By Malou Mangahas

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

LAST JULY 2, after being declared ineligible to bid for the multibillion-peso contract to rebuild Marawi City’s conflict zone or “most affected area (MAA),” a consortium led by a China state-owned enterprise filed a motion for reconsideration with the Task Force Bangon Marawi (TFBM).

As of this writing, the Task Force has yet to decide with finality on the consortium’s motion. Yet on the same day that the motion for reconsideration was filed, TFBM began negotiations with another group, also led by a China state-owned enterprise.

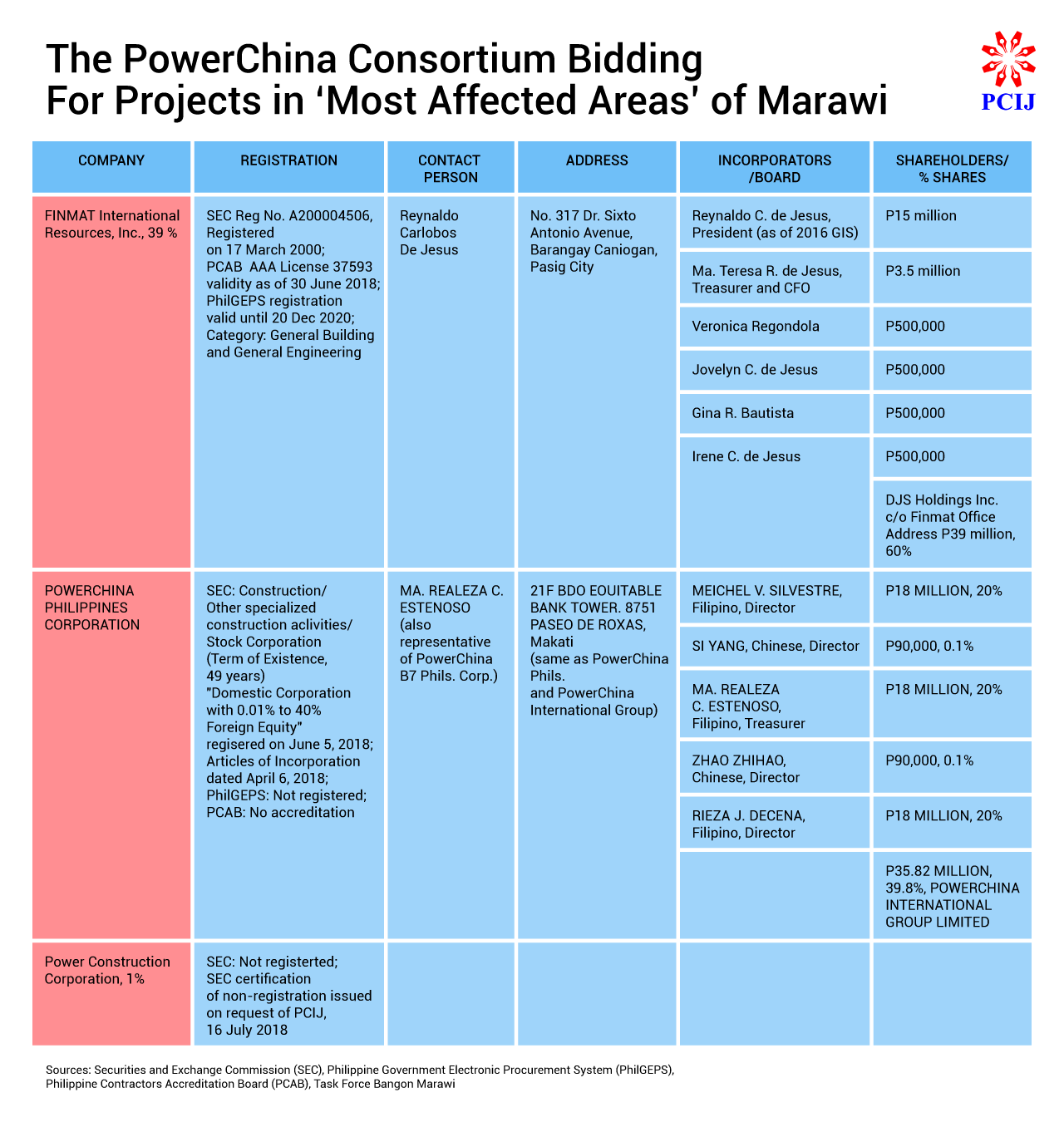

Power Construction Corporation of China Ltd. (PowerChina) — through a newly registered “domestic” firm called PowerChina Corporation of the Philippines (PCPC) — heads the new consortium that is reportedly the “second-best proponent” for the massive Marawi rehabilitation project. Initially, PCPC wanted to snare the deal for PhP19 billion or PhP3 billion more than what was put forth by the first consortium.

But which of the 331 subsidiaries and 346 branches of PowerChina, the “ultimate parent company,” is actually bidding for the rehabilitation and reconstruction projects in Marawi’s 250-hectare “conflict zone”?

The online data cloud of Dun & Bradstreet Hoovers, which “delivers the world’s most comprehensive business data and analytical insights…on 300 million business records, from more than tens of thousands sources,” even shows that PowerChina has 678 “corporate family connections” in all.

The Task Force is not clear about which PowerChina entity it is dealing with, and the documents that PCPC has submitted so far are no help either.

Last June 5, 2018, PCPC registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) as a “domestic corporation” with three Filipinos listed as incorporators and shareholders. They reportedly invested PhP18 million each, or PhP54 million in all, representing 60 percent of PCPC’s PhP90-million subscribed capital, hence its “domestic corporation” status. As taxpayers, though, the three Filipinos are classified as “employees” only.

Another 39 percent or PhP35.83 million of PCPC’s equity came from PowerChina International Group Ltd. — again a subsidiary of PowerChina the parent company — and the puny balance of 0.2 percent from two Chinese nationals, Zhao Zhihao and Si Yang, with only PhP90,000 each in equity.

PCIJ’s validation with various agencies show that PCPC was on its third week of negotiations with the TFFBM’s selection committee when it enrolled as a registered taxpayer last July 21, and when it secured its business permit from Makati city hall last July 23.

And because it has hardly started operations, PCPC is still not registered with the Philippine Government Electronic Procurement System (PhilGEPS) as a supplier, and has no license as yet from the Philippine Contractors Accreditation Board (PCAB). Documents at the SEC show its date of incorporation as April 6, 2018.

NorthRail a lesson

The folly of closing deals with subsidiaries of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) as had happened in the botched North Luzon Railways Corp. (NorthRail) project should serve the Task Force an abject lesson.

The project had run into serious trouble on many levels: the contract for Phase 1 of the project was awarded without bidding; the contract price was on the high side; the project’s scope of work was too broad and flabby; the contractor had finished only 15 percent of the project after six years and, failing in its bid to get a bigger budget for the project, decided to reduce and revise the project scope of work; the contractor is a mere subsidiary or operating unit of a China SOE.

It was in 2003 when the Arroyo administration awarded the contract without bidding to China National Machinery & Equipment Corp. (Group) or CNMEG, the firm designated by China to get the deal. The project was funded with a US$400-million loan from the Export-Import Bank of China (China Exim).

By 2010, CNMEG had accomplished only 15 percent of the NorthRail project and in the same year had changed its name to China National Machinery Industry Corp. or Sinomach.

CNMEG had sought and secured an amended contract that increased the project cost from US$421.050 Million to US$593.88 Million, and extended project completion date from February 2010 to June 2012.

Immune from suit?

Because of supposed project revisions and delays, the Aquino administration in 2012 cancelled the supply contract for the NorthRail project. Saying the cancellation was “not justified,” Beijing threatened to declare the Philippines in default of its loan and submitted the case for arbitration proceedings in Hong Kong.

In its motion for the dismissal of the case, CNMEG argued that Philippine courts “did not have jurisdiction on its person, as it was an agent of the Chinese Government, making it immune from suit, and the subject matter, as the NorthRail Project was a product of an executive agreement.”

To avoid being declared in default, however, Manila in 2012 agreed to pay Beijing installment amounts on more than half the total loan that had already been disbursed, or US$180.8 million plus annual interest of three percent. Last year, Duterte’s Cabinet members managed to settle the issue with both Manila and Beijing agreeing to mutually give up their claims on the project.

Ironically, the National Housing Authority (NHA), which will now sign for the government in the proposed contract for Marawi’s MAA rehabilitation, had also played a lead role in the NorthRail fiasco. NHA was assigned by then President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo to manage a PhP6.6-billion resettlement program for the 40,000 families from Malolos City and five towns of Bulacan who had been displaced by the NorthRail project.

Legal flaws, red flags

What happened with the failed NorthRail project should be a timely prompt for the Bangon Marawi Selection Committee (BMSW) to also scrutinize the data and documents that have been submitted by PowerChina, the second proponent consortium for the city’s MAA projects.

As it is, PCIJ’s research with various state agencies show that the “PowerChina” entity that is now bidding for the Marawi contract seems to be no better prepared or proper with its documentary submissions than the Chinese SOE leading the first consortium; neither does it seem to show more qualifications to take on the MAA project in what is the capital of Lanao del Sur.

On many counts, PCPC as an entity bears many legal flaws and posits red-flag issues. Some of its shareholders are apparent dummies. It has not registered to be a supplier of goods and services for the government. It has no track record and therefore no license as yet as a contractor. It even has a record of abandoning contracts with local corporate partners.

Too, it has had no operations as yet. Still, while it has only PhP90 million in subscribed capital by the date of its incorporation, it has proposed to roll out the Marawi MAA proposal at an initial cost of PhP19 billion — now supposedly down to P16.8 billion — via a joint-venture agreement with government.

Bank doc from Beijing

Yet, last July 25, PCPC submitted to the Task Force a number of documents, including “Proof of Successfully Undertaken Projects,” “List of Contractor’s Equipment Units,” and “Bank Certification showing available funds amounting to 605 million renminbi,” which is equivalent to about US$88.38 million or PhP4.72 billion.

Curiously, instead of securing the certification of available funds for the project from a domestic bank, as is typically required for contracts signed and sealed locally, PCPC’s certification came from a Bank of China branch in Beijing.

The Public-Private Partnership Governing Board, in its Resolution No. 2017-08-03 dated April 19, 2018, prescribed that for unsolicited proposals for projects like the Marawi MAA contract, the proponent entity must pass the following “Financial Qualification Requirements”:

* “Have (1) a Net Worth or (2) a Set-Aside Deposit, the amount of which is a significant percentage of the indicative project cost of the Unsolicited Proposal; and /or

* “Letter testimonial from one or more domestic universal/commercial banks or one or more international banks with a subsidiary/branch in the Philippines or any international bank recognized by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas ‘BSP’ attesting the financial capacity must be covered by a certification of available funds the Proponent and/or members of the Consortium (if the Proponent is a consortium) are banking with them and that they are in good financial standing, and qualified to obtain credit accommodations, the amount of which is a significant percentage of the indicative project cost of the Unsolicited Proposal.”

The PPP Resolution requires that “the sum of (i) and (ii) should be equal to the indicative project cost of the Unsolicited Proposal. In addition, the Proponent may be required to submit a Project Financing Plan, which may include the amount of equity to be infused, debt to be obtained for the project and sources of financing.”

Employees on board

The consortium of PCPC, PowerChina International Group Ltd., and FINMAT International Resources Corp. altogether have financial assets that would amount to no less than PhP150 million. This would include PCPC’s PhP90-million subscribed capital, FINMAT’s total assets of PhP43.46 million as of 2016, and the still unvalued one-percent investment of PowerChina in the consortium.

The three Filipinos on PCPC’s board — Ma. Realeza C. Estenoso, Meichel V. Silvestre, and Rieza Decena — have not assumed lead roles in the firm’s negotiations with Task Force Bangon Marawi. Instead, it is Zhao Zhihao — who introduces himself as “Jacky Zhao” — who leads the negotiations with Task Force Bangon Marawi as “the representative with authority from PowerChina.”

PCIJ was unable to find more details about two of the Filipinos on PCPC’s board. Estenoso’s digital trail, meanwhile, shows her to be an employee of Sinohydro B7 Corp., a subsidiary of PowerChina the parent SOR, is named as PCPC treasurer. PCPC’s registration papers with SEC show no other company officers; the rest of the Filipinos and Chinese in the firm are mere “directors.”

PowerChina entities, too

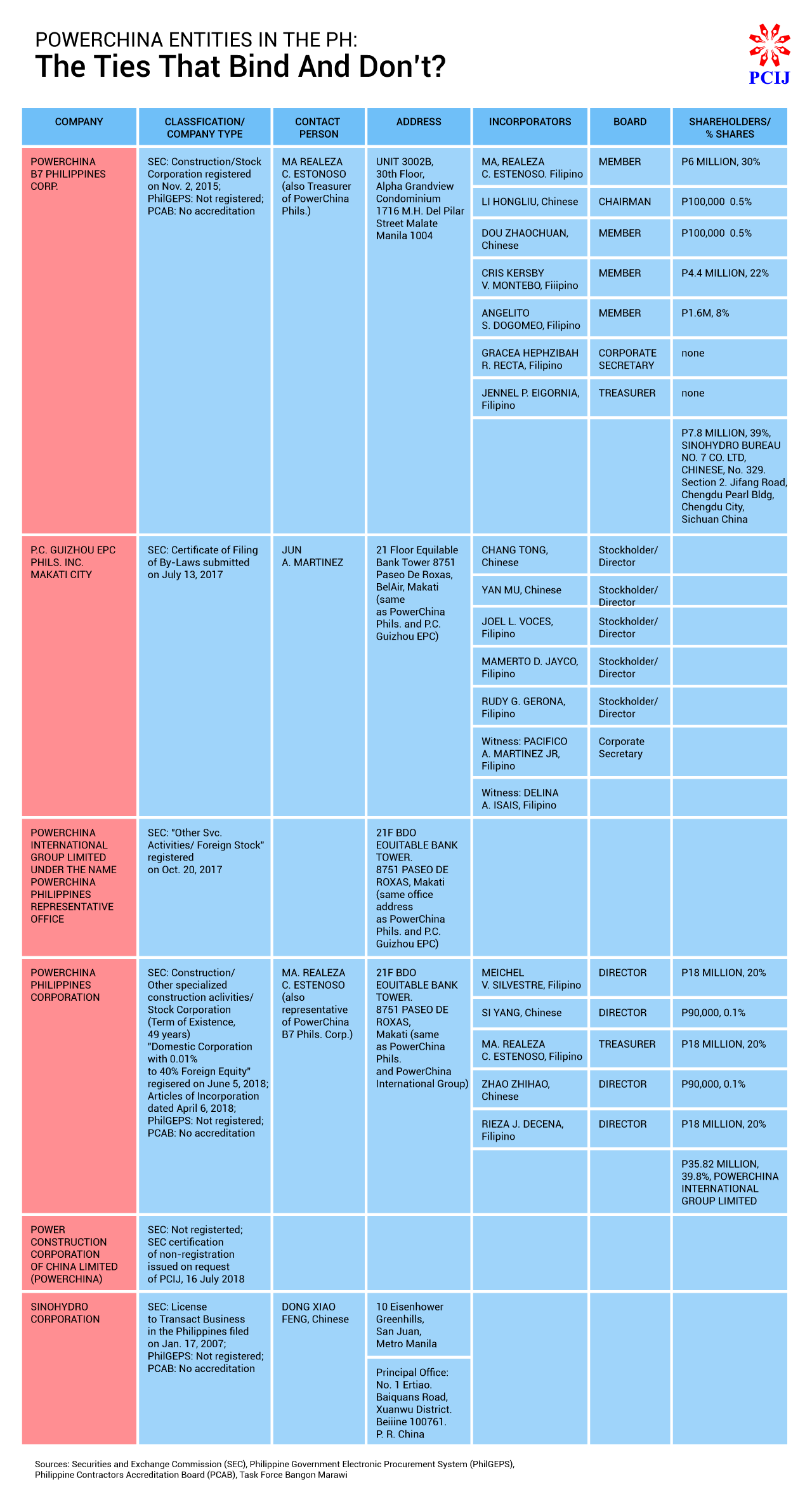

PCIJ research, however, found that at least five other entities or apparent subsidiaries of PowerChina, the parent company, have located in the Philippines since 2015.

Two entities — P.C. Guizhou EPC Phils. Inc., which registered with SEC in July 2017, and PowerChina International Group, which registered with SEC in October 2017 — hold office at the same office address of PowerChina Philippines Corp. on the 21st floor of Equitable Bank Tower, 8751 Paseo de Roxas, Bel-Air, Makati.

Another PowerChina-related entity, Powerchina B7 Philippines Corp., which registered with SEC on Nov. 2, 2015, holds office at a condominium in Malate, Manila. But what it has in common with PCPC is an incorporator and shareholder: Ma Realeza C. Estonoso.

PowerChina B7 Philippines Corp. lists Estenoso as its representative and board member with a PhP6-million investment or 30 percent of its subscribed capital of PhP40 million as of February 2016.

In the PCPC, the PowerChina entity negotiating with Task Force Bangon Marawi, Estenoso is listed as treasurer with PhP18 million in shareholdings. Her total investments in the two PowerChina entities amount to PhP24 million.

Invalid TINs

Yet another PowerChina entity, Powerchina International Group Limited, under the name Powerchina Philippines Representative Office registered with the SEC on Oct. 20, 2017 as a “foreign stock” entity for “Other Svc. Activities.”

And then there is Sinohydro Corp. — a major subsidiary of the mother SOE PowerChina — that had secured a “License to Transact Business in the Philippines” from as early as Jan. 5, 2007. At that time, Sinohydro issued a bank certification that it had deposited US$45,465.46 or PhP2,227,807 at prevailing exchange rate at a local bank.

Apart from Estenoso, two Chinese nationals — Li Hongliu and Dou Zhaochuan — and four Filipinos are listed as incorporators and shareholders of PowerChina B7 Corp. Three of the four Filipinos listed their address at Lanao del Norte, including one with subscribed capital of PhP1.6 million and another with PhP4.4 million.

But PCIJ’s check with regulatory agencies showed that two of the Filipino investors had invalid taxpayer identification numbers, while the TIN of a third Filipino investor was not updated.

In addition, the parent SOE, Power Construction Corp. of China Limited (PowerChina), is not registered with the SEC, and thus cannot not do business in the Philippines. On PCIJ’s request, the SEC issued a certificate of non-registration by PowerChina as July 16, 2018.

Not on PhilGEPS, PCAB

All apparently related subsidiaries or operating units of the parent SOE PowerChina, the six PowerChina entities in the Philippines share some more things in common: None of them is registered with the Philippine Government Electronic Procurement System (PhilGEPS) as suppliers as of August 2018. None of them has secured a license with the Philippine Contactors Accreditation Board (PCAB) as contractors, as of June 2018.

There is also no PowerChina-related firm listed in PhilGEPS list of bid and award notices from 2000 to first quarter of 2018.

According to the Housing and Urban Development Council Secretary General Falconi V. Millar, who also chairs the Task Force’s selection committee, PowerChina Philippines Corp. — as “a Filipino corporation” submitted on the last week of July one ring bond of documents, including a 45-page Proposed Draft Joint Venture Agreement, List of Contractor’s Equipment Units, and Proposed Master Plan for the Recovery, Reconstruction, and Rehabilitation Projects in the Most Affected Areas of Marawi City.

A week later, on Aug. 6, PCPC submitted its “Consortium Agreement” covering itself, representing 60-percent share in the Consortium; Power Construction, one percent; and FINMAT International Resources, Inc. (FIRI), 39 percent.

FINMAT has a Triple-A contractor accreditation with PCAB (valid from June 30, 2018 to Dec. 20, 2020), and a “Platinum” supplier registration status with PhilGEPS valid until March 24, 2019.

Reynaldo Carlobos De Jesus is president of FIRI, which began operations in February 1997 and was once registered as FINMAT Marketing.

According to the company’s website, “FINMAT was involved in marketing and small-scale projects from counter top installation to toilet tiling” and “by 1998, started to engage in architectural finishes such as drywall partition, gypsum and acoustic ceiling, and tiling works for small-scale construction.”

“The company grew by leaps and bound over the next few years; hence, in 1999 to early quarter of 2014, FINMAT became busy in the construction of commercial, offices, condominium, banks, high end residential in exclusive subdivisions and villages for a quality plumbing, glass, electrical and civil works,” company’s website added. It was during the same period that FIRI said that it was “accredited by owners/contractors such as Robinson Land Corporation, SM Land Development Corporation, SM Development Corporation, Empire East Land Holdings Inc, to name a few.”

Total assets: PhP43.56M

In 2015, FINMAT said, it was awarded the architectural and structural works for the Manila Bay Resort Project, paving the way for securing its ISO certification and PCAB accreditation.

SEC records show, however, that FINMAT registered as a stock corporation only on March 17, 2000. Its listed office address at No. 371 Dr. Sixto Antonio Avenue, Barangay Caniogan, Pasig 1606 is just a townhouse/apartment unit by make and size.

And while its accreditation and registration papers seem to be in order, whether FINMAT’s financial capacity would be sufficient to support its 39-percent share in the PowerChina-led consortium begs further evidence.

In its latest financial statement for 2016 filed with the SEC, FINMAT said it had total assets of only PhP43,556,777.

Its total paid-up capital is PhP60 million, including PhP21 million from Reynaldo de Jesus (PhP15 million) and PhP6 million combined from six other Filipino incorporators; and PhP39 million from an entity called DJS Holdings that lists as its address FINMAT’s office address.

In the last two months, online job-hunting sites show about two dozen job openings at FINMAT for civil engineers (plumbing), geodetic engineer, architect, CAD operator, electrical engineer. FINMAT reportedly has projects in Davao City and Cebu City.

Wholly state-owned

To be sure, the parent company PowerChina is a huge conglomerate. It ranked No. 182 in the 2017 Fortune’s Global 500 List, and has reportedly 186,234 total employees. Its revenues last year reached US$53.87 billion, but its profits came to only US$946.7 million, down 10.5 percent from 2016.

According to a financial outlook report posted on Wall Street Journal online, in 2017 PowerChina, a listed company, marked a decline in its capital expenditures by $73.14 billion, while its free cash flow slid by P67.3 billion. Its cash flow per share rose by a third of a percent, but its free cash flow per share went down by 4.40 percent. Wall Street Journal said that PowerChina had only 131,091 employees.

As of March 2018, the report said that PowerChina had cash and short-term investments of US$69.41 billion, a significant US$270 billion in total debt, US$487.29 billion in total liabilities, US$76.37 billion in total shareholder’s equity, and 4.86 book value per share.

PowerChina’s official website says that it is “a wholly state-owned company that was set up in September 2011 on the basis of 14 provincial/municipal/regional electric power survey and design, engineering and equipment manufacturing enterprises formerly affiliated to Sinohydro Group Ltd, HydroChina Corporation, State Grid Corporation of China, and China Southern Power Grid Company Limited.”

Two years later in 2013, PowerChina said it already “consists of Sinohydro Corporation with 32 subsidiaries, HYDROCHINA Corporation with 12 subsidiaries, China Renewable Energy Engineering Institute, 12 survey and design institutes, 23 construction companies, and 18 manufacturing and maintenance companies.”

PowerChina says that its ranks “42nd among the Top 500 Enterprises of China; fifth in the list of the world’s 250 largest global contractors, and placed second among the top 150 engineering design companies worldwide.” Its major subsidiaries Sinohydro, HydroChina, SEPCO III and SEPCO have quickly risen in the roster of the world’s top contractors and design firms, it added.

For five consecutive years, PowerChina says, it “has been evaluated as a Grade A enterprise by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council.” — With research by Karol Ilagan, PCIJ, August 2018