(First published in Sunday Inquirer magazine, December 1991. Reprinted in DABAW Journal in commemoration of Davao City’s 56th Anniversary, 1993 Edition).

In the past, Davao had been every Japanese laborer’s dream destination. Today, Japan is the dream destination of many Filipinos….

Fourteen-year old Arturo Hagio and his companions were preparing breakfast in a poultry farm in Padada, Davao del Sur, at around 6 a.m on Monday, Dec. 8, 1941, when they saw two warplanes buzzing.

DPWH personnel install the Philippine and Japan flags along JP Laurel Avenue, Davao City on Tuesday (10 January 2017) in preparation for the visit of Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on Friday. MindaNews photo

DPWH personnel install the Philippine and Japan flags along JP Laurel Avenue, Davao City on Tuesday (10 January 2017) in preparation for the visit of Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on Friday. MindaNews photo

Moments later, the earth shook as somewhere nearby two bombs exploded. The Japanese had just bombed the American ship Langley in neighboring Malalag coast.

At the Davao City High School at around 7:30 a.m., Ernesto Corcino and his schoolmates had just sung the Philippine national anthem at the flag ceremony and were about to listen to the principal’s usual Monday speech when they heard the “humming of the planes above us.”

Moments later they heard an explosion. The Davao City Airport and oil depot in Sasa had been bombed by the Japanese.

Hagio and his fellow workers at the poultry farm in Padada hurriedly ate the breakfast they had prepared. It was to be their last proper meal for the next 12 days.

At around 9 a.m. elements of the Philippine Constabulary herded them into a truck and took them to an elementary School in Davao City that had been converted into a concentration camp.

Their “crime:” they were Japanese or like Hagio, children of Japanese fathers.

While the “Hapon” all over the city and nearby towns were being herded and taken to “concentration camps” that same morning, students at the Davao City High School were being advised to go home.

Corcino and his buddies who were neither Japanese nor half-Japanese stayed on, mapping out plans on how to serve in the Philippine Army. They were underage. “but even if we were, we were enthusiastic. We wanted to fight ,” Corcino recalls.

In the next 12 days while Hagio endured lack of food and torture in a cramped concentration camp in the city, Corcino and the rest of the panic-stricken population bought up food and other provisions prior to evacuating.

At the same time, Filipino soldiers and volunteers enlisted in the army.

On December 20, 12 days after the bombing of Malalag and Davao City, cannons boomed from the Sta. Ana Wharf in the City. The Japanese Imperial Army had landed. The Dabawenyos fled to the outskirts of the city as the Japanese and nikkei-jin (descendants of Japanese) prisoners like Hagio were released by their compatriots.

In that 12-day interval between the bombing and the landing of Japanese forces in the city, the once friendly community of some 80,000 people in Davao City, around 30,000 of whom were Japanese and their children, became a hostile place.

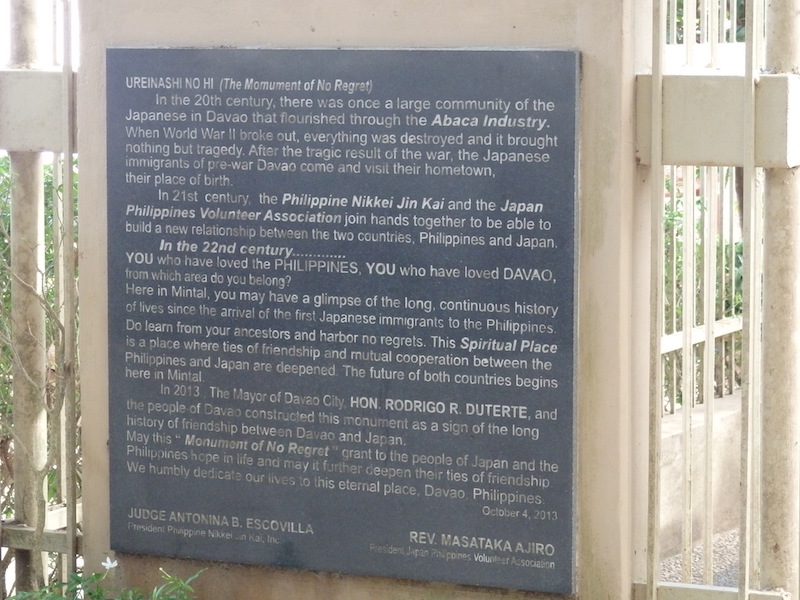

UREINASHI NO HI. The Monument of No Regret at the Mintal Cemetery in Davao City. Busloads of Japanese come here every August to visit the graves of their ancestors. MindaNews photo by Carolyn O. Arguillas

UREINASHI NO HI. The Monument of No Regret at the Mintal Cemetery in Davao City. Busloads of Japanese come here every August to visit the graves of their ancestors. MindaNews photo by Carolyn O. Arguillas

“Monument of No Regret” at Mintal Cemetery in Davao City. MindaNews photo by Carolyn O. Arguillas

“Monument of No Regret” at Mintal Cemetery in Davao City. MindaNews photo by Carolyn O. Arguillas

Before the war, the Japanese presence in Davao had continually increased-from 30 in 1903 to 1,550 in 1915 to 12,459 in 1930 and to an estimated 30,000 by 1941. The first batch of Japanese who came were laborers who had been hired by Americans to build Kennon Road in Baguio.

“Peacetime, as that period was called, saw increasing Japanese economic dominance in Davao. Japanese nationals operated abaca plantations, department stores, and other sorts of business and trading. Davao became known as “Davaokuo” and “Little Tokyo.”

“Without the Japanese who conquered the terror of the jungles in Davao in the early days, perhaps the Dabawenyos would not be enjoying the economic prosperity and would not be able to attract people from other places. It was a known fact that the development of the Davao province (then undivided), was a result of Japanese efforts,” writes Gloria Dabbay in Davao City: Its History and Progress.

President Manuel Quezon, in a visit to Davao on June 28, 1939, said: “The Japanese have developed these lands that were underdeveloped before. They have taught us how to have modern plantations. If the Philippines should take advantage of what we can from what the Japanese are doing here, the coming of Japanese to Davao, instead of being an evil, would be a blessing for the Filipinos.”

But it was Quezon himself, mainly out of concern over the “Japanese problem,” who engineered the creation of the City of Davao, the bill which he signed on Oct. 16, 1936.

“The motive for the creation of the City of Davao was the presence in Davao and Guianga of many Japanese nationals. It was then feared that through elections the Japanese would be in a position to control Davao and Guianga,” wrote Assemblyman Romualdo Quimpo, author of the bill to whom Quezon intimated the idea of creating a city of Davao.

The Japanese of Davao, having become an economic power, were thus capable of controlling political power. By this time, they had felled virgin forests to give way to agricultural ventures and were operating at least 65 plantations ranging in size from 100 to 1,024 hectares.

Government officials feared incurring the displeasure of the Japanese and thus losing their patronage and friendship.

The Ohta Memorial within the compound of the Mintal Elementary School in Davao City is in honor of Ohta Kyozaburo, the Japanese entrepreneur who first set up abaca plantations in the city in the early 1900s. MindaNews photo by Carolyn O. Arguillas

The Ohta Memorial within the compound of the Mintal Elementary School in Davao City is in honor of Ohta Kyozaburo, the Japanese entrepreneur who first set up abaca plantations in the city in the early 1900s. MindaNews photo by Carolyn O. Arguillas

“Japanese interests in Mindanao have great influence upon the people (here) particularly those in the government and the higher-ups in Mindanao, especially Davao. To the lawyers, the Japanese elements are the best clients, to the doctor they are the best patients, to the public officials they are the best friends, especially when the Christmas time comes, “wrote Pantaleon Pelayo Sr., a delegate to the 1934 Constitutional Convention who was mayor of Davao City at the outbreak of World War II.

The war would change the face of Davao and the Filipino’s regard for the Japanese would turn from a “blessing” to an “evil.” The war, too, would show that quite a number of Japanese business executives who settled in Davao in the 1930s were in reality military majors and colonels.

Recalls 78-year old Mariano Pamintuan, owner of the Apo View Hotel, of that period: “ I classified the Japanese as good and bad. There were some good ones but the bad ones were really bad.”

Mayor (Pantaleon) Pelayo (Sr.) wouldn’t allow us to evacuate. He kept saying `we can defend Davao against the Japanese, but there were only 150 Philippine Constabulary elements then, 700 Filipino trainees without guns and about five American soldiers led by Colonel Hillman,” recalls Pamintuan. The Japanese forces that landed in Davao were estimated to number 12,000.

“I didn’t believe Davao could be defended at all. I told my wife we’d better get out here” Pamintuan says. Elsewhere, entire families were being massacred. “The Japanese killed 5,000 to 6,000 when they first landed. When they came, they raped the nurses, including the married ones. A number of women were raped in their houses, in front of their husbands,” he adds.

Pamintuan evacuated his family to Kidapawan in what is now North Cotabato. The Japanese took over his 20 hectare land in Libby, Toril, Davao City, destroyed his house and converted the area into a landing field.

Corcino, now 69 and an adviser of the Davao Historical Society, says the leaders of the Volunteer Guards who rounded up the Japanese and mestizos at the start of the war were among the first to be killed.

“Some Volunteer Guards also raped the wives of the Japanese when they herded them into concentration camps. The victims reported the perpetrators to the Japanese Imperial Army, who then looked for these Volunteer Guards and killed them, he adds. Among those killed were Filipinos who had earned the hatred of the Japanese due to land conflicts.

But the Japanese committed their worst atrocities, recalls Pamintuan, when they learned that the Americans were coming. “Yamashita ordered Japanese units to kill any Filipino behind Japanese lines.”

The same may be said of Filipino guerrillas. Dabbay notes that when the American Liberation Forces headed by Major General Woodruff arrived in Davao on May 2, 1945, the people were overcome with both joy and fear. “There was joy because the people were once again free to move about and fear because of the “barbaric acts” shown by some Filipino guerillas who in their anger against the abusive Japanese soldiers turned their ire on the captured Japanese soldiers until the American Liberation Forces imposed discipline.”

Japanese-owned plantations were confiscated by the government and taken over by Filipino soldiers and guerillas.

Hagio, who returned to Digos, Davao del Sur, after his release from prison on December 23, 1941, could no longer locate his mother, brothers and sisters. He worked for the Japanese forces as a utility boy or as laborer in the construction of an airfield.

When the Americans started bombing operations in 1944, he and the Japanese fled to Mt. Apo. The following year, a sickly Hagio was left behind by the Japanese troops. He says he was captured by black Americans who took him to a dispensary for treatment.

Because Hagio was known to have worked with the Japanese forces, Filipino guerrillas went after his head. He fled to Samal Island across the city, where for next eight years he lived with an elderly Muslim couple who adopted him. Hagio says he had to learn the dialect because having finished the elementary grades in a Japanese School in Digos, he knew only Nippongo.

“There were at least 12 Japanese schools in Davao before the war.” he says. his father, Hagio Sampe of Kumamoto, who died in 1939, belonged to the third wave of sakadas brought to Davao.

In 1954, Hagio went back to Digos but moved from one town to another because he was still “wanted” by the Filipino guerrillas.

Rodolfo Tutor, Pedro Madum, Felisa Baltazar and thousands of others to this day bear the family names of their mothers. They carry their Japanese fathers’ last names as their middle name. The use of maternal family name was meant to protect the children from harm.

Even that, however, did not guarantee protection.

Tutor, who was three months old when the war began, recalls growing up with his mother, a Bagobo native, who scolded and spanked his older brothers for speaking, writing and acting Japanese. Rodolfo was the third of four children. His older brothers attended a Japanese school before the war. After the war, their mother did everything she could to de-Japanize her children for security reasons.

“Masuwerte ako noon kung wala akong bukol galing sa eskuwela,” Tutor says. “Our classmates would throw stones at us or shout ‘anak sa Hapon, anak sa Hapon’.”

He was fortunate that years later, he was reunited with his father who had separated from his mother in 1945.

Adelaida Panaguiton (nee Sakai), 51 does not know where his father is.

Felisa Baltazar last saw his father, Fukoda Masao, on Dec 8, 1941 when the Philippine Constabulary put him on a truck. She recalls having engaged in fistfights after the war, even with male classmates who would taunt her with shouts of “Hapon, Hapon”. In 1974 she learned that her father had died in Japan in 1972.

Pedro Madum of Tagum, Davao del Norte, never went to school because “hadlok mi sa Pilipino” (we were afraid of the Filipinos). His father, Kajoka Bumkichi, was a building contractor who married Maria Madum, a Mansaka native. Kajoka wanted to enroll his son in a Japanese school in Calinan before the war but his mother thought it was too far. Mag-ugpo (now Tagum) was still forest land then.

Madum remembers the last time he saw his father. They were on the banks of the Hijo River, his father in a banca bound for Davao City and he and his mother in another boat bound for Magdum

The forest of Agusan provided them refuge during the war. They went back to Tagum after the war but Madum was not sent to school either. He could not even linger outside their house because stones were being thrown at the “anak ng Hapon.”

In the ’60 and ‘70s, several attempts were made to organize the sons and daughters of Japanese fathers in Davao. In 1979, Hagio met Rev. Keizo Miyamoto of the church of World Messianity who advised him and several other second- generation Japanese in Davao to set up the Philippine Nikkei-jin Kai. Today, the Philippine Nikkei-jin Kai in Davao has 10 chapters nationwide with at least 7,000 registered members in Davao.

Over time the Japanese fear of reprisal from Filipinos has subsided. The sons and daughters of Japanese no longer have to lose sleep over stone throwing incidents and fistfights.

Fifty years after the war, Japan has become the recognized economic power of the world. And the cursed, hunted and hated Japanese descendants in the Philippines are becoming objects of envy. Again.

In the past, Davao had been every Japanese laborer’s dream destination. Today, Japan is the dream destination of any Filipinos. And the Nikkei-jin are being envied allegedly because their lineage would ensure them priority in job placements there.

Such, however, is not the case.

Daily, at the Philippine Nikkei-jin Kai office, the sons and daughters of Japanese fathers come to register for membership and to avail themselves of services such as checking with the Japanese government whether they were registered by their fathers in Japan, late registration of their births to Japanese fathers and assistance with job placements in Japan for their sons and daughters.

The process is the tedious one. Baltazar wants her son to work in Japan because of “kawad-on” (poverty) here. Her papers have to be processed. Are there records in Japan to prove she was acknowledged by her Japanese father at al? Lacking that, how can her son prove he is a grandchild of a Japanese?

Hagio, Tutor, and Madum say the Japanese government should not make life any more difficult for them. “It’s as if we’re being taken for granted, “ Hagio says, adding that while they lived comfortable lives in Davao prior to the war, “after the war our properties were confiscated. We were left with nothing. If it were not for the Japanese government’s craziness then, we would not be suffering now.”

Second-generation Japanese like them have organized to ask the Japanese government “to give what is due us and pay the claims of those who extended assistance to the Japanese Imperial Army.” Tutor explained.

Third-generation Japanese like Baltazar’s son wants to go to Japan to work.

The scenario is a familiar one.

Almost 90 years ago, their Japanese grandfathers came to Davao to find jobs.

(First published in Sunday Inquirer magazine, December 1991. Reprinted under the title “Windows to Japan’s Past” in DABAW Journal in commemoration of Davao City’s 56th Anniversary, 1993 Edition — a project of the Executive Committee of Araw ng Dabaw composed of the government sector represented by the City Mayor’s Office and the private sector represented by John Y. Gaisano, Jr. of JS Gaisano Inc.)