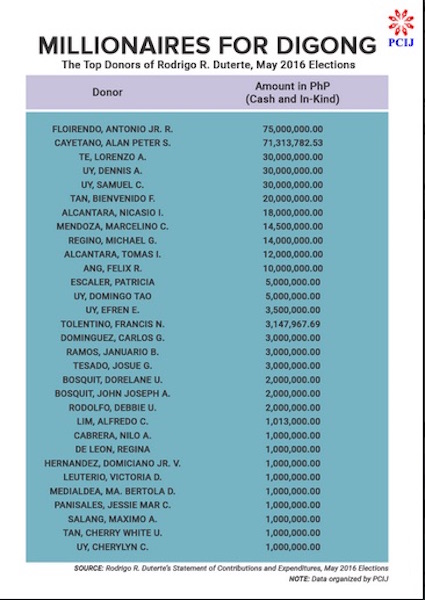

In the campaign spending report that he submitted to the Commission on Elections, Duterte did not name the Villars to be among his donors in the 2016 elections. PCIJ in December 2016 had reported that of the PhP371.36 million in campaign donationsthat Duterte raised, 89.28 percent or PhP334.8 million came from 13 multimillion-peso donors. One of them, Marcelino Mendoza, gave PhP14.5 million. A resident of the Villars’ bailiwick of Las Piñas City, Mendoza is listed as an incorporator, board member, and stockholder of the Villar family’s Vista Land conglomerate. — With additional reporting by Carolyn O. Arguillas and John Reiner Antiquerra, PCIJ, September 201