By Karol Anne M. Ilagan and Malou Mangahas

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

THE MAY 2019 elections have been declared to be fraud-free by both election officials and watchdogs, but by all indications, its conduct and process were not entirely fault-free.

Thus far, a few flaws have been exposed: Record numbers of 3,414 voter-counting machines (VCMs) that malfunctioned, 4,067 defective secure digital (SD) memory cards, and marking pens that bled on ballot paper, with nearly all of the pens replaced at the last minute.

These mishaps were not without consequences as election monitoring groups reported late opening of polls, long queues, and delays across the country. Among other things, such inconveniences may have dissuaded voters from waiting their turn to vote.

But from sources within and outside the Commission on Elections (Comelec), PCIJ has learned of a few more, and probably graver, flaws:

- A series of avoidable delays in the procurement of goods and services that led to a revision of the election calendar four times;

- More and bigger numbers of defective machines and supplies than had been acknowledged by the poll body;

- Gross inefficiency and even wasteful spending on the part of Comelec and its contractors; and

- A new ballot layout that apparently led to gross undervoting in the party-list elections.

The VCMs, SD cards, and marking pens are smaller matters, it seems.

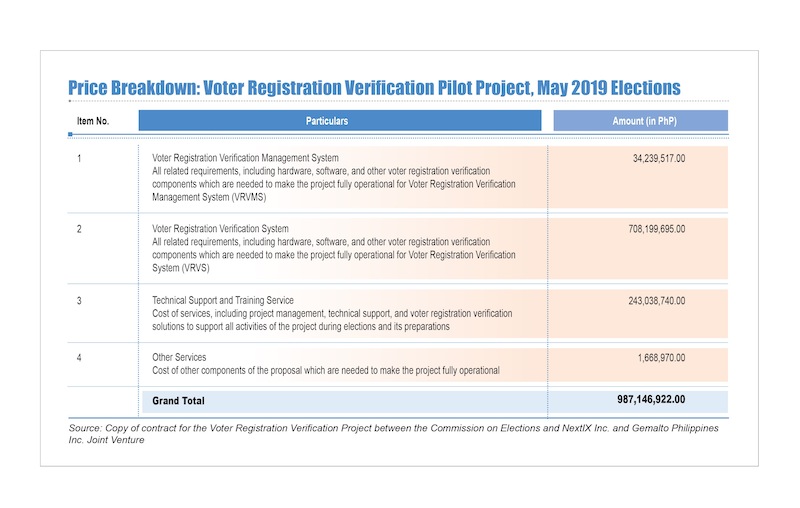

One of the bigger issues involves the Voter Registration Verification Machines or VRVMs, Comelec’s second most expensive contract in the last elections that is worth nearly a billion pesos. (Only the PhP1.178- billion “Election Results Secure Transmission Solutions, Management and Related Services including Data Center Requirements (ERSTSMRS)” contract won by Smartmatic TIM Corporation bests it.)

Whispered issue

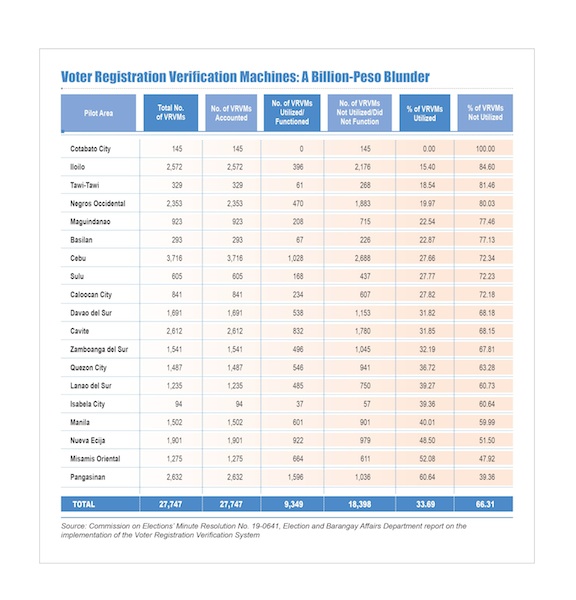

It is a controversy that has not been fully discussed in public and is currently confined in whispers among Comelec and poll watchdog circles. But the fact is that two in three of the  27,747 VRVMs that Comelec had leased for pilot-testing in as many precincts did not work at all. The contract price or taxpayers’ money potentially wasted on this deal: PhP987,146,922 or some 18 percent of the poll body’s total expenditure for the May 2019 elections.

27,747 VRVMs that Comelec had leased for pilot-testing in as many precincts did not work at all. The contract price or taxpayers’ money potentially wasted on this deal: PhP987,146,922 or some 18 percent of the poll body’s total expenditure for the May 2019 elections.

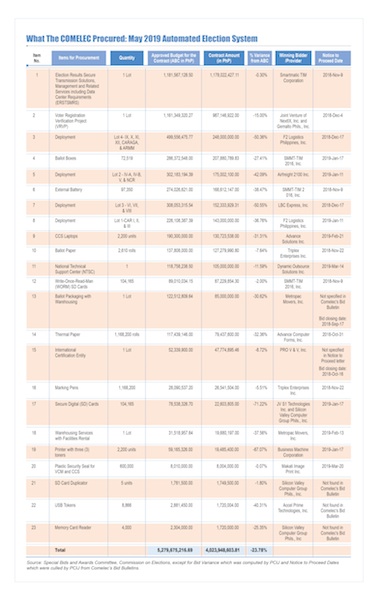

In all, Comelec procured some PhP4.024 billion for 23 different contracts for goods and services for the elections last May. It had allotted, however, a bigger authorized budget for the contract (ABC) of PhP5.279 billion for all the 23 contracts. In all instances, the 23 contracts were awarded way below the total ABCs, resulting in a PhP1.256-billion excess, or a combined price variance of negative 23.78 percent.

For 16 of the 23 contracts at least, the awarded amounts were from 10 percent to 70 percent lower that the ABCs, pointing to an apparent failure of Comelec to assess and peg its ABCs for the goods and services it needed according to sound market standards and project studies.

Dodged rules

Four of the most problematic contracts worth a total of PhP1.32 billion were awarded by Comelec in circumstances that seem to have skirted government’s procurement rules.

For one, the bundled contracts for the ballot paper (PhP127.28 million) and marking pens (PhP26.54 million) were awarded in a negotiated procurement process to the sole participating contractor that had been disqualified in the first of two prior failed biddings for the same contract.

The contractor, Triplex Enterprises Inc., lists Pedro O. Tan as president and other persons surnamed Tan as officers and shareholders. From 2007 to 2019, it secured a total of PhP1.38 billion in contracts from the government procurement service, National Printing Office, and other state agencies.

For another, the PhP22.5-million contract for the SD cards was awarded to a supposed joint venture or JV between two companies: S1 Technologies Inc. and Silicon Valley Computer Group Phils., Inc., which, except for three persons, have the same seven directors and officers.

The JV partners, which hold offices at residential addresses in Quezon City, have as common shareholders Joel L. Pe, Mei Nga Ko, Aileen Co, Tiffany K. Tia, Nelson K. Co, Reyna S. Isla, and Milagros R. Fernandez. Toni Teefane Chunpeng appears as another director in S1 Technologies, while Jeanette C. Co and Christine Tan are additional names in the Silicon Valley Computer Group.

From 2015 to 2019, Silicon Valley won contracts worth a total of PhP73,961,164.72 from various government agencies. Its top clients have been the Davao City Government and the Philippine Statistics Authority of Region 12 or SOCCSKARGEN, from which it had won contracts worth PhP14.4 million and PhP4.5 million, respectively, during the period.

S1 Technologies, for its part, had secured PhP360.5 million in contracts from 2007 to 2019 from various state agencies, led by the Department of Health.

Prickliest deal

Of the four most problematic contracts entered into by Comelec for the May 2019 elections, though, the prickliest one is its lease contract for the pilot-testing of the VRVMs, for which it had a marked-up budget of PhP1.16 billion (from the original PhP727 million allotted in 2016).

The VRVMs were supposed to be part of Comelec’s efforts to thwart “flying voters” or those who try to vote either in more than one precinct or by using the name of another voter. With the use of live fingerprint-scanning technology, the VRVMs are designed to verify a voter’s identity and determine whether he or she is registered in a certain precinct.

The VRVMs were supposed to be part of Comelec’s efforts to thwart “flying voters” or those who try to vote either in more than one precinct or by using the name of another voter. With the use of live fingerprint-scanning technology, the VRVMs are designed to verify a voter’s identity and determine whether he or she is registered in a certain precinct.

For the 2019 polls, pilot-testing of the VRVMs was approved for 32,067 precincts, from an original plan of only 23,000 precincts in 2016. The machines were deployed in 14 areas: City of Manila, Quezon City, Caloocan City, Davao City, the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), and the provinces, including all cities, of Pangasinan, Cavite, Nueva Ecija, Cebu, Iloilo, Negros Occidental, Zamboanga del Sur, Davao del Sur, and Misamis Oriental.

But since majority of the leased units were not used at all either because the election officials could not operate them or because they malfunctioned, Comelec would not have sufficient basis that could help inform the full implementation of the project in the 2022 elections. The machines may still be used for voter-registration purposes – that is, if Comelec opts to purchase the problematic machines on or before August 31.

Problematic machines

Comelec Executive Director Jose M. Tolentino Jr. in early June told lawmakers at the Joint Congressional Oversight Committee (JCOC) hearing on the Automated Election System that only 33 percent of the units leased “worked properly without problem” while 66 percent were not used because election officers encountered procedural problems. He also said that an estimated 3,900 units had “inherent defects.”

Comelec’s Minute Resolution No. 19-0641 bears out Tolentino’s statements. According to a copy of the resolution obtained by PCIJ last July 24, 66 percent or two in three VRVMs deployed had indeed either malfunctioned or were not used at all.

The resolution also indicated that in 17 of the 19 pilot areas, the VRVMs malfunctioned or were not used at all; the non-use rate ranged from 51.50 percent to 100 percent.

The resolution, which enrolled the report of Comelec’s Election and Barangay Affairs Department (EBAD) on the implementation of the Voter Registration Verification System (VRVS), also said Cotabato City, Iloilo, and Tawi-Tawi had “the highest percentage of non-functionality/non-use.”

All of the 145 units deployed in Cotabato City were not used. Over eight in 10 of the VRVMs deployed in Iloilo (2,176 of 2,572 machines) and in Tawi-Tawi, (268 out of 329 machines) were unused as well, according to the resolution.

Of the top five provinces with the biggest deployment of VRVMs, only Pangasinan had a use rate of more than 50 percent. The rest, Cebu, Cavite, Iloilo, and Negros Occidental, had low utilization rates ranging from 15 percent to 31 percent.

Comelec’s EBAD said that the “highest percentage of VRVM functionality/use” were reported in Pangasinan (60.64 percent), Misamis Oriental (52.08 percent), and Nueva Ecija (48.50 percent).

These data notwithstanding, Comelec Spokesperson James Jimenez in an interview a fortnight ago said he was not aware of any VRVMs malfunctioning even as he acknowledged that in many places, the machines were not even used.

He said that various reasons prompted the non-use of the VRVMs in many areas: the machines were packed up early because teachers had encountered difficulties; local authorities in BARMM opted to use only the Election Day Computerized Voter’s List; and some Board Election Inspectors (BEIs) and poll clerks got confused with the instructions they got and decided not to use the machines anymore.

According to Jimenez, the confusion had to do with the procedures for machine startup that must be done in a particular order. Comelec conducted training on use of the machine but, he added, those who manned the polls apparently did not remember the lessons quite well.

In truth, there is more to this story than the failing memory or confusion with instructions on the part of election officers.

‘Technical blunder’

On May 8, 2019, with just five days to go before poll day, Comelec En Banc decided to change the general instructions on use of the VRVMs because of an apparent supplier oversight. The general instructions that Comelec first issued in April had served as the reference for the training that election officers underwent on how to use the VRVMs.

Commissioner Marlon S. Casquejo would later express his dissent over the last-minute change that meant the enrolment and validation of the BEIs were no longer required. In his dissenting opinion dated May 14, 2019, Casquejo wrote that the service provider used a different version of the system during the training and that everything had worked then. But after the supplier upgraded the system, an error was encountered every time the BEIs’credentials were being registered.

“We are speaking of millions of pesos for the training alone; lease of venue and food provisions not yet included,” Casquejo noted. “With these last-minute changes, the training, materials, and manuals would be rendered nugatory — all because we want to adjust to the mistake of the service provider.”

The Commission, he said, is “not supposed to compromise its own resolution in order to accommodate the failure or lack of foresight of the service provider to deliver the output it promised.”

“What is involved here is not a mere clerical error,” he added. “A technical blunder occurred by reason of the service provider’s fault which resulted in the impossibility of the service provider to deliver the service it promised. If the latter cannot comply, the solution is to terminate the contract at the expense of the service provider, not accommodate it.”

Multiple issues

Casquejo’s dissent over the last-minute revision of the general instructions went unheeded.

But the issue would later be among the main problems with the VRV system that election officers cited in EBAD’s report. The other problems they listed were “log-in issues (credentials) in connection with EB’s input”; machines that hang, freeze, or shut down automatically; fingerprint scan and manual search functions that lagged; some voters not successfully detected through fingerprint scan; malfunctions triggered by smartcards and passwords issued to election officers; and problems with the printer function of the machines.

Election officers also rued the lack of technical support from the VRVM field technicians. The Unified Reporting System that was supposed to be provided by the National Technical Support Centercontractor was not used in the VRV system technical support room. Calls to the VRV system technical support were thus recorded or noted down manually. Overall reports and statistics could not be generated by Gemalto/NextIX either.

Faced with these problems, many BEIs decided to discontinue using the VRVM and resorted to using EDCVL, the report noted.

The belated decision of the VRVM supplier to use a different version of the system than the one used for the training of election officers has prompted Comelec to hold further payments on the supply contract worth about a billion pesos.

The belated decision of the VRVM supplier to use a different version of the system than the one used for the training of election officers has prompted Comelec to hold further payments on the supply contract worth about a billion pesos.

At a public hearing conducted by lawmakers, Comelec Executive Director Tolentino said that Comelec has issued a resolution directing its Finance Department to freeze pending payments to the VRVM suppliers, Gemalto Philippines Inc. and NextIX Inc., until the Commission completes its investigation on the project fiasco. So far, though, Comelec has already paid the joint venture between Gemalto and NextIX 17 percent of its contracted PhP987 million, or PhP167.8 million.

Though he signed the resolution to increase the ABC for VRV project, Commissioner Luie Tito F. Guia had expressed some reservations on the venture early on. In Minute Resolution 18-0546 promulgated Aug. 24, 2018, Guia noted that the pilot test had no clear implementation plan such as standards, measures, and criteria, as well as a clear basis for deciding whether the project may be implemented in a larger territory or even nationwide.

“There is a need for the Commission to be thorough in conceptualizing, adopting, and implementing IT projects that require large public investment,” Guia wrote, adding that Comelec should also make sure that endorsement by pertinent agencies like the Department of Information and Communication Technology (DICT) or even the National Economic (and) Development Authority (NEDA) is made a requirement for expensive projects such as the VRVP.

Too large for pilot

Guia also pointed out that the target number of units seemed too large for a mere pilot implementation. The 32,000 units, he said, already make up a third of what a full implementation would require. He noted that the project’s ABC also breached the billion-peso mark at PhP1.164 billion.

“A pilot test can result to a decision, either to adopt what is being tested or reject it,” Guia wrote. “If the decision is to reject it, over a billion pesos for a pilot test is definitely high.”

The commissioner suggested that it might make better sense to limit the project to areas where substituted voting is known to be prevalent or in areas that are vulnerable to said practice.

Jimenez has since told PCIJ that Comelec wanted to get a large enough sample so that the poll body could get all of the possible combinations of circumstances. In 2008, he said, the pilot test of the automated election was done in the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao, which had a huge population as well.

“The reasoning was if you can do it in such a difficult place then you can do it in the entire country, no problem,” Jimenez said. “I think the same sort of thinking informed this decision – if you can do it in a large-enough pilot, then doing it in a national scale should be a walk in the park.”

Some election officials think otherwise. The system should not be used again, they told PCIJ, “because it did not make the voting process quicker but instead slowed it down due to malfunctions.” In the EBAD report, election officers were also asked to provide specific recommendations in favor or against the use of the VRV system in the 2022 elections.

Other Comelec insiders offer qualified support for the VRV system, saying that while it should be used again, “the system should be improved and enhanced.” They said that rigorous testing should have been done on the integrity of the software and durability of the hardware, more comprehensive training conducted on the VRVM functionality, and “more efficient and responsive technical support system provided by the contractor” to address operational and troubleshooting procedures.

These insiders also proposed that VRVM technicians be under Comelec’s employ so they could be held more accountable. The VRVM should be made more user-friendly and straightforward, they added.

Service provider

The VRVM contract had been awarded to a joint venture of NextIX, Inc. and Gemalto Phils., Inc. on Dec. 4, 2018, or a mere five months before the polls. Neither company has responded to PCIJ’s queries as of this writing.

According to Gemalto’s 2016 general information sheet, nearly all or 99.99 percent of the company’s stocks are owned by Gemalto Holdings Pre Ltd., a Singaporean firm that is engaged in providing microprocessor cards and supplier of point-of-sales terminals, software, and service. Gemalto’s mother company is an Amsterdam-based digital security company with the same name.

A part of the French Thales Group, the Dutch Gemalto provides software applications, secure personal devices such as smart cards, and other services. It has supplied e-passports, driver’s licenses, and citizen IDs to various countries around the world. In September 2018, Estonian authorities filed suit against Gemalto to collect up to 152 million euros for alleged security flaws in citizen ID cards that the firm produced. Gemalto also figured in a 2010-2011 hacking incident related to SIM cards it had manufactured, which was reported and confirmed only in 2015.

Back in this country, the joint venture of NetIX, Inc. and Gemalto Pte. Ltd has also submitted to the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) the lowest calculated bid for the supply, delivery, and managed services of registration kits to build the Philippine Identification System (PhilSys), or the national ID system that would capture “cradle to grave” information on citizens in a national database.

The second lowest bidder for the PhilSys project is Dermalog, also a Gemalto partner in a contract that had been bidded out earlier by the Land Transportation Office (LTO), according to a recent Philippine Daily Inquirer report.

Who own Gemalto?

Of Gemalto Phils., Inc.’s five other nominal shareholders, two are foreign nationals: Michael Au (Canadian) and Lim Pei Ee (Singaporean). Both Au and Ee are based in Singapore. The rest are Filipinos: Samson Uy Ching, Magilyn T. Loja, and Abelaine T. Alcantara.

Based in Makati City, Gemalto Phils., Inc.’s primary purpose is to engaged in “manufacturing, customizing, importing, exporting, buying and selling, distributing, promoting, designing, developing, purchasing, maintaining, planning, assembling, installing, marketing at wholesale of all kinds of customized computer applications, software and hardware used for electronic data processing and storage, as well as all kinds of smart cards, magstripes, card personalization and related services, smart card related products and applications, hardware, software, system, capabilities in relation thereto and goods, machines and property of every kind of description used or useful in connection therewith.”

NextIX meanwhile is a family-owned company based in Cebu City. Registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on Aug. 31, 2005, NextIX is engaged in the business of researching and developing internet-based communication devices. It also acts as an agency in rendering telecommunication services.

On its own, Gemalto is considered a foreign supplier by Philippine law because it is an entity where Filipino ownership or interest is less than 60 percent. There are several preconditions that a foreign bidder must meet before it is allowed to participate in a bidding. In the case of the Voter Registration Verification Project or VRVP, Gemalto became eligible because it went into a joint venture with a Filipino company.

Under the 2016 Revised Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act No. 9184, among those eligible to bid for the supply of goods such as the VRVMs are persons or entities forming themselves into a joint venture in which Filipino ownership or interest is at least 60 percent.

A copy of the agreement between Gemalto and NextIX shows that the stake of NextIX in the joint venture is 60 percent while Gemalto’s is 40 percent. According to the document, NextIX is the “principal Partner” and the “Venture Manager.” Among the responsibilities of the latter are negotiating for the terms of any contract, as well as incurring obligations and receiving instructions for or on behalf of the joint venture. The joint-venture agreement was signed by NextIX CEO Roberto Jesus A. Suson and Gemalto’s authorized signatory Clarisse Gazzingan Cayetano on Nov. 27, 2018.

Prior contracts

A review of bid and award data from 2000 to March 2019 published by the Philippine Government Electronic Procurement System (PhilGEPS) shows that Gemalto had one previous government contract: the “Production, Personalization and Delivery of 600,000 Pieces Europay, MasterCard and Visa (EMV)-Compliant Cards” for the head office of the Development Bank of the Philippines. The contract worth PhP27.8 million was awarded on June 22, 2016.

PhilGEPS data also show that NextIX had won contracts from six government agencies and a local government unit worth a total of PhP80.6 million from 2012 to 2017. These agencies include the Department of Social Welfare and Development, Department of Trade and Industry, Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Philippine Postal Corporation, National Printing Office, Development Bank of the Philippines Data Center Inc., and the City of Makati.

In addition, PhilGEPS data show a 2017 contract won by NextIX with the Land Transportation Office for the procurement of the driver’s license cards with five-year validity. The contract, worth PhP829.67 million, is the single largest completed deal of NextIX with a government agency, and is more than 50 percent of the ABC of the VRV project.

As part of the bid requirements for the VRV project, the joint venture between Gemalto and NextIX submitted a certificate of acceptance and other supporting documents from the Commission Electorale Nationale Independent of France showing that Gemalto had a contract with the latter relative to its project for revision of electoral file in the amount of US$29.08 million or equivalent to PhP1.285 billion based on exchange rate in 2015, when the deal was signed.

Yet separately, NextIX and Gemalto would not have passed the Net Financial Contracting Capacity (NFCC) requirement as their respective financial position is far below the approved budget for the contract. To pass, the NFCC must be at least equal to the ABC.

Indeed, the latest financial statements available for Gemalto and NextIX show that the two companies’ finances might not have been sufficient to bid for a project worth almost a billion pesos.

NextIX’s current assets for 2014 for instance reached only PhP16.2 million, while its current liabilities stood at PhP11.4 million. Gemalto Phils. had current assets worth PhP67.6 million in 2015 and current liabilities at PhP46.4 million.

Even if the two companies have no ongoing contracts and were to bid for a project with a duration of more than two years, the maximum NFCC for NextIX and Gemalto would be at a mere PhP97.8 million and PhP423.9 million, respectively.

In the case of procurement of goods, however, a bidder may submit a committed Line of Credit from a Universal or Commercial Bank, in lieu of its NFCC computation. This is what Gemalto did.

The post-qualification report of Comelec’s Technical Working Group (TWG) shows that Gemalto submitted a Credit Line Certificate issued by Standard Chartered Bank and dated Sept. 6, 2018 in the amount of PhP117 million or equivalent to 10 percent of the ABC. The credit line was verbally confirmed to be valid by Standard Chartered through one of its trade services officer on Oct. 22, 2018.

Missing data

Two other companies had participated n the bid for the VRV project. According to an official report by the poll watchdog Legal Network for Truthful Elections (LENTE), right after the bids were announced, a representative for the potential joint venture of SMMT-TIM &Smartmatic, which would be among the losers, pointed out that the other bidders had failed to comply with Comelec’s instructions. Apparently, they had provided only bid amounts that excluded the option to purchase. Gemalto’s counsel and the representative from another bidder, Dermalog, maintained that they had complied with the requirement by putting “COMPLIED” on the bidding forms. TWG’s examination of the forms submitted, however, revealed that no amount was indicated on these.

After careful deliberation by the Special Bids and Awards Committee (SBAC), said the LENTE report, the Committee’s chair, Director Julio Thaddeus Hernan, requested the representatives of Gemalto and NextIX, as well as Dermalog, to attest on their manifestations that, when or if Comelec decides to avail itself of the option to purchase, it would pay an amount of zero. Both bidders said yes, and all of the bidders signed the abstract.

Comelec’s TWG’s post-qualification report shows that the Gemalto-NextIX joint venture complied with the specifications, but several items were marked‘**’ and ‘***.’ The note ‘**’ means “refer to bid docs” while ‘***’ means “subject to HAT (Hardware and Acceptance Test) after delivery (during contract implementation), including all other specifications that can be validated only during customization.”

Jimenez said that the Gemalto-NextIX joint venture passed post-qualification, which included a battery of tests involving the use of the system from start to finish. But he said that the bulk of the testing was done after the contract had already been awarded.– PCIJ, August 2019