DAVAO CITY (MindaNews /01 July) — Mercy Muhamad, 44, dismounts from the rusty bicycle’s sidecar even before her husband has come to a full stop. This the fourth dumpsite for them, with three more to go before calling it a day.

She is already rummaging through the heap of rubbish when her husband Abdul Muhamad (“13 years older than me,” she laughs) joins in. The couple works with surgical precision, instinctively knowing which plastic bag contains salvageable material to be sold at the junk shop.

For the past seven years, this has been their livelihood. But today– just like in the past three months — both are wearing a cloth mask.

Although cloth masks, designed using cut fabric, are not as effective compared to medical masks, they have the added advantage of being reused multiple times. The Department of Health has recommended that they should be washed with warm water and soap every day.

Since they are reusable, they do not end up in waste bins, unlike surgical masks.

In the past few weeks, Mercy has picked the habit of holding a stick, its brown membrane blackened by grime and grease, instead of her bare hands.

“I carry this around with me just in case,” she says, as she holds up the stick at the garbage collection point along Padre Gomez St. Not long after, she uses it to poke a soiled medical mask out of the way.

“I see them regularly nowadays,” she adds. “On average, I can find 15 to 20 of them every day.”

Mercy Muhamad has returned to scavenging in the dumpsites of Davao City for salvageable materials that could be sold to junk shops. MindaNews photo by JOEL ESCOVILLA

Mercy Muhamad has returned to scavenging in the dumpsites of Davao City for salvageable materials that could be sold to junk shops. MindaNews photo by JOEL ESCOVILLA

To demonstrate, she stands from her crouched stance then proceeds to count nine discarded medical masks. And those are only what she spots from her position. There are still plenty of them stuffed inside plastic bags and cardboard boxes.

The couple hails from Cotabato City and when her husband lost his job seven years ago, they hopped on a bus for the six-hour ride to Davao City for better opportunities. With the help of relatives, they rented a small space in the slums near the Sta. Ana wharf and have lived there since.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted their livelihood like no other. She says they earned 400 to 500 pesos (10 USD) before the lockdown, but now they consider it a good day if they can bring home 300 pesos (6 USD).

When Mayor Sara Duterte announced a lockdown in mid-March, the couple and their two children — aged 6 and 18 — had to stay home, fully dependent on the food aid from the city government as the economy crawled to a standstill.

But they can’t stay holed out forever as expenses are piling up and school enrollment is approaching fast. When the city shifted from Enhanced Community Quarantine to General Community Quarantine on May 16, the couple went back to work.

“I didn’t want to go out because it is scary,” she says. “When I see a (medical) mask, I become paranoid. What if I get infected by the virus?”

No worries?

Dr. Lenny Joy Rivera, assistant regional director of the Department of Health in Davao Region, allayed fears that face masks pose health hazards since ordinary people do not have sustained contact with COVID-19 positive patients.

Frontline healthcare workers, on the other hand, must be equipped with complete personal protective equipment (PPE) to minimize the risk of getting infected with the virus since they have sustained exposure and close contact with patients, infected liquid, plasma, and other materials.

A common sight these days: used surgical masks thrown into the bin of households in Davao City. and brought to garbage collection points. Discarded PPEs (Personal Protective Equipment) in hospitals are collected by a private contractor that uses pyroclave. MindaNews photo by JOEL ESCOVILLA

A common sight these days: used surgical masks thrown into the bin of households in Davao City. and brought to garbage collection points. Discarded PPEs (Personal Protective Equipment) in hospitals are collected by a private contractor that uses pyroclave. MindaNews photo by JOEL ESCOVILLA

But Rivera agreed that households need to learn how to properly manage used medical masks, face shields, and gloves. For instance, separating them into a designated container, disinfecting it before dumping it on site would drastically minimize health risks.

“We will discuss that with the city, as well as the provinces, to release some guidelines for them to be aware of what to do and also avoid a community scare,” she says. “Because they might be unnecessarily alarmed when they see a mask somewhere.”

Davao City tops Mindanao in terms of COVID-19 cases. As of 5 p.m. on June 29, the Davao Center for Health Development recorded 411 cases with 301 recoveries and 28 deaths in Davao City out of the Davao region’s 529 cases, 356 recoveries and 32 deaths.

At least eight barangays in the city have been categorized as “very high-risk” and five others as “high risk” areas and people have been warned against going to these areas from June 27 to July 5 due to the high incidence of localized transmission.

Designated COVID-19 facility

The state-owned Southern Philippines Medical Center (SPMC) has been identified as the lone designated COVID-19 treatment facility in Davao. As of June 29, it had accepted 426 positives, 306 of whom recovered – with median age of 37 — while 33 died, with median age of 52.

The SMPC is a participant in the global solidarity trial to determine the efficacy of potential drugs to combat SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

The Southern Philippines Medical Center (SPMC) in Davao City. MindaNews photo by MANMAN DEJETO

The Southern Philippines Medical Center (SPMC) in Davao City. MindaNews photo by MANMAN DEJETO

On the average, according to Dr. Leopoldo Vega, SPMC chief until his designation early this month as Health Undersecretary, each healthcare frontliner is given 25 sets of PPE as they attend to the patients. For patients classified as moderate, the assigned health worker is given 10 to 15 PPEs. For those treating patients with mild symptoms, they are provided five PPEs each.

The hospital management is asking donations while also ramping up its procurement process to meet the demand.

But how does SPMC dispose of the PPE waste to prevent cross-contamination?

Dr. Ricardo B. Audan, Chief of Professional Services at SPMC and concurrent OIC SPMC chief, said the facility is equipped with an autoclave and incinerator but these are not being used for COVID-19 wastes. Instead, they outsource it to a third-party company to dispose of the soiled PPEs.

“Before we give the soiled PPE, we have a protocol on that. We put it in a plastic bag, disinfect and seal it before we place it in our garbage bin,” he reveals. “There is a designated place where the outsource company picks up that soiled PPE.”

Pyroclave

RAD Green Solutions is the contractor that collects all discarded PPEs from hospitals and COVID-19 centers in the city. Twice a week – on Wednesdays and Saturdays – its insulated vans go around to collect the accumulated waste and bring it to its pyroclave in Obrero.

According to its website, the pyroclave is an ISO 9001 facility designed to destroy medical waste, without pollutants, unlike the traditional incinerators. The process is also water-free, preventing the waste outcome from leaching downward to groundwater.

James Banados, the operations manager for Mindanao, said that during the pandemic, they have been collecting two tons of waste from the SPMC alone during the bi-weekly retrieval and another ton from the city’s COVID-19 centers. He said SPMC is a new client of the company. The city’s other hospitals are also their clients.

According to Mayor Duterte, Davao City has prepared quarantine facilities for confirmed patients with mild or moderate symptoms who do not need emergency medical intervention. They also have isolation centers used by suspected cases awaiting confirmatory results from the swabbing samples.

“If we count everything, we have 544 beds and 11 facilities,” she reveals.

RAD collects waste from the facilities currently used.

All collected wastes are sanitized and disinfected before they are loaded to the insulated van. The collectors all wear full PPE covering, similar to Hazmat suits.

The collectors are also regularly monitored using the rapid test kits and body temperature scanners, Banados said.

RAD Green Solutions uses pyroclave, an ISO 9001 facility designed to destroy medical waste, without pollutants, unlike the traditional incinerators. (From the website of RAD Green Solutions)

RAD Green Solutions uses pyroclave, an ISO 9001 facility designed to destroy medical waste, without pollutants, unlike the traditional incinerators. (From the website of RAD Green Solutions)

Before the wastes are stuffed into the pyroclave, they are first treated with glutaraldehyde, a highly toxic disinfectant used to sanitize heat-sensitive equipment.

The pyroclave is a proprietary technology that utilizes a process called pyrolysis. The company uses water as the catalyst to produce more heat using less fuel (LPG). The higher water temperature enables total destruction of infectious and solid waste without the toxic by-products.

For now, Banados said, they are still nowhere near the capacity of their machine but if in the event that PPE waste volume multiplies, they can always ramp up their operation through multiple personnel shifts.

He said this would be easy since each treatment cycle for medical waste is finished in 30 minutes.

“As part of our contract with hospitals and the city government, we are not allowed to dump medical waste at the landfill,” he said.

The city’s sanitary landfill is located in Barangay New Carmen, about 20 kilometers from the city’s central business district.

Shredded, treated waste

Banados said they have a storage cell near the sanitary landfill in Barangay New Carmen where all the shredded and treated medical wastes are deposited. Although RA 6969 classifies treated hazardous waste as municipal waste, the Davao City government directed RAD in 2016 to establish a dedicated facility for its own treated wastes so they do not end up at the landfill.

The company is preparing a site in San Isidro, Bunawan District, about 24 kilometers north of Davao City Hall, to convert into a private landfill. He said they are already complying with the requirements for the environmental compliance certificate from the Environmental Management Bureau of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

“Our storage cell is near capacity but if our sanitary landfill is not yet completed by then, we have a contractor also in Manila who can take our waste outcome,” he said.

All roads lead to the landfill

The City Environment and Natural Resources Office (CENRO), which is tasked to collect garbage from the city’s 182 barangays and manage the sanitary landfill, admits that the discarded PPEs from households are becoming a concern.

Lakandiwa Orcullo, Engineer 1 at CENRO’s Environmental Waste Division, explains that household special wastes, which includes discarded face masks and face shields, are outside their purview as directed by Republic Act 6969 or the “Toxic Substances and Hazardous and Nuclear Wastes Control Act of 1990.”

Truck enters the Davao City Sanitary Landfill in Barangay New Carmen . MIndaNews photo by GREGORIO C. BUENO

Truck enters the Davao City Sanitary Landfill in Barangay New Carmen . MIndaNews photo by GREGORIO C. BUENO

While the law assigns to the city and municipality the responsibility of collecting special waste, there is a condition for this to take place, as affirmed by Davao City Ordinance 0361-10, or the “Mandatory Segregation of the Solid Waste.”

The ordinance mandates that special wastes should be properly segregated at source. Failure to do so warrants a fine of a minimum of 300 pesos (6 USD) to a maximum of 5,000 pesos (100 USD) or six months imprisonment.

He asserts that it is impossible for the garbage collectors to sort the PPEs from regular wastes at the garbage collection points.

Ultimately, the trucks empty all their contents at the city’s sanitary landfill.

650 to 900 tons a day

According to the Waste Analysis and Characterization Study (WACS), Davao City generates from 650 to 900 tons of garbage daily, with each person estimated to contribute 500 grams of garbage each day. But half of the total volume is considered biodegradable, which could have been composted as fertilizer at home. Meanwhile, 18% is recyclable and only two percent is classified as special waste.

About 80% of the wastes come from households while 20% are from commercial establishments.

“After the lockdown, we are down to 614 tons per day because of the number of establishments that closed down. But we have not conducted a WACS yet (during COVID) to determine if the volume of special waste has increased,” he says.

In fact, during the heightened lockdown under the enhanced community quarantine from April 4 to May 15, the number of garbage trucks moving around the city declined from an average of 110 units per day to 90.

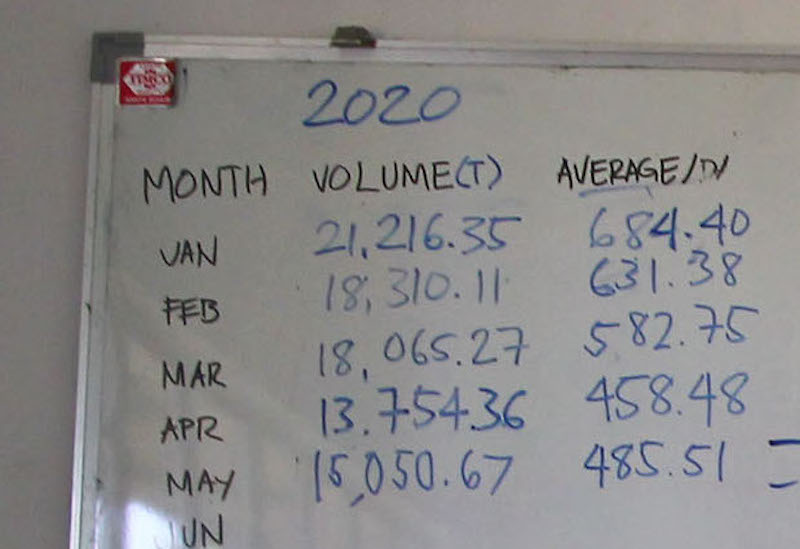

Davao City’s garbage collection per month and per day from January to May 2020. MINDANEWS

Davao City’s garbage collection per month and per day from January to May 2020. MINDANEWS

According to Engr. Daven de Dios, assistant officer in charge of the Davao City Sanitary Landfill, there was a steady decline in the volume of garbage collected by the city during the lockdown.

From a high of 684.40 tons per day in January this year, it was down to 582.75 in March (the lockdown started March 15), 458.48 tons in April when the city was placed under Enhanced Community Quarantine, then slightly increased to 485.51 tons in May. The city shifted to General Community Quarantine effective May 16.

Special waste

Orcullo says that the sanitary landfill, spanning eight-hectares, has a designated spot for special waste to make sure they do not leach to rivers and waterways. But nobody anticipated the widespread hysteria caused by the pandemic, which triggered a surge in the sale of commercial face masks.

The problem of discarded PPEs from households that may end up at dumpsites is a problem that the city naturally inherited. And with no vaccine in sight, Orcullo says they are trying to work a solution under the ‘new normal’ scenario.

“We have already started coordinating with the barangay officials to download information on the need to segregate at source,” he said. “The residents are urged to separate these masks in yellow cellophane for easier identification by our garbage collectors.”

The World Health Organization has a guideline on color-coding medical waste containers. Black is for non-hazardous waste while the color yellow signifies that the contents are infectious waste or pathological waste. According to the WHO recommendation, the container could either be a rigid box or a plastic bag.

Davao City Sanitary Landfill in Barangay New Carmen, Davao CIty. MindaNews photo by GREGORIO C. BUENO

Davao City Sanitary Landfill in Barangay New Carmen, Davao CIty. MindaNews photo by GREGORIO C. BUENO

Davao City discourages people from using non-biodegradable plastics. In February 2020, it approved on third reading the ordinance banning single-use plastics or SUPs. Unfortunately, the implementation of the proposed measure was overtaken by the pandemic. Nevertheless, shopping malls, food, and retail establishments are already using biodegradable plastic bags, ecobags or brown paper bags to avoid getting slapped with a fine.

Meanwhile, Orcullo said the city is also scouring for new areas to establish another landfill, as the existing one, opened in 2010, is nearing its 10-year lifecycle.

“Abnormal time”

Lawyer Mark Peñalver, policy advocacy specialist of the Davao-based environmental group, Interface Development Interventions, Inc., says the health department and city government must adopt innovative measures for the proper disposal of PPEs to avoid the possible transmission of the virus.

“We are in an abnormal time wherein face masks, gloves, and other personal protective equipment (PPE) are not only limited to hospital use but have become an integral part of our everyday lives due to the current health crisis,” he says.

But Peñalver admits that as an environmental group, they have their work cut out for them, as well.

“We see that the years of IEC (information, education and communication) campaign that we’ve been conducting with regard to waste management is still not enough because people are still not aware or still not compliant with our existing policies,” he explains. “This is evident by the increased disposal or generation of healthcare wastes.”

But he sees some opportunities, as well. For example, the group is looking to recalibrate their messaging to optimize the efficacy.

“This is also a good opportunity to engage the local government unit to review existing policies on waste management, especially in addressing PPE, and come up with a more comprehensive plan,” Peñalver says.

He adds, “As what we normally do in policy lobbying, we engage the local government unit through advocating for policies and policy amendments. In this case, we take the initiative.”

Finally, Peñalver says that Dabawenyos should also do their part to avoid putting an undue burden on the environment and healthcare sector. One simple act is to segregate the special waste in a yellow-colored garbage bag for easier identification, then disinfecting it before depositing the trash at the collection points.

“As responsible Dabawenyos, we are also called and mandated to do our part in observing proper waste disposal, especially with our household healthcare wastes, to avoid any health and environmental hazards,” he says.

* * *

Dusk has almost settled and the couple prepares to leave as another scavenger turns up to comb through the stockpile.

When told that the health department does not consider medical masks found at garbage collection points a hazard, Mercy chuckles nervously. “I don’t know. Maybe they are right but I think I will hold on to the stick. I have a 6-year-old who depends on me, so I can’t risk it,” she explains.

Even before Abdul Muhamad could make a full stop at the garbage collection point along Padre Gomez St. in Davao City, his wife Mercy has dismounted to scour for waste that could be sold at the junk shop. This is the fourth dumpsite they visited. From there, they would go to three more dumpsites before calling it a day. MindaNews photo by JOEL ESCOVILLA

Even before Abdul Muhamad could make a full stop at the garbage collection point along Padre Gomez St. in Davao City, his wife Mercy has dismounted to scour for waste that could be sold at the junk shop. This is the fourth dumpsite they visited. From there, they would go to three more dumpsites before calling it a day. MindaNews photo by JOEL ESCOVILLA

Mercy’s husband calls her and she settles on the sidecar. Muhamad slowly pedals away as the rusty bike groans from the added weight.

With a friendly wave, the cloth face covering masked Mercy’s smile but the creases in her eyes gave it away. Two more hours and three dumpsites to go before they return to the safety of their shanty where the cold leftover meal is waiting.

(Joel Escovilla for MindaNews. Escovilla is Associate Editor of Mindanao Times in Davao City. The production of this special report was made possible with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network)