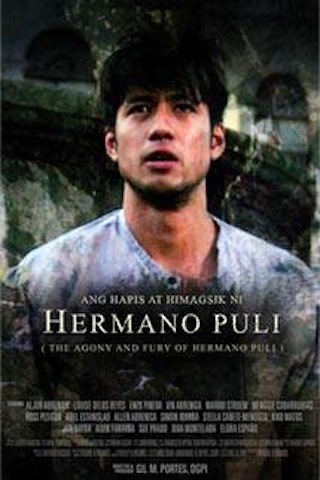

FILM REVIEW: Ang Hapis at Himagsik ni Hermano Puli

Screeplay: Eric Ramos

Director : Gil Portes

Producer: Rex Tiri under T-Rex Entertainment

Title Role: Aljur Abrenica

Karl M. Gaspar CSsR

DAVAO CITY (MindaNews/24 Sept) — In 2007, I searched for the tomb of Apolinario dela Cruz – more popularly known in historical narratives as Hermano Puli – hoping that I would finally have the chance to pay my respects. I searched all over Quezon – the birthplace of the peasant revolts that erupted in the tail-end of the Spanish Regime – to no avail; I was told there was a statue to honor him in his hometown somewhere in Lucban, Quezon (formerly known as Tayabas). But there is no known tomb where his body was buried, where one can light a candle, put flowers and say a prayer of thanks for what he did to contribute to the building of a nation we ultimately would refer to as the Republic of the Philippines.

Why go to all that trouble searching for the tomb of this forgotten hero? I had not known of Hermano Puli in all the years that I underwent my basic education and college course; hardly any textbook made a reference to his life and heroism. Truly, he has been forgotten much like many other folk heroes of the various parts of the country who resisted colonial rule through the Spanish and American epochs. It was only when I did my Philippine Studies course at UP-Diliman and encountered Reynaldo Ileto’s seminal book – Pasyon and Revolution: Popular Movements in the Philippines, 1840-1910 (1979; Ateneo de Manila University Press) that I realized how important the life of Hermano Puli was to the nascent revolutionary movement that led to the founding of the Kataas-taasang Kagalanggalangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan.

Gil Portes’ admirable movie – Ang Hapis at Himagsik ni Hermano Puli – showing nationwide this week including theatres in Davao City – provided me the answer why there is no existing tomb of Hermano Puli. At the end of the film, where subtitles indicated what happened to Puli’s martyrdom and how the struggle he began helped to spark the revolutionary fire that became a widespread movement, the viewer is given this information: his dead body was chopped to pieces and scattered all over. In fact one of the last scenes has his severed head stuck to a pole and displayed publicly with a sign which echoes the words of the hapless victims of the dreaded drug war of our times today.

Gil Portes’ admirable movie – Ang Hapis at Himagsik ni Hermano Puli – showing nationwide this week including theatres in Davao City – provided me the answer why there is no existing tomb of Hermano Puli. At the end of the film, where subtitles indicated what happened to Puli’s martyrdom and how the struggle he began helped to spark the revolutionary fire that became a widespread movement, the viewer is given this information: his dead body was chopped to pieces and scattered all over. In fact one of the last scenes has his severed head stuck to a pole and displayed publicly with a sign which echoes the words of the hapless victims of the dreaded drug war of our times today.

Is it a good film worth patronizing? Should we all troop to the cinema and watch this film? Certainly, if only to know more about this young man and his heroic deeds and to have an inkling how oppressive the Spanish colonial period was to our ordinary people. It captures the main highlights’ of Puli’s life: on 2 November 1841, the 27-year-old Apolinario dela Cruz is arrested and turned over to Lieutenant Colonel Joaquin Juet, the vindictive new governor of Tayabas. During a summary trial the next day, he faces Juet and Padre Manuel Sancho, the parish priest of Lucban who accused him of being a rebel.

In the course of the Inquisition, the viewer knows about the Confradia de San Jose, a religious movement began by Puli as a charismatic young man. Because it was a religious brotherhood (but open to women) that preaches love and equality for all, it steadily attracted the attention and membership of the ordinary folks. It would attract thousands of followers in just four years, culminating in its development into a resistance group taking up arms against the Spanish regime. In 1835, Hermano Puli left for Manila to pursue deeper spiritual enlightenment. Turned down by a number of religious orders where he applied to become a seminarian, he ended up working as an orderly at the San Juan de Dios hospital, which leads to his acceptance as a lay brother of hospital’s own confraternity. Thus the name Hermano added to his nickname Puli. As the Confradia de San Jose flourished and became a force to reckon with, the church officials’ persecution of the Confradia and his members began in earnest.

The film provides the needed visual images to Ileto’s book and helped to make us understand the roots of Katipunan and how the Catholic faith of the early 1800s helped to give rise to a liberation-oriented consciousness of landless peasants. This is liberation theology in the Philippine setting, arising at least a century before this theology got articulated in the Latin American context. For those who need to know the different theories of rebellion, it introduces the student to the phenomenon of millennirianism, where ordinary peasants revolt against their oppressors on the basis of a belief system promising the dawn of a new day when the people will be set free from their yoke.

Unfortunately, a cineaste with a high expectation of this kind of film genre can be disappointed after viewing it. Unlike historical films like Jerrold Tarog’s General Luna, Marilou Diaz’ Jose Rizal and Celso Ad. Castillo’s Asedillo, Portes’ Hermano Puli film is not able to engage the viewer in a manner that at the end of the film, the viewer feels elated and inspired by a mythical truth whose meaning is timeless. It lacks gravitas and it failed to develop a momentum from beginning till the end that can be thrilling for the viewer. It tended to be very predictable with hardly any surprises; making it quite dull from the middle part of the movie.

For those who studied Ileto’s historical narrative seriously, the film fails to explain two very important aspects of what made Ileto’s struggle very historic and unique. While the credits showed that a UP scholar was made a consultant of the film, the finished product hardly touched on two of these integral aspects: first the underlying peasant struggles of the landless peasants that helped explain how the feudal mode of production of the times served as the triggering factor in the landscape that fueled the people’s revolutionary fervor. Yes, there are graphic scenes of how the Spanish forces maltreated the natives, but these were actual incidents of physical torture but not linked to the main reason why the peasants embraced the radical messages of Puli.

Ileto’s thesis – that the constant reading and chanting of the Pasyon provided the symbolic spring from where their courage to resist arose – was not given too much attention. While one hears the chanting as part of the musical score, no attempt was made to link the symbolic language of the Pasyon to how the critical consciousness of the peasants arose and solidified to the point where they were willing to give up their lives for their cause. But this would have been possible only within the historical and land realities of the times in Central Luzon. One therefore has a problem accepting the film’s assertion at the end that of the many revolts during the Spanish times, this was the only one that arose on the basis of the people’s struggle to have religious freedom. This is rather a simplistic conclusion; and the fact is that there were other revolts that did touch on people’s belief system.

Still, we have to praise Portes and the rest of the production team of Hermano Puli for this film project which rarely comes our way, given the average moviegoer’s desire for escapist films rather than those that could help to anchor us within our history and explain how the Republic arose. There are also many aspects of the film worth mentioning including the acting of the cast as an ensemble, the production design and its ability to transcend its budgetary limitations as an indie film.

It is quite tragic that Puli and other heroes have not been given their due – which seems to manifest where we are as an ungrateful nation – but that a film is made about them and so few of us would want to go and see it. (In fact when I viewed it, there were only three of us inside the theatre). Perhaps the DepEd, CHED and other government agencies could find a way so that this film could be shown to the student population of this country.

Meanwhile, we in Mindanao should push for the filming of our own heroes who have long been forgotten including Sultan Kudarat, Mangulayon and so many others.[Redemptorist Brother Karl Gaspar is Academic Dean of the Redemptorists’ St. Alphonsus Theological and Mission Institute (SATMI) in Davao City and a professor of Anthropology at the Ateneo de Davao University. He is author of several books and writes two columns for MindaNews, one in English (A Sojourner’s Views) and the other in Binisaya (Panaw-Lantaw)]