DAVAO CITY (MindaNews/05 December)– “We cannot stop a storm but vulnerability is something we can address.”

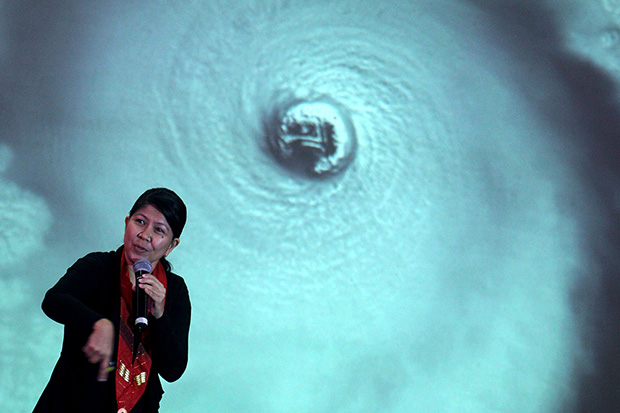

Dr. Gemma Narisma, head of the Regional Climate Systems program of the Manila Observatory, shows the satellite image of super typhoon Yolanda during the fourm with the members of the CODE-NGO in Davao City on Thursday. MindaNews photo by Keith Bacongc

Dr. Gemma Narisma, head of the Regional Climate Systems program of the Manila Observatory, shows the satellite image of super typhoon Yolanda during the fourm with the members of the CODE-NGO in Davao City on Thursday. MindaNews photo by Keith Bacongc

This was the key message of Dr. Gemma Teresa Narisma, head of the Regional Climate Systems Program of the Manila Observatory, to members of non-government organizations from different parts of the country that are into disaster risk reduction programs.

In a forum with members of the Caucus of Development NGO Networks (CODE-NGO) here on Thursday, Narisma explained in her presentation the vulnerability of the country to typhoons.

“When you have a hazard, does it necessarily translate immediately into a disaster? This is challenge for us, or do we just sit and say: It’s going to be a disaster, it’s the strongest typhoon. Do we accept that is already the case?” she asked.

The scientist quoted a definition of disaster by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent societies, which says: “A disaster occurs when a hazard impacts on vulnerable people.”

“When you have a strong hazard, you are vulnerable, then you have a recipe for disaster. What this means is that vulnerability is in our hands,” Narisma added.

By addressing the vulnerability, she explained, the impacts could be decreased as well as the possibility of a disaster.

She called on the need to invest in education or literacy to reduce vulnerability.

Narisma also cited a study of the United Nations University for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS), which revealed that the Philippines ranked third in the 2013 World Risk Index.

The report stated that the Pacific Island nation of Vanuatu topped the chart, followed by the Polynesian state of Tonga.

In 2011, Cyclone Yasi, which was classified as a Category 5 severe tropical cyclone, hit Australia and the nearby islands in the Pacific, but only one casualty was recorded, apparently brought by addressing vulnerability, she said.

Yasi’s wrath was compared to super typhoon Yolanda that killed at least 6,000 people and typhoon Pablo with at least a thousand dead.

“How are we vulnerable? We are vulnerable if the public infrastructure is not in place—if you don’t have good water and sanitation systems, and so on. If there is a lot of poverty and housing conditions are not good,” Narisma noted.

“We are vulnerable if you don’t have don’t have good governance. If there is no good governance, we lose that coping capacity,” she added.

Narisma stressed that most victims of natural disasters are those living in poverty.

“It showed during Pablo, it showed during Yolanda. The poorer people were the most vulnerable,” she said.

When super typhoon Yolanda hit Tacloban City in the Visayas in November 8 last year, many of the casualties were from the urban poor settlement in the coastal areas, Narisma recalled.

Uncertainty of typhoons

Even as the country sits right in the active typhoon corridor, Narisma admitted that of all the phenomena associated with climate change, typhoons are actually the most uncertain.

“Will there be another Yolanda in the future? Even now I’ve heard people saying Hagupit (typhoon Ruby) is stronger than Yolanda. The answer is no. It’s not as strong as of the moment although it’s very uncertain. Over the sea it might be a Category 5 but it might slow down,” she explained.

Citing studies, Narisma said the intensities of the typhoons are getting stronger, with the most destructive tropical cyclones happening in the 1980s to 2000s.

She admitted that the studies “are not conclusive” and that she could not tell if typhoons will become more intense in the next 20 to 30 years.

But we really need to be prepared because we are in the active corridor of tropical cyclones, Narisma said.