A heavy dose of conspiracy theory, denial of human rights violations during the Marcos dictatorship and casting of democracy icon President Corazon Aquino as villain were among the scores of martial law and EDSA-1 related disinformation debunked by Tsek.ph.

Of the 326 fact checks curated from Nov. 21, 2021 to mid-February 2022, 58 are classified as martial law fact checks because they concerned themes covering the martial law period, the EDSA People Power Revolution and the administrations of President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and Corazon Aquino.

Tsek.ph is a collaborative fact-checking initiative of 34 partners from academe, media and civil society project for the May 9 elections. Tsek.ph builds on its success as a pioneering collaborative project in the 2019 elections and is supported by the University of the Philippines, Google News Initiatives and Rakuten Viber.

The martial law fact checks indicated how disinformation was used to rehabilitate Marcos who held power from 1965 to 1986 when he was ousted by the people-led uprising. The Marcos dictatorship was responsible for human rights violations, extrajudicial killings, press censorship and plunder. It also plunged the country into an economic crisis.

Attempts to erase or burnish the discreditable record of Marcos are seen through various forms of disinformation on social media platforms.

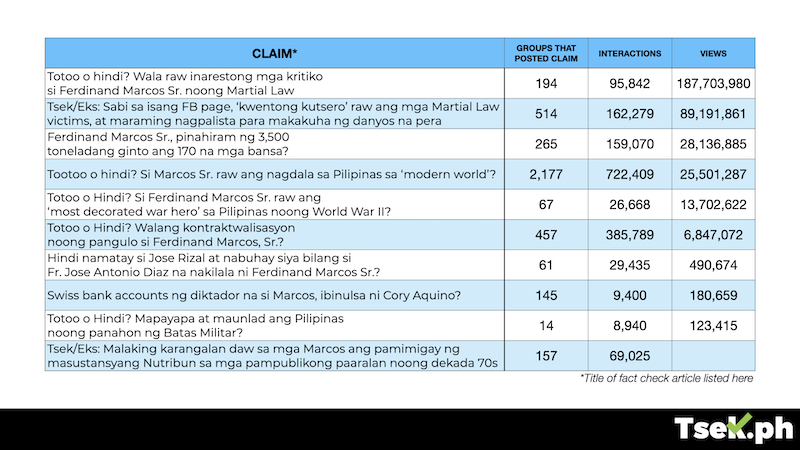

The most viewed claim was that no Marcos critic was arrested during martial law, which earned the rating “False” and collected 95,842 interactions and 187,703,980 views. The figures were culled from Meta’s social media monitoring tool Crowdtangle, which tracks public Facebook pages and groups.

The no-arrest claim was made by Juan Ponce Enrile, Marcos’ former defense secretary, in a September 2018 interview by Marcos’ son and presidential hopeful Ferdinand Marcos Jr. for the latter’s Facebook page. It resurfaced in late September last year and has accumulated 40,081,269 views since.

Other martial law fact checks that went viral include the made-up Maharlika Kingdom and Tallano gold, which are both examples of disinformation as a conspiracy theory or a belief that a secret organization is behind an event or phenomenon.

The myth that Marcos was a war hero, and the most decorated one at that, also refused to die. Marcos supporters also continued to insist that the ill-gotten wealth cases filed against him and his family have all been dismissed even when the Supreme Court, Sandiganbayan and foreign courts have ruled its forfeiture and return to the country because it was unlawfully acquired.

Disinformation agents targeted Aquino because of her decision to mothball the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant, among others. She was also falsely accused of stealing not only the elections from Marcos in 1986 but also pocketing his Swiss bank accounts.

Infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales

Infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales

Electoral misinformation

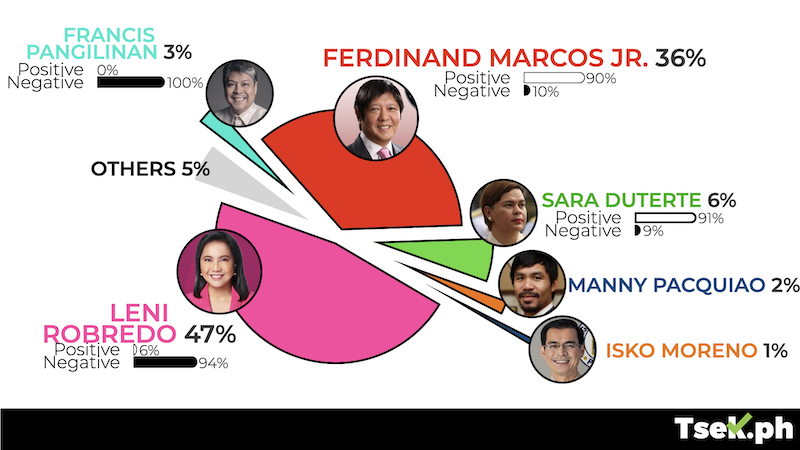

A preliminary analysis of fact checks covering all types of election-related misinformation, including for the martial law period, shows that that misinformation revolved primarily around Marcos Jr. and independent presidential candidate Leni Robredo. Nearly half referred to Robredo and a third to Marcos Jr.

Data show Robredo reeling from preponderantly negative messages and Marcos Jr. enjoying overwhelming positive ones. Of the false or misleading narratives involving Robredo, 94% were aimed against her, while all the narratives that mentioned her running mate, Sen. Francis Pangilinan, were likewise negative.

On the other hand, nine in 10 of narratives about Marcos Jr. and his running mate, Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte, favored them.

Marcos Jr., for example, was falsely depicted as a victim of Robredo’s cheating in the 2016 vice presidential race. This even when the Supreme Court has ruled that he had failed to prove his allegations of poll irregularities and had chosen instead “to make sweeping allegations of wrongdoing.”

Supporters also made it appear that his no-show at the interview with GMA’s Jessica Soho cost the network millions of advertising revenues, a falsehood.

To date, Marcos Jr. has chalked up the most numerous “fake” endorsements of his candidacy. The “endorsers” ranged from a Lebanese-American adult star passed off as a Saudi princess, 11 mayors from Camarines Sur where Robredo hails from and Miss Universe runner-up Venus Raj, a Bicolana like Robredo, to celebrity Kris Aquino, former senator Mar Roxas, President Rodrigo Duterte, and even New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and the giant fast-food chain Jollibee.

False narratives that Robredo was getting set to cheat this May abound. She has been linked to the “hacking” of Comelec servers, which the poll body said never happened, and accused of using her Bayanihan E-Konsulta to collect voter information, meeting with officials from the tech platform Meta, and of vote-buying.

Disinformers have also projected her as intellectually inferior, fabricating or mangling statements she previously made on various issues. False allegations also circulated that she failed to bring aid to victims of disasters, including the Marawi siege and the recent typhoon “Odette.” In contrast, Marcos Jr. was shown in various relief operations, one of which turned out to be the foundation anniversary celebration of a barangay and the other at a Christmas gift-giving event.

The rash of disinformation in the form of positive messaging for the Marcos-Duterte tandem and negative ones for Robredo-Pangilinan tandem is reminiscent of the 2016 campaign playbook the Duterte camp successfully used on his opponents. This playbook was adopted by supporters of the Sara Duterte-led Hugpong ng Pagbabago for administration candidates in the 2019 midterm elections. This strategy involves viral outbreaks of false information from the specific actors and narrative cache of fringe sources.

Infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales

Infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales

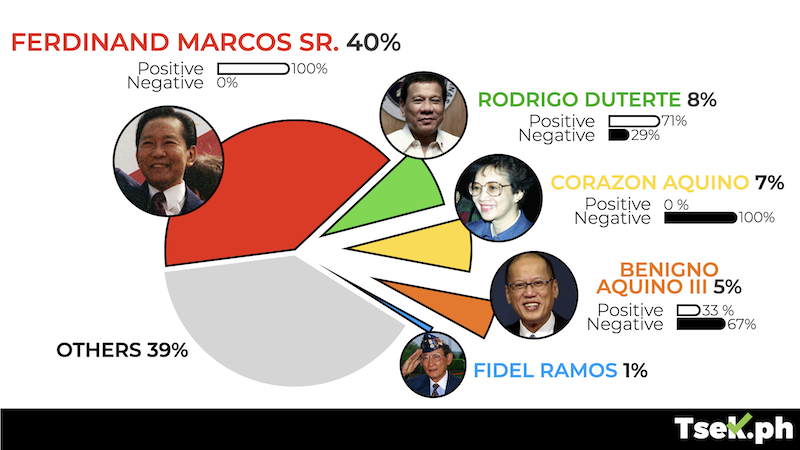

Marcos Sr. and Aquino, as well as former presidents Fidel Ramos and Benigno Aquino III and incumbent president Duterte, were among the 29 non-candidates who were the subjects of misinformation.

Consistent with the inaccurate narratives about their children, those flagged by fact-checkers all extolled the late Marcos while 71% of the reports about Duterte were more positive than negative. These were mostly exaggerations or unfounded claims about their achievements, designed to project the Marcos-Duterte team as in a position to supposedly continue these legacies of their fathers.

The opposite is true for Corazon Aquino where all the falsehoods sought to discredit her and her administration, and by extension, her son Aquino III.

Infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales

Infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales

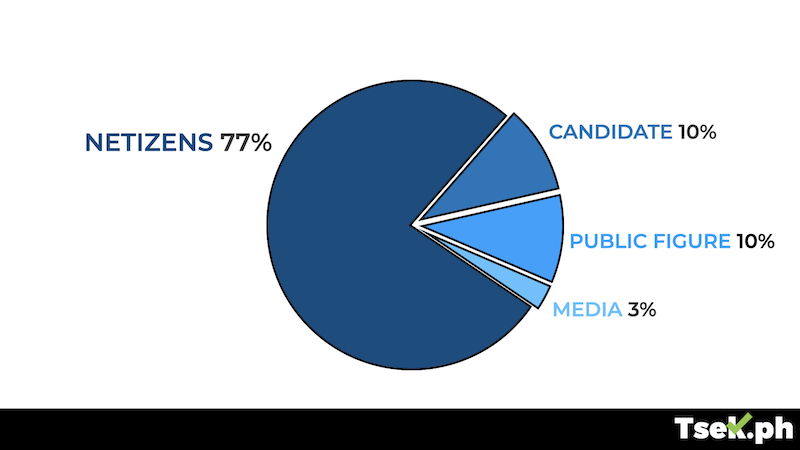

The fact checks showed that netizens, mostly social media users, circulated slightly more than three-fourths of the factual inaccuracies that were flagged. Candidates and public figures each accounted for a tenth.

Infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales

Infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales

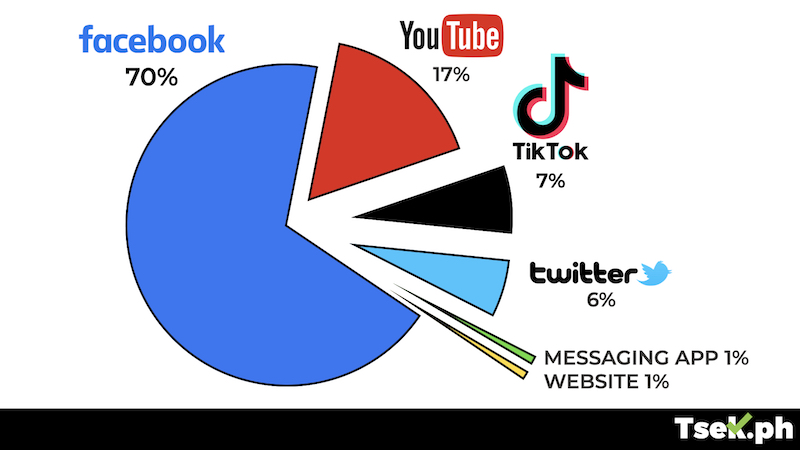

Facebook and YouTube are the platforms through which the false and misleading claims were chiefly distributed. Seven in 10 claims that were debunked appeared on Facebook pages and groups, followed by YouTube (17%). Fact checkers also spotted spurious claims on TikTok (7%), a point ahead of Twitter (6%). About a third of the fact-checked claims appeared in two platforms.

Infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales

Infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales

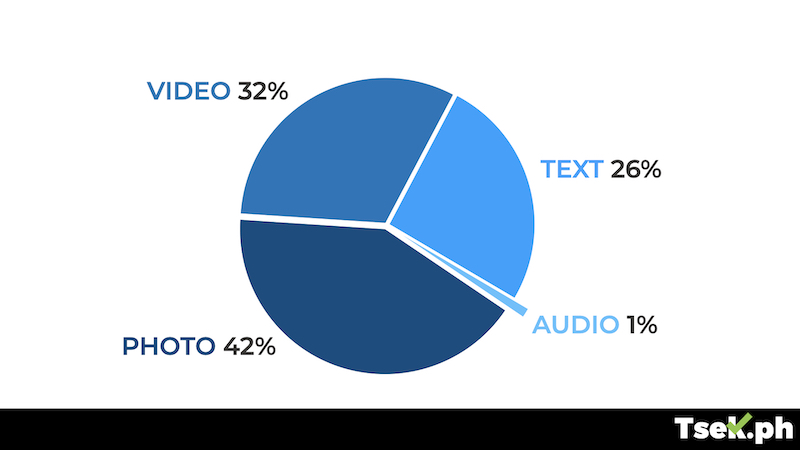

Netizens also resorted mainly to visual content to spread false or misleading narratives. Photos, including those with overlaid text and quote cards, were the most used by misinformation spreaders (42%), followed by video (32%) and text (26%). Altered quotes and captions, doctored photos and spliced videos were common.

Infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales

Infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales

Distribution of certain claims also appeared coordinated. Of an initial 95 claims where Crowdtangle data were available, 51 claims or 54% were posted in at least of 50 Facebook pages or groups, many of them on the same day. The median was 87 public Facebook pages or accounts.

About 45% of the claims had picked up total interactions (likes, shares and comments) exceeding 10,000.

In all, the spurious and suspicious claims that Tsek.ph partners have flagged were posted in 1,325 Facebook pages and groups, with at least 200 of them bearing the names of Marcos and Duterte or their variations. (Text by Ma. Diosa Labiste and Yvonne T. Chua; infographics by Felipe Jose Gonzales)