KIDAPAWAN CITY (MindaNews / 20 December)—The other day I sold vegetables during an art exhibit, and it was sold out on opening day.

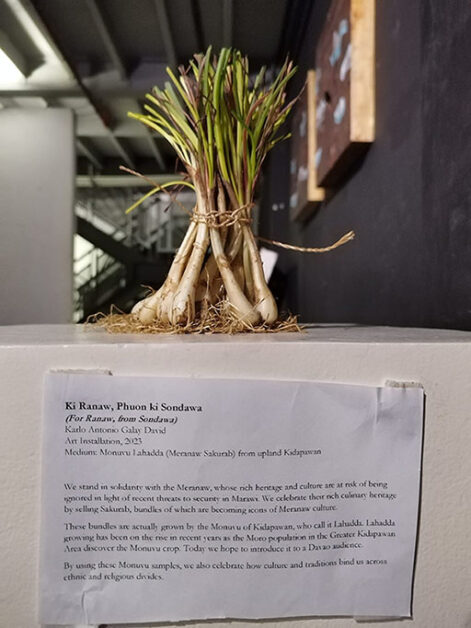

The vegetable I was selling was Monuvu lahadda, an indigenous strain of scallion that had been grown in the Kidapawan uplands since time immemorial. I was selling it as a conceptual art installation, “Ki Ranaw, Phuon ki Sondawa (To Ranaw, from Sondawa),” part of Gallery Down South’s exhibit Conflict of Forms, which will be open to the public in Davao’s Poblacion Market Central until January.

The Lahadda was being sold as sakurab, the Meranaw name for the crop, as a gesture of solidarity with the people of Marawi and the Ranaw in the wake of the recent bombing in the Mindanao State University Main Campus. The bombing, which clearly targeted Christians, had cast the Meranaw in an unfairly negative light, and bigotry has been on the rise in public fora.

By displaying, selling, and offering opportunity to the public to experience sakurab—the key ingredient for that iconic Meranaw condiment, palapa—I hope to help undo the present stigma and remind everyone what a rich, beautiful, and unique culture the Meranaws have.

“Ki Ranaw, Phuon ki Sondawa” was also an opportunity to put the spotlight on Monuvu lahadda growing in Kidapawan. In recent decades, the growing of lahadda among the Kidapawan Monuvu has declined as coloniality has discouraged them from continuing any part of their culture, include cuisine. But in recent years the Moro communities in North Cotabato have discovered the Monuvu supply, and growing has been on an upward trend. Moro cuisine has been literally helping revive Monuvu agriculture.

The positive energy of that inter-ethnic symbiosis is also something I wanted to transmit in the art installation—“Conflict of Forms,” which is the brainchild of Kublai Millan, is intended to be a reflection and statement on the ongoing conflicts in the world, most especially in Gaza and Marawi. The exhibit also features works by Millan, Davao’s Jeff Bangot and Tagum’s Vic Dumaguing, filmmaker Ar Ar Nwebe, and journalist Stella Estremera, who all make their own statements on the need to bridge divides.

In all the exhibited artworks, there has been a dialogue with the material.

This has been especially the case for me. I have worked with lahadda/sakurab for some years now, both as ingredient in cooking and as subject matter for writing. In 2017 I was one of the first to note that lahadda and sakurab are synonyms (recent studies identify it as Allium chinense), and I have been raising awareness about it since, especially in Kidapawan, where the majority of people have never heard what is perhaps the most historically significant indigenous crop of their town.

In 2018, I used it as title and central image of the short story “Lahadda,” which was a roman-a-clef story about the Palera Massacre of 1971 (a family of Meranaws, the Galaw Family, were massacred by paramilitary forces in a remote sitio in Kidapawan, the motivation a combination of landgrabbing and entertainment). The story was published by the Thai Ministry of Culture and the Writers Association of Thailand as the Filipino representative story to its ASEAN Fiction anthology.

Earlier this year, when we opened the last exhibit of the Kidapawan City Cultural Heritage Museum, we used the lahadda as a symbol of inter-ethnic harmony during the opening program.

But even now I am still learning much from it. While setting up the installation I was consulting both Datu Melchor Bayawan (my long term cultural partner with the Kidapawan Monuvu) and Meranaw artist Hassanoden bin Hashim of Marawi. It emerged that both cultures have very different ways of processing the crop. While the Monuvu usually eat the whole plant, the Meranaw more often eat only the bulbs. The Monuvu use it fresh as Loggu (sautéing base), and it is therefore sold thoroughly cleaned. The Meranaw, on the other hand, prefer that the bulbs are slightly dried before being cooked into palapa, and they are often sold in bundles with a bit of the soil still on the bulbs.

Setting the installation up became an opportunity to spend time with the medium: Datu Melchor sent me very fresh bulbs that had been carefully washed and soaked in water, I had to dry them with paper towels and bundled them like they would be in a Meranaw padian (market). They were prone to being slimy when wet, but grew more fragrant as they dried. I was banking on the humidity of the exhibit space and the gallery lights to get them to dry and become even more fragrant in the coming days, but they had been sold out on the opening!

When setting the bundles up I arranged them to form a circle, with a bundle set on a pedestal at one far end. Visitors both saw the mountain Palaw a Magatoring looming over the Ranaw (specially as seen from MSU Marawi), and Sondawa (Mt Apo) looming over Linwo’t Saarong (Lake Venado).

I was not the only one, however, whose artworks were dealing intimately with material.

Kublai, Jeff, and Vic produced compelling paintings that also happened to be historical artefacts. With their signature styles, they painted on squares made out of corrugated roofs that were salvaged from Ground Zero in Marawi. The roofs are dented and riddled in bullet holes from the 2017 siege, and the artists painted around these cavities and contours. Kublai had built a memorial monument for fallen soldiers in the city, and the roofs were part of what he, Vic, and Jeff got in return.

The upcycling of these bits of war rubble into art is both a distinctly contemporary creative approach and a continuation of the ancient Mindanawon tradition of zero-waste celebration of the provenance of material. Kodponguru-an, it is called by the Obo Monuvu, and it is at the heart of their tradition of Pusaka (the keeping of heirlooms). Old things only became Pusaka because instead of being discarded they are valued for their provenance and backstories.

And it is a practice that sees its charm most in architecture. Moro, Monuvu, and Settlers alike practice upcycling in Kidapawan by reusing the remains of old buildings to build new ones. Any of the paintings in Conflict of Forms would not be thematically out of place, for instance, in Kidapawan’s Madriguera Building, which had been constructed using wood from the old Madriguera House (which once stood on its location and which was once home to Kidapawan Mayor Dr. Alberto F. Madriguera).

We learn to celebrate what we have when we discover what others have, the delight at the otherness of what we have never experienced before also a prompt to cherish what is familiar to us—this is what I call Pakig-iniya, a topic Bro. Karl Gaspar has written of in MindaNews when he reviewed my book.

This, I feel is how we make the best of our differences and contrasts, and it is how we can emerge better from our diversity. Kidapawan has so much perspective to offer to the world.

[MindaViews is the opinion section of MindaNews. Karlo Antonio G. David has been writing the history of Kidapawan City for the past thirteen years. He has documented seven previously unrecorded civilian massacres, the lives of many local historical figures, and the details of dozens of forgotten historical incidents in Kidapawan. He was invested by the Obo Monuvu of Kidapawan as “Datu Pontivug,” with the Gaa (traditional epithet) of “Piyak nod Pobpohangon nod Kotuwig don od Ukaa” (Hatchling with a large Cockscomb, Already Gifted at Crowing). The Don Carlos Palanca and Nick Joaquin Literary Awardee has seen print in Mindanao, Cebu, Dumaguete, Manila, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Singapore, and Tokyo. His first collection of short stories, “Proclivities: Stories from Kidapawan,” came out in 2022.]