DAVAO CITY (MindaNews / 22 August) — In the early months of the COVID-19 lockdown, a group of people talked about replicating a barter system that had become popular in Iloilo City. Stay-at-home mom Kiara Nanali and others initiated the Davao Barter Community (Official) or DBCO Facebook page and planted the seeds of a phenomenon that would soon grow into a curious and contagious happy epidemic of green thumbs. Nanali insisted on the “Official” tag, as there were offshoots to the barter group that were similarly named.

The DBCO currently has a following of 175,000 members, a growing membership that began as an alternative economy back in the first half of the pandemic. In May, Davao City was barely two months under lockdown: community quarantine (CQ) starting mid-March, an enhanced community quarantine or ECQ from April 4 to May 15, General Community Quarantine (GCQ) from May 16 until June 30 and Modified GCQ (MGCQ) from July 1.

Davao Barter Community (Official) page

Davao Barter Community (Official) page

“The DCBO started on May 22 and was created by fellow group admin Ianne Calatrava-Valenzuela,” Nanali told MindaNews. The idea came from Valenzuela’s brother Ivan, who is based in Iloilo. In Iloilo, the phenomenon was widespread, and so inspired by this, the Calatravas gathered friends to manage a Facebook group. “We really did not expect for the group to grow so fast,” Nanali said.

The barter phenomenon began as a response to a halt from normalcy.

No one could go to malls and could barely order goods online, with flight suspensions immediately affecting freight services. Travel was restricted to essential goods and errands. Non-perishable items were in the lower rung in the hierarchy of needs. Starting March, and urged by the City Government, the only malling that people were doing was buying from wet market products sold via trisikad or buying essential items like medicines.

“We wanted to help people during the pandemic, people who had limited access to cash or dili ganahan mugunit ug kwarta kay nahadlok sa COVID” (or were afraid to use money for fear of getting infected with COVID), Nanali said. And then people realized that they were trapped in their own clutter: someone’s trash is another one’s treasure.

Eventually, the DCBO evolved much like an organism. Membership grew in the thousands, almost overnight. The barter community itself began to have a discipline committee, an online persona called the DCBO principal who calls out and in the worst cases, bans unruly members.

Patterns emerged. The barters started with stuff like shoes and barely used bags. There were those who started trading in their clothes for vegetables, meat, and eggs. SPAM meat loaf became gold, with people either using the bunker food as currency for things like, of all things, pillows and bedsheets. Artworks, too, were a source of appliances. Someone is actually still systematically trading off her clutter online to build a pandemic shelter. Three months into the barter, she is still into it. This lady exchanged some of her expensive stuff for an entire unused container van.

And then came the plant barters.

Plantitos, Plantitas, Halamoms

As FB group admins, Nanali and company found that people were trading cheaper plants like snake plants and caladiums. Much pricier flora include fiddle leaf figs, rubber plants, and the elusive monstera deliciosa. Bonsai artists got as much as P80,000 in goods. There were Plantitos and Plantitas (the term an endearment to plant uncles and aunts). Halamoms (from halaman or plant) also became a buzzword for plant parents, Nanali said, but this was too gender-limiting.

Bartering plants for chicken and eggs via Davao Barter Community (Official)

Bartering plants for chicken and eggs via Davao Barter Community (Official)

Naturally, some human pests began to emerge, with one Plantita complaining she was duped by a seller for trading in P2,500 worth of goods for an unhealthy monstera cutting. The alleged duper was investigated by the DCBO Principal and could face the horror of the social media block, which means he or she may no longer see the group on Facebook (much less transact). But the latest update is the seller had reached out to the buyer, they have exchanged their bygones, and all is well.

Up until 2020, the idea of a massive greening “revolution” in Davao City was more or less put in the backburner of development ideas, if not ignored altogether. The City Agriculturist’s Office (CAO), for example, had advocated for urban container gardening as early as 2016, at the start of Mayor Sara Duterte’s return to the mayoralty. It was part of her Byaheng Do30 agenda, months before the repetitive catchy tune played between her pandemic briefings aired by the local government unit-owned Davao City Disaster Radio.

Dabawenyos were encouraged to plant their own vegetables, with the CAO providing free seeds. Aside from inter-office contests, the gardening fad didn’t catch on as widely, pre-COVID-19.

In previous administrations, the City Environment and Natural Resources Office also pushed for the use of bokashi technology, which accelerates decomposition and “cleans up” organic matter such as canals through microorganisms. The idea did not see the light of day, despite plans of deploying the things along Roxas canal. Think of the canal parallel to the Roxas Night Market full of living, swimming fish.

There were also plans to “green” the Davao River and nearby bodies of water through the use of vertical helophyte technology to filter sediments and clean up the river and bucana water. Every business is required to put up water catchments, but with floods lately still spilling into homes this year, no one is sure if this is having the desired effect.

But the plant traders may be on to something.

Return on Investment

Davao City-based Architect Ryan Songcayauon told MindaNews that policymakers could capitalize on the phenomenon. It was, after all, peculiar for the pandemic to result in the popularity of plant trades. Songcayauon, who teaches at the University of the Philippines-Mindanao, said the emerging economic value could benefit the city in the long run.

“Usually, when you say environment and greening, people just shrug it off and move on to other more important matters,” he said. There was, after all, no immediate return on investment (ROI) to be had. But according to Songcayauon, cleaner air was ROI enough.

A man wearing a surgical mask crosses the intersection of San Pedro and CM Recto Streets in Davao City on 16 March 2020 when Davao City was placed under community quarantine amid threats of COVID-19 infection. MindaNews photo by MANMAN DEJETO

A man wearing a surgical mask crosses the intersection of San Pedro and CM Recto Streets in Davao City on 16 March 2020 when Davao City was placed under community quarantine amid threats of COVID-19 infection. MindaNews photo by MANMAN DEJETO

The April 2020 readings at the Environmental Management Bureau showed that since the start of the ECQ, there has been a dip in detected particulate matter in the air. The data is based on readings from various meters around the city. Simply put, with no industries operating during the lockdown, and almost no vehicle emissions, the city’s existing greenery could finally catch up. Urban areas like Metro Manila began seeing mountain ranges as far as the Sierra Madre during this time. There were stars at night. In Davao City, the air was cleaner than before, even in areas such as the Panacan industrial zone and the Davao International Airport. But the Davao-based architect said this was, surprisingly, not the answer we were looking for. There has to be more.

“We can’t expect a full on pandemic scenario as the answer,” he said. “It has to be sustainable.”

GUHeat

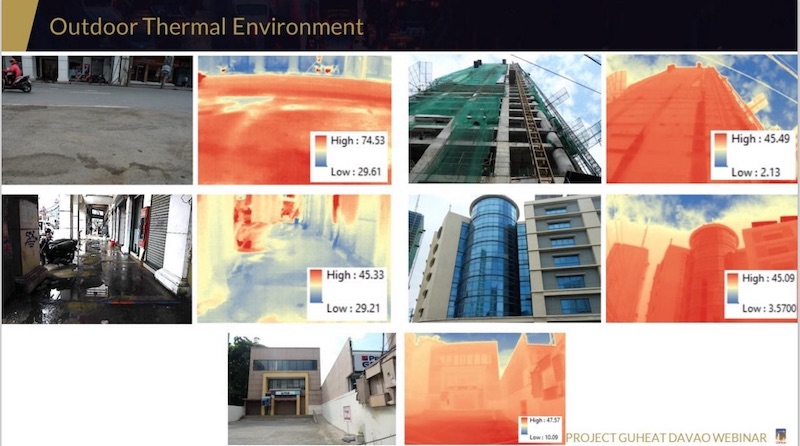

Songcayauon was one of the speakers during the Davao City leg of the Project GUHeat talks, as a representative from academe. The talk compiled in a three-hour zoominar the results of several studies held in Davao City, while the other webinar legs focused on other key cities. The Davao studies included geographical information system (GIS)-based simulations of the effect of structures to the temperature of major areas here.

Project GUHeat sample readings of outdoor thermal environment. Courtesy of Project GUHeat

Project GUHeat sample readings of outdoor thermal environment. Courtesy of Project GUHeat

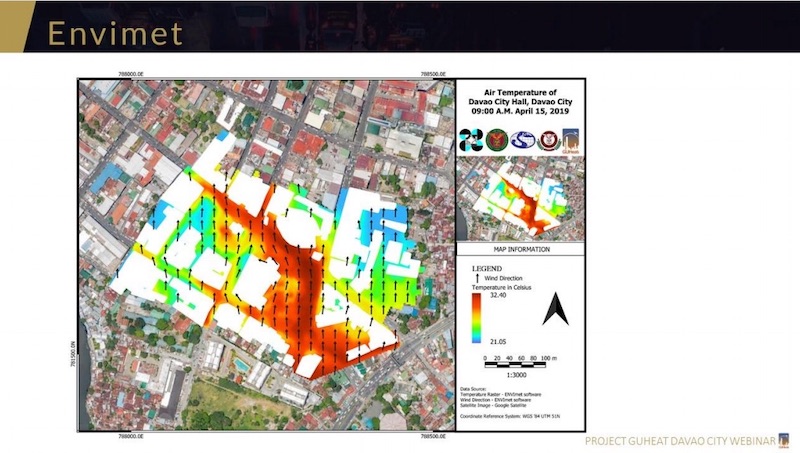

GUHeat stands for “Geospatial Assessment and Modelling of Urban Heat Islands (UHIs) in Philippine Cities.” Simply put, satellite images, as well as ground studies draw up data-based simulations of urban heat that’s understandable to local policymakers through maps and 3D illustrations, aside from the scientific research that spells out the entire process.

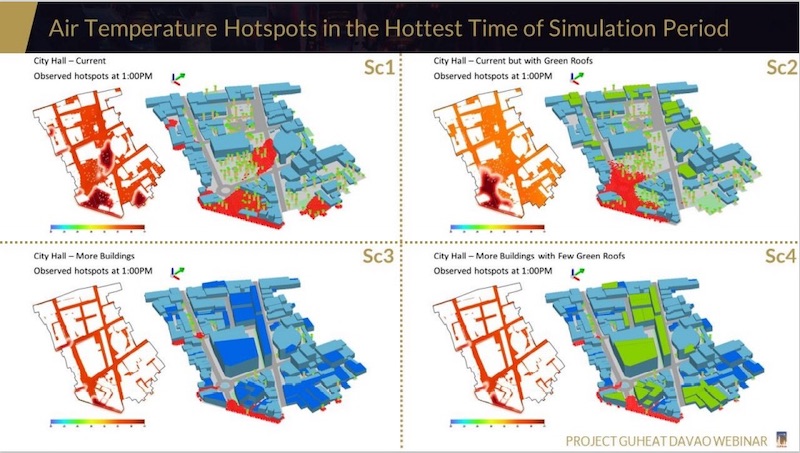

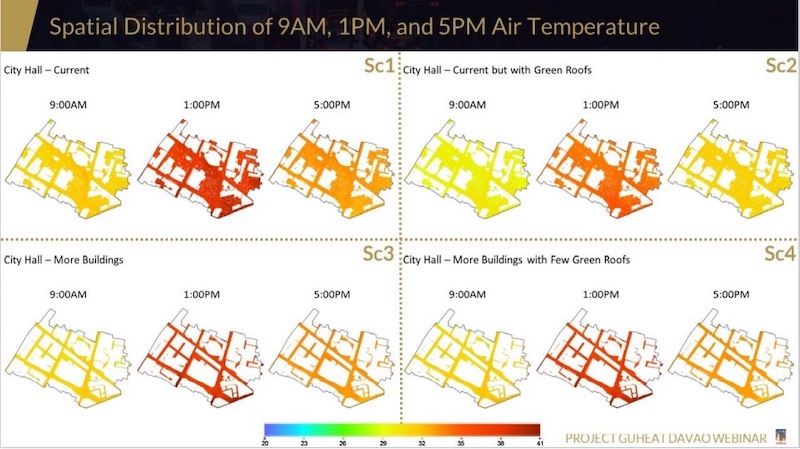

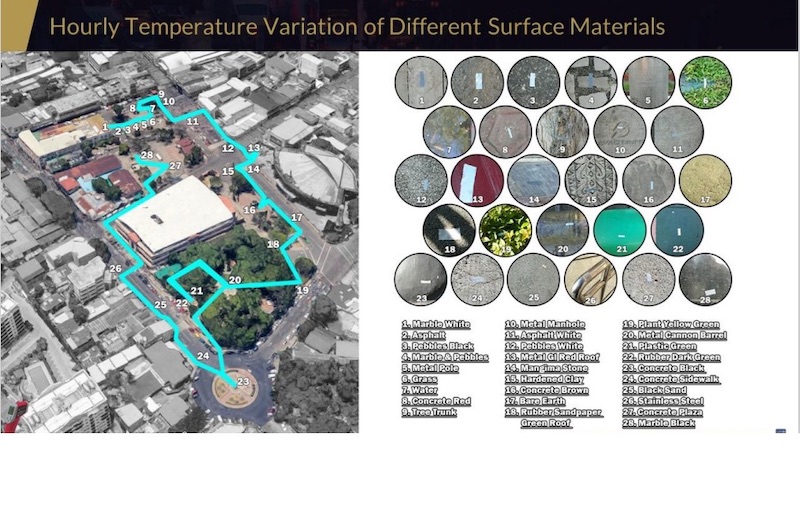

For example, the heat in and around the City Hall Building and its surrounding structures as well as the effects of heat to areas such as CM Recto Street (referred to in the study by its old and more popular name ‘Claveria’). Notable among the findings is the effect on rooftop greenings around these areas to surface and air temperature. The scientists even catalogued materials like pole metals and paver bricks, among others, and calculated their contribution to the average temperature of the area at different times. Scientists simulated the effect of greening Davao City’s downtown buildings and taking note of its effects on surface heat (the heat that bounces off roads and other materials closer to buildings) and air temperature.

Observed hotspots around the Davao City Hall grounds in different simulations. Courtesy of Project GUHeat

Observed hotspots around the Davao City Hall grounds in different simulations. Courtesy of Project GUHeat

Simply put, the combination of materials used around the city’s urban centers as well as a lack of greenery contributed greatly in the heating of several areas here, notably the downtown and Claveria zones. Notable, too, is the effect of structures sandwiching natural airways and creating heat canyons because of the interplay of arrangements of buildings, the roads as partitions, and the lack of flora along downtown streets such as Claveria.

Sample reading of the air temperature around Davao CIty Hall in 2019. Courtesy of Project GUHeat

Sample reading of the air temperature around Davao CIty Hall in 2019. Courtesy of Project GUHeat

Project GUHeat “aims to assess the development of urban heat islands in rapidly urbanizing and highly urbanized cities in the Philippines and develop models for estimating land surface temperatures (LST) and predicting UHIs by relating LST with environmental factors including land use land cover distribution,” according to its Facebook page.

Greenery in and around City Hall

GUHeat is a series of studies in key cities around the Philippines measuring the interplay between development in urban areas and their direct effect on temperature, pollution, comfort, and essentially, the health of its citizens.

Sample simulations of Davao City Hall grounds show it is usually hottest at around 1 p.m. Courtesy of Project GUHeat

Sample simulations of Davao City Hall grounds show it is usually hottest at around 1 p.m. Courtesy of Project GUHeat

The project is run through the Department of Science and Technology, the Philippine Council for Industry, Energy, and Emerging Technology Research and Development and the University of the Philippines-Training Center for Applied Geodesy and Photogrammetry.

In architecture and construction, the phenomenon of urban heat islands is basically the effect of urban development on temperature and pollution. Seen from the sky, cities like Davao appear like greying scabs over the much greener portions of undeveloped land, and perhaps tellingly.

The studies under GUHeat aim to “minimize the warming of urban areas or UHIs, and even reverse it to decrease electricity consumption and air pollution, reduce health risks and diseases, that will result to greater livability of… cities.” Among the outputs are user-friendly GIS models of the results of the studies.

Part of the Davao City simulations mapped out sample materials that contribute to surface heat in places like the Quezon Park along Magallanes. Courtesy of Project GUHeat

Part of the Davao City simulations mapped out sample materials that contribute to surface heat in places like the Quezon Park along Magallanes. Courtesy of Project GUHeat

For Davao City, GUHeat has several suggestions. Among these are the encouragement of greenery in and around areas like the City Hall and streets like Claveria. Surprisingly, there were also times when areas such as the People’s Park, despite its greenery, recorded peak heat of around 40 to 50 degrees Celsius.

44% dip in pollutants

Data from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources’ Environmental Management Bureau in the Davao region showed that for the first quarter this year, there were dips in pollutants in the city’s airshed, compared with the previous period in 2019.

For some weeks in April 2020, for example, readings for particulate matters less than 10 microns and less than 2.5 microns were lower by 44% for PM10s and around 20% for PM2.5s. Particulate matters are microscopic substances scientifically identified as detrimental to human lungs, along with dangerous levels of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, ground level ozone, and a substance called benzene, toluene and P-xylene (or BTX).

The main entrance for departures at the Davao International Airport in Davao City on 16 March 2020. Flights to and from Manila were suspended as travel to and from Metro Manila by land, sea, and air was suspended effective March 15, to prevent the spread of COVID-19. MindaNews photo by MANMAN DEJETO

The main entrance for departures at the Davao International Airport in Davao City on 16 March 2020. Flights to and from Manila were suspended as travel to and from Metro Manila by land, sea, and air was suspended effective March 15, to prevent the spread of COVID-19. MindaNews photo by MANMAN DEJETO

The 44% dip came from the reading at the Davao International Airport meter, a part of the Davao City air quality monitoring network or AQMN. The AQMN is a network of meters from different locations in the city. While both readings for 2020 (41 PM10s) and 2019 (23 PM10s) were well within the 50 reading for “Good” air quality, scientists and researchers during the GUHeat webinar agree that the pandemic era readings were around ideal, but economically unsustainable.

Real-time air quality monitoring

If environmental groups had their way, there would be a real-time meter that people could see in public areas such as parks. That way, citizens would know what they were inhaling if they roam around the city (at least during pre-pandemic scenarios).

Chinkie Pelino-Golle, executive director at Interfacing Development Interventions for Sustainability (IDIS), has some suggestions.

“The people should know the quality of air that we are breathing while we are there,” Golle told MindaNews.

Chinkie Golle’s garden at home. Photo courtesy of Chinkie Golle

Chinkie Golle’s garden at home. Photo courtesy of Chinkie Golle

IDIS has been pushing for various green ridge-to-reef policies to the local government to help address air and water pollution, as well as issues such as flooding.

In 2015, IDIS was among those who tried to fight the passage of an ordinance removing a requirement for property developers to allocate 10% of their properties as open spaces.

The City Council and a Rodrigo Duterte-era City Hall almost got into a policy tug of war, after the legislative body led by his son, Vice Mayor Paolo Duterte, passed the ordinance months before the elder Duterte would occupy the seat of power in Malacanang. Duterte promptly vetoed the ordinance, one of his last acts as Davao City Mayor, citing several portions of the amendment were beyond the City Council’s powers.

Duterte’s daughter Sara, who succeeded him as mayor in 2010 after he completed his second nine-year reign as Mayor, and who again succeeded him in 2016 and got reelected in 2019, is injecting green plans for the update of the city’s Comprehensive Land Use Plan. Sara’s own battlecry for Davao City became Davao City: Life is Here, ostensibly breast-beating a quality of life with a boost on environmental policy.

Davao City will be increasing its green space requirement for land developers from 10% to 15%. Courtesy of City Planning and Development Office

Davao City will be increasing its green space requirement for land developers from 10% to 15%. Courtesy of City Planning and Development Office

Ivan Cortez, officer-in-charge at the City Planning and Development Office said the city was even pushing for an increase of open spaces for future developers, from the 10% in the current CLUP to a proposed 15%.

As early as 2017, Mayor Sara had called for the development of more parks and green open spaces, including the development of a skate park in Agdao, a botanical garden in Marfori, and an open space at the Sta. Ana Wharf for rest and exercise.

Greening structures

Architects like Songcayauon continue to preach greening designs, attesting to the effect of plants to urban areas. He adds that greening isn’t even exclusive to plants. Establishments could push for alternative passive airconditioning systems made of intricate water cooling instead of more expensive centralized airconditioning. Homes could also invest in vents and insulations instead.

To architects like him, air conditioning contributes ironically to UHI effects. Because urban spaces are hot, people’s investments in airconditioning units have the terrible effect to cities: they contribute to the heat. Alongside other emissions, these combine to form the UHI phenomenon.

Asked what it would take for homes and structures to be much cooler in urban areas, the architect has ideas. “If we go back to the indigenous practice of using thatches and weavings for roofs, this would cool the homes,” he said, half-jokingly. The Philippine Building and Fire Codes, after all, discourage this, as there are flammability ratings to consider. Urban homes consider design; and while thatches may look “good,” they don’t do well with larger urban setups, not to mention the need to replace these every three years.

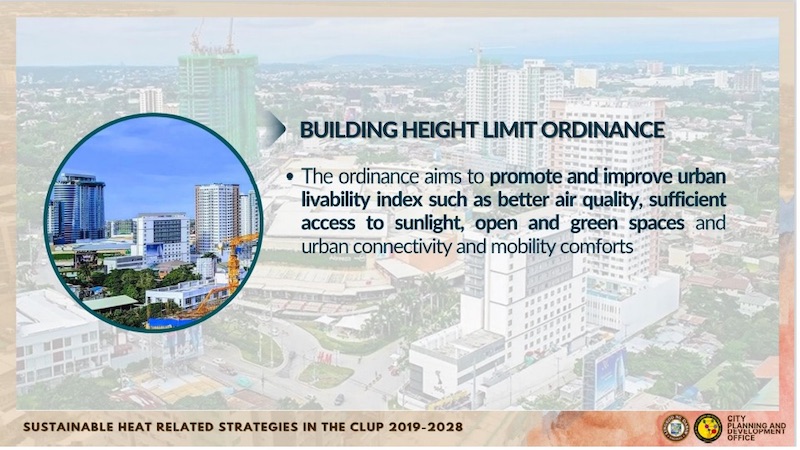

Among Davao City’s plans is to limit building heights to a maximum of 100 meters above mean sea level. Courtesy of the CIty Planning and Development Office

Among Davao City’s plans is to limit building heights to a maximum of 100 meters above mean sea level. Courtesy of the CIty Planning and Development Office

But greening structures is simple: replace the building footprint with a roofing or canopy covered with plants. In taller structures, the GUHeat study suggests vertical plant systems, as there are apparently height limits where plants may have a direct effect on cooling surface temperature. Cooler structures lead to cooler interiors, thus no more need for detrimental solutions to cool down residents. Cortez said the city will again push for a building height limit for the city as part of its policy directions. Cortez told MindaNews the city’s proposed limit is around 100 meters above mean sea level, which means building heights depend on their location in the city.

Deal!

At the DCBO page, the plants are still being bartered even with fewer restrictions on travel and the gradual transition into a new normal. But short of another lockdown, stakeholders for greening the city say that the April scenario cannot be replicated anymore unless the city adjusts with greener policies.

The city is taking baby steps, finally encouraging the use of bicycles and painting bike lanes towards both directions of the city’s major areas.

An employee of the Southern Philippines Medical Center, the designated Covid-19 hospital for Davao City, rides a bicycle on 15 April 2020. In early June, the city government finally started implementing its 10-year old bicycle ordinance by providing bike lanes in designated areas. MindaNews photo by MANMAN DEJETO

An employee of the Southern Philippines Medical Center, the designated Covid-19 hospital for Davao City, rides a bicycle on 15 April 2020. In early June, the city government finally started implementing its 10-year old bicycle ordinance by providing bike lanes in designated areas. MindaNews photo by MANMAN DEJETO

At the prodding of bike advocates and environmental groups, the city government worked on finally implementing Ordinance 0409-10 or the Bicycle Ordinance of Davao City which was signed by then mayor Rodrigo Duterte in 2010 after years of advocacy by environmentalists and bicycle groups. The presiding officer of the City Council that passed the ordinance was Duterte’s daughter Sara, then Vice Mayor.

The order to provide bike lanes in the city in early June preceded the announcement of the Department of Transportation to set up bike lanes along EDSA in Metro Manila.

Mayor Sara also waived, through an executive order, any registration fees for bike users, at least until after the pandemic.

With an ROI of cleaner air, stakeholders might as well use a popular DCBO battlecry after a successful negotiation: DEAL!

(Yas D. Ocampo / MindaNews. The production of this special report was made possible with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network)