By Karol Ilagan and Malou Mangahas

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Click to watch video

DAVAO CITY (PCIJ / 6 Sept) – For his home region and bailiwick of Davao Region, President Rodrigo R. Duterte gave the largest share of public works funds in the 2017 national budget, the first proposed and passed under his watch.

Duterte offered Davao or Region XI a dose of double love: PhP43.77 billion in infrastructure funds, a 119-percent increase or twice more than its PhP19.97-billion allocation in 2016. It was the first time since 2010 that Davao Region became the most favored with public-works funds of 16 other regions, excluding the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, which is not covered by data from the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH).

But a lot of money has not bought Davao a lot of finished projects. Senior officials and some contractors themselves trace the problem to a strange situation in the region: Mostly the same contractors are winning more and more contracts, grabbing more projects than they could finish well within their capability, and within deadline.

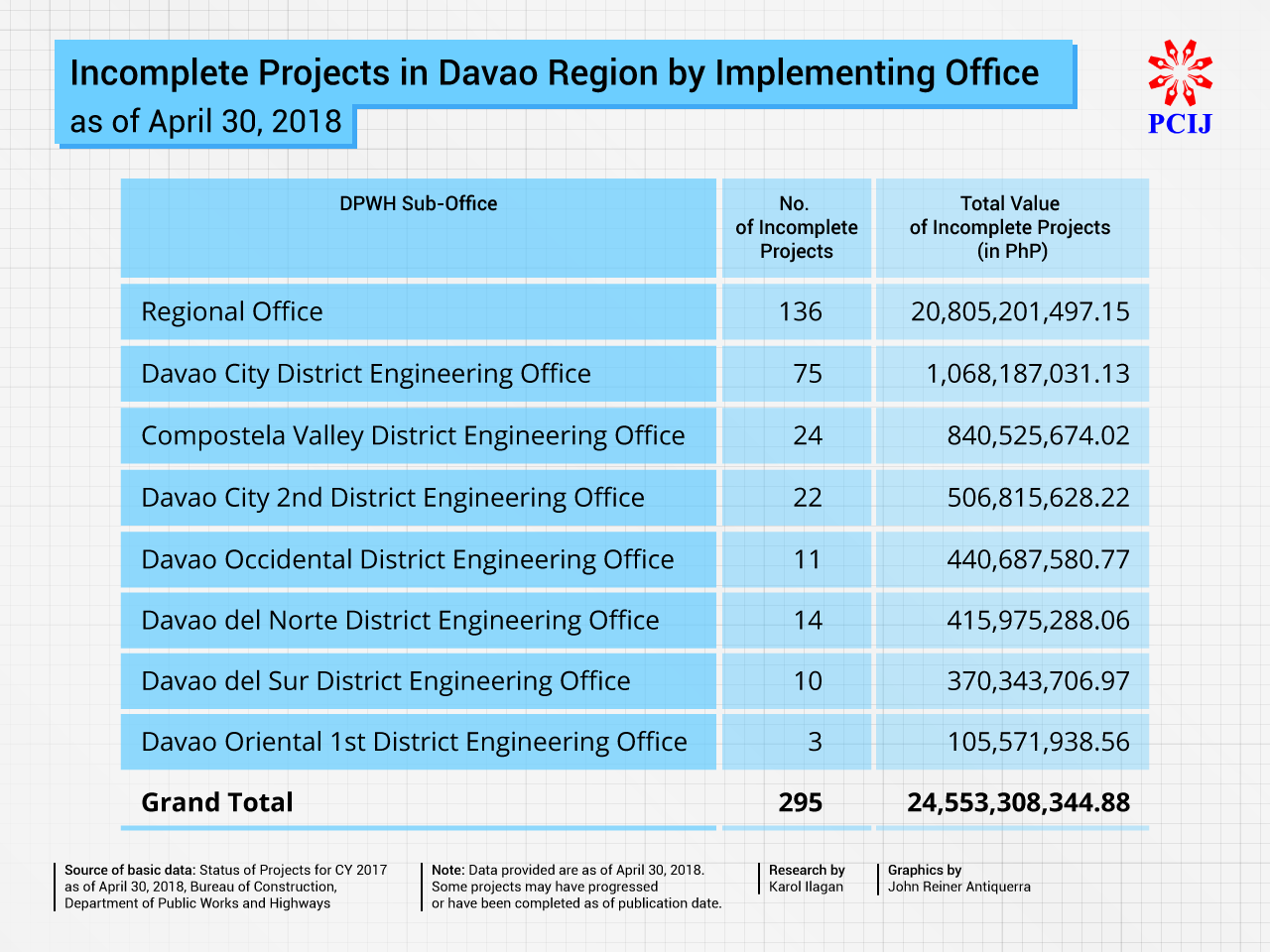

And so what should have been a blessing has turned into a curse for residents of at least two villages, Barangays Malugay and Mudiang in this city, where road projects remain unfinished eight months past their completion deadlines early this year. The projects are among 295 projects, out of 1,065 “total active projects” bidded out in 2017 in Davao Region that, by DPWH data as of April 30, 2018, remain unfinished past contract deadlines.

The unfinished projects, according to data from DPWH’s Bureau of Construction, altogether amount to PhP24.5 billion. This is equivalent to 56 percent if computed against Davao Region’s PhP43.77-billion public works funds in 2017.

These numbers do not look good at all. They raise serious doubts about the absorptive capacity of a region that suddenly has had to manage projects of value and possibly volume twice bigger than what it got a year earlier. (See Table: Incomplete Projects in Davao Region by Implementing Office, as of April 30, 2018)

Of the projects awarded in the region in 2017, at least 876 were still “ongoing” while three more have “not yet started” by the first quarter of 2018.

Thus, instead of comfort and ease, unfinished road projects here have decked the region with piles of dirt and rubble, daily showers of dust for motorists and residents, and occasional accidents on account of road obstructions.

Lucky set

There are still winners here, though. The financial bonanza from multibillion-pesos worth of projects in the region has benefited not only big contractors but also relatively smaller ones that, through a growing number of joint-venture agreements with the former, have managed to snare more and bigger projects.

To this lucky set of top contractors in Davao Region belong two entities owned by the father and the half-brother of Special Assistant to the President, Christopher Lawrence ‘Bong’ Tesoro Go: CLTG Builders and Alfrego Builders and Supply.

CLTG Builders stood out in PCIJ’s research because all of its joint-venture projects with big contractors in 2017 failed to complete projects by the original deadline. With just a B license, the firm could not have implemented the big-ticket projects it won in 2017 without having a partner.

The company that bears the initials of the presidential aide appears in Davao City’s 10 biggest contractors year on year from 2010 to 2017, according to DPWH data.

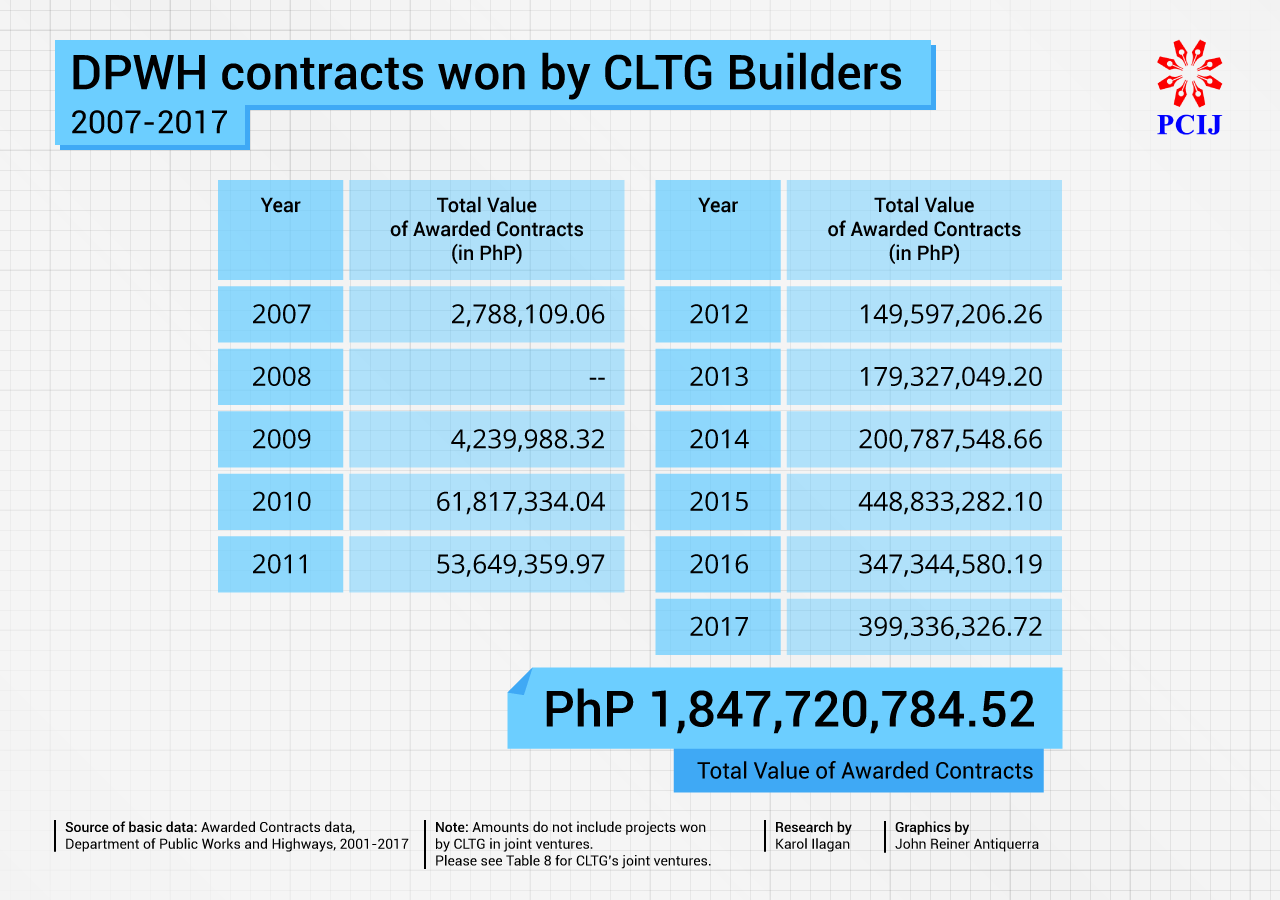

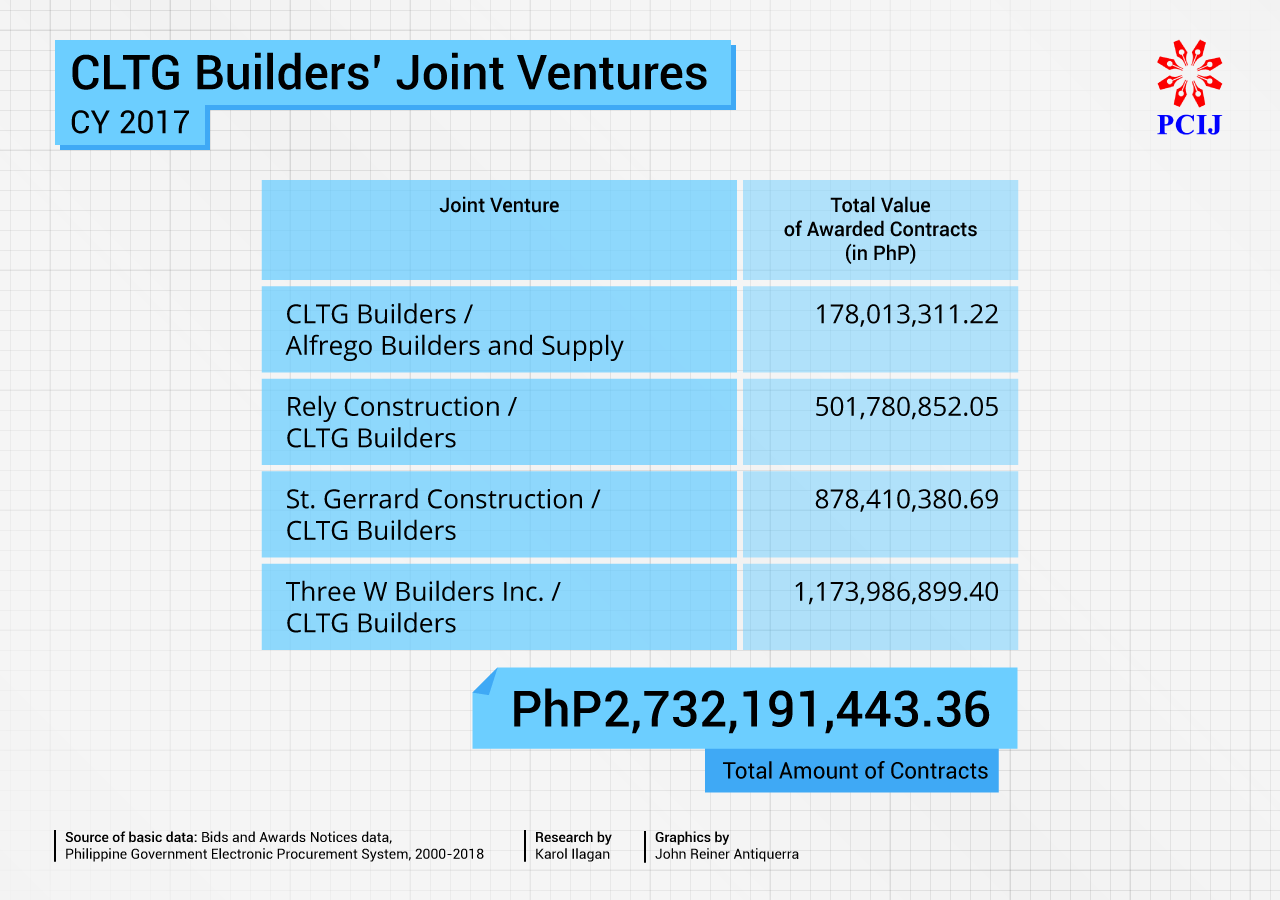

CLTG won a total of PhP1.85 billion worth of infrastructure projects for Davao Region from 2007 to 2017. This has yet to include the PhP2.7 billion worth of contracts won by CLTG through joint ventures with four other contractors, including Alfrego Builders, a firm owned by Bong Go’s half-brother Alfredo Go.

In sum, CLTG has been awarded PhP4.6 billion worth of projects, all from the DPWH, in the past decade. It won more than half of that total only last year, however. None of these projects has been awarded by the local government of Davao City.

Project status records

More money to spend means more work to be done. In Davao Region’s case, though, more money has also meant more work left undone, or a lot of unfinished projects.

Davao Region consists of the provinces of Compostela Valley, Davao del Norte, Davao Oriental, Davao del Sur, and Davao Occidental, and Davao City, which serves as regional center. Under Duterte who had served as Davao City mayor for 20 years, the region has assumed political preeminence bar none in the nation.

From the city and the region of Davao comes a powerhouse cast of power-wielders in the Duterte administration. They include Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez, Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea, dozens of political appointees in executive agencies and government-owned and -controlled corporations, and 11 district representatives, including former Speaker Pantaleon Alvarez, and Committee on Appropriations Chair Karlo Alexei B. Nograles.

Two other legislators from the region are vice chairpersons of the committee on appropriations, and the rest serve as chair, vice chair, or majority member of the equally significant committees on legislative franchises, constitutional amendments, small business and entrepreneurship, agriculture and food, East ASEAN Growth Area, and Mindanao Affairs. Apart from the DPWH Regional Office, the region has eight district engineering offices.

The projects status records of the DPWH’s Bureau of Construction show that as of April 30, 2018, Davao Region has 295 unfinished projects, including 136 or 46 percent bidded out by the DPWH regional office as implementing agency, and another 75 projects, by the Davao City District Engineering Office.

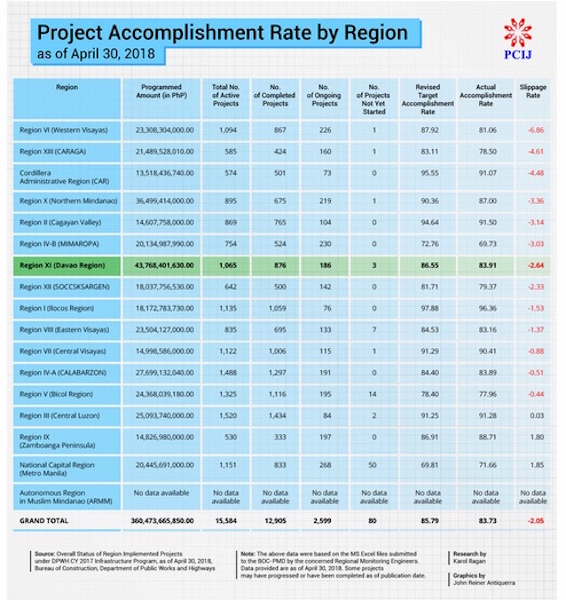

In its report on “Project Accomplishment Rate by Region, CY 2017,” DPWH said that Davao Region has a total of 1,065 “active projects,” including 876 projects “completed,” 186 that still “ongoing”, and three other projects that have “not yet started,” as of April 30, 2018. (See Table: Project Accomplishment Rate by Region, CY 2017, as of April 30, 2018)

Click to watch video

In contrast to Davao Region’s negative 2.64 slippage rate, three regions — Metro Manila, Zamboanga Peninsula, and Central Luzon — did not have project delays in 2017. The other regions with much smaller public-works budgets than Davao posted slippage rates of as low as negative 0.44 percent (Bicol Region) to as high as negative 6.68 percent (

But DPWH Region XI Chief Information Officer Gaudencio Ortiz does not seem to be worried. He said that the uptick in civil-works spending is meant to support the region as it has become a key economic player in Mindanao and the whole country.

“We are enjoying all this attention,” he said. “Therefore, we also have to keep up with that attention. We have to keep up with the development of the entire region, that is why there is this increase in demand for more infrastructure for the efficient delivery of goods and services.”

Unfinished projects

Residents of Barangay Malugay and Mudiang in this city would probably wish that DPWH focus its attention instead on rushing unfinished projects.

The road projects connecting the two villages have been awarded to the same contractor and implementing office: CLTG Builders and its joint-venture partner Three W Builders that won projects from the DPWH regional office.

In separate interviews, DPWH officials and CLTG’s owners cite the same reason for the project delay: the projects were bidded out even before road right-of-way (RROW) issues in the area had been settled.

CLTG Builders, a B-licensed construction firm, is owned by Deciderio L. Go, the father of Duterte’s special assistant Bong Go, while its JV partner Three W Builders is a Triple-A contractor from Las Piñas City.

Malugay and Mudiang are among the many villages in the eastern part of Davao City that are linked by an PhP852-million seven-package concreting and widening road project of DPWH Region XI. Five of those, Packages 1, 2, 3, 5 and 7, were awarded to CLTG and Three W Builders, while Package 6 was awarded to Wee Eng Construction. (PCIJ could not find Package 4 in DPWH and PhilGEPS records and during its field visit to Davao City.)

All the five packages assigned to the CLTG/Three W joint venture should have been done by February and March this year, but, by DPWH’s report as of April 30, 2018, remain still unfinished with 49 to 67 percent accomplishment rates only.

CLTG officers interviewed by PCIJ said that the projects are currently suspended on account of road right-of-way issues encountered during project implementation. DPWH Region XI, they said, is now trying to finish negotiations with affected residents.

Wee Eng’s part that is situated in Barangay Mahayag, meanwhile, is paved and clear and almost done at 96 percent.

PCIJ Photo/John Reiner Antiquerra

PCIJ Photo/John Reiner Antiquerra

Favored contractors?

Two senior government officials and at least four contractors privy to procurement activities in Davao told PCIJ in separate interviews that backroom deals are happening in order for certain companies to corner contracts even though they do not have the capability to take on projects.

The result is a rather skewed spread of infrastructure projects awarded to supposed favored and incapable contractors. The sources have all requested anonymity because of the potential implications on their employment and business.

DPWH officials and contractors alike point to one main reason as cause of delay for these projects: the acquisition of the road right-of-way. Although valid, acquiring RROW has been a longtime problem that has hindered many agencies in the past from implementing infrastructure projects.

What PCIJ also found in its analysis of official records and multiple interviews from sources is a story of individual firms and joint ventures, and an implementing agency with contracting loads that are much heavier than they used to carry, raising questions about their capability to complete the projects.

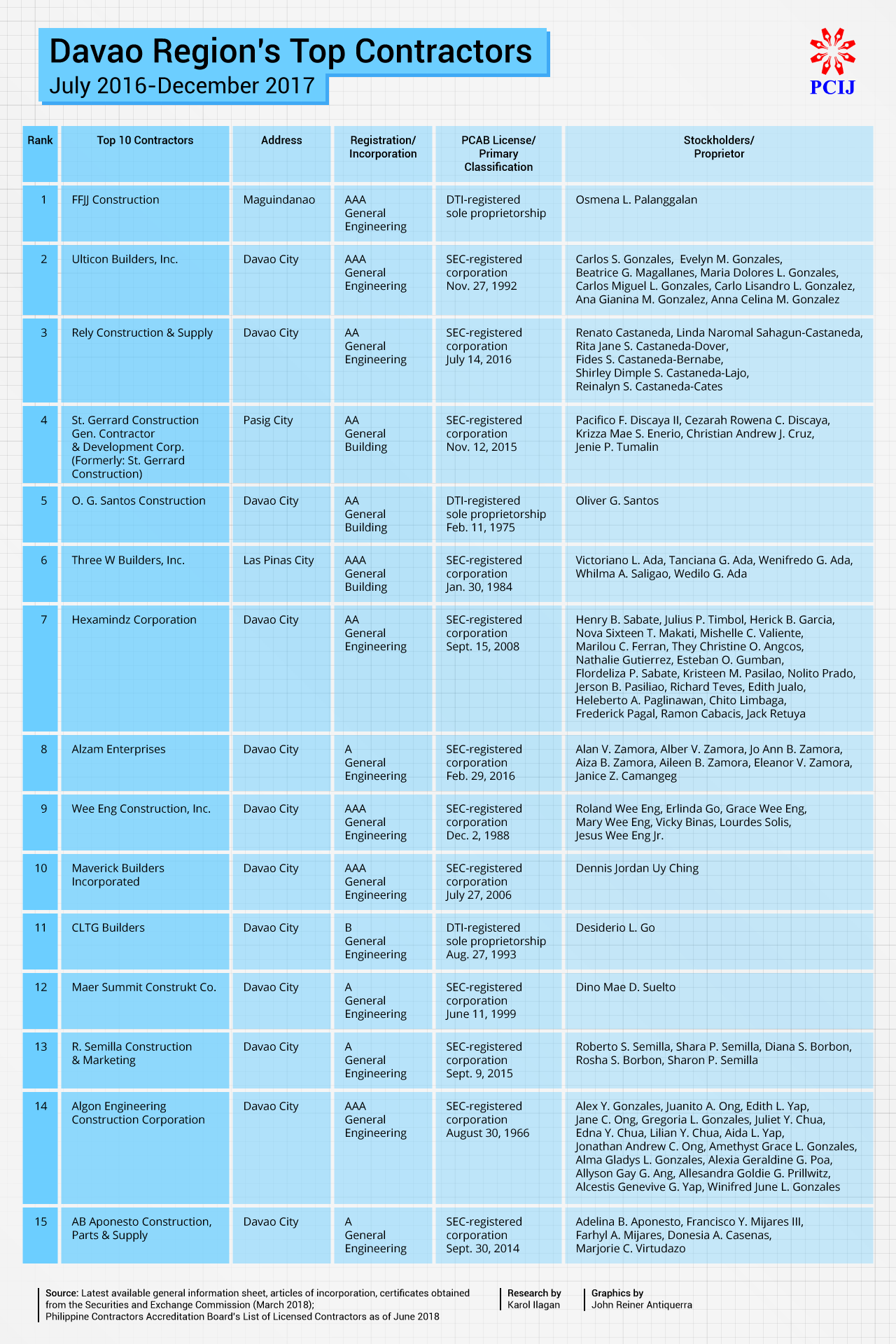

In fact, many of Davao’s and also the country’s top contractors are also on top of the list of contractors with the most number of delayed projects in the region. All of the contractors that had more than half a billion pesos worth of incomplete projects also belong among Davao’s top 15 contractors, from July 2016 to December 2017.

Leading this group are Ulticon Builders, St. Gerrard Construction, FFJJ Construction, Three W Builders, and CLTG Builders with more than PhP1 billion worth of delayed projects. They are followed by AB Aponesto Construction, Parts, and Supply, Rely Construction & Supply, and Wee Eng Construction. (See Table: Incomplete Projects in Davao Region by Contractor/Joint Venture, as of April 30, 2018)

Contractors’ replies

Of Davao’s top contractors, only Ulticon Builders, Wee Eng Construction, Algon Engineering Construction Corp, and CLTG Builders responded to PCIJ and gave reasons for the delay in their respective projects. Ulticon even refuted that it still had 24 delayed projects on account of the months that passed since PCIJ obtained the data from DPWH in early May 2018.

In a letter dated June 21, 2018, Ulticon’s Vice President for Operations Carlo Lisandro L. Gonzalez provided an updated status of the 24 incomplete projects in DPWH’s list. Four of the 24 projects have already been completed, Gonzalez wrote, while six have a 99-percent accomplishment rate. Three are ongoing, while the rest have either been suspended due to peace and order or road right-of-way issues or have just resumed operations since RROW problems have been settled, he also said.

Having multiple projects, Gonzalez wrote, is not the reason behind projects being incomplete. In Ulticon’s case, he said, there is no shortage in manpower or equipment to be able to finish the projects on time; the major problem that contractors like Ulticon encounter is road right-of-way. Gonzalez said that the DPWH is still negotiating with residents and owners of the area where Ulticon has suspended projects. He said that Ulticon “cannot continue with our operations using our maximum capacity without the necessary Permit to Enter or Writ of Possession.”

Wee Eng, meantime, confirmed that it had four delayed projects, all because of road right-of-way problems as well. But as of June 29, 2018, Wee Eng said, the Mahayag project has already been substantially completed and due for turnover. Two other projects meanwhile have been suspended while one is delayed in implementation.

Wee Eng Construction was started by Engineer Jesus Wee Eng in 1961 in Davao City as a single proprietor. Currently, Wee Eng has 250 to 300 employees in various projects. The company is also currently implementing 10 projects in Davao Region worth PhP1.17 billion.

“Having multiple big projects at a time do (sic) not pose problems to us because we only take on projects for which we are capable of doing simultaneously,” said Wee Eng manager Erlinda Go in a letter to PCIJ. “But oftentimes, RROW problems arise, which are beyond our control. This causes delay in our project implementation.”

Algon’s Operations Manager Manuel Gonzaga, meanwhile, said that the company’s bridge-widening project, which was at 89-percent completion as of April 30, 2018, was already finished on June 15, 2018. Also writing in reply to PCIJ, Gonzaga said that Algon’s other incomplete project, the construction of the Pagan Pequeño Bridge 2, “has been experiencing road-right-of-way problems.” A joint-venture project with R.D. Policarpio & Company Inc., the project was at 56-percent completion as of April 30, 2018.

CLTG explains delay

Maritess ‘Ali’ G. de Leon, CLTG’s quality management representative, said that the Malugay and Mudiang projects have been suspended in 2017 due to road right-of-way problems, and DPWH up to now is still negotiating with property owners. De Leon is the second of three children of Deciderio and the younger sister of Bong Go.

In an interview with PCIJ along with other CLTG officials, de Leon said that the situation is beyond the company’s control: “Gustuhin mo mang matrabaho eh hindi pa nila matapos negotiate sa may-ari. Ang tagal (As much as we want to work [we can’t] because they have not finished negotiating with the owner. It’s taken time).”

Asked why CLTG bidded for projects with unsettled right-of-way issues, de Leon said that this kind of problem only comes up once implementation begins. CLTG, she said, won the Mahayag and Mudiang projects unaware that RROW problems would occur. According to de Leon, RROW acquisition is under the purview of DPWH.

Ruth Rodriguez, CLTG Builders’ operations manager, for her part, said that a contractor may inspect the location before bidding, but it cannot tell whether residents would be amenable with the negotiations.

De Leon said that another reason for the project delays is that there are only few assessors for the multiple road projects being implemented across the country. Acquisition of RROW usually becomes an issue when the owner does not agree with the price being offered, the owner is either overseas or dead, disagreements among siblings who own the property, and the like.

In some cases, de Leon explained, some contractors have opted to negotiate with and advance payment to property owners to be able to jumpstart work on their projects. The advanced amount commonly referred to as tapal or abono is then reimbursed from the DPWH. De Leon said that CLTG only does this with owners who have complete papers because DPWH is quite strict with documentation.

At losing end

“Hindi mo talaga mapagalaw ang property hangga’t walang pera (You cannot really do anything with the property until money has been paid),” said de Leon. “’Yung mga tao sinuswelduhan na eh di losing end talaga ang contractor kaya sige tapalan na lang namin para na lang may matrabaho (We have to pay workers their salaries and the contractor is really left at the losing end. That’s why we pay first just so we can work).”

She said that while it may look like CLTG has abandoned the road project, most people do not know the real story behind its delay. CLTG precisely wants to complete the project, she said, otherwise it will not be able to collect full payment from government.

De Leon also noted that unfinished projects may cast a shadow on CLTG’s name, hence, “hindi puwedeng hindi tapusin, hindi puwedeng hindi gawin kasi ikaw rin ang maiipit (you can’t not finish the project, you can’t not do it because you will be the one in trouble in the end).”

All three CLTG officers who met with PCIJ last Monday invariably stressed that Bong Go had nothing to do with the company’s luck in winning projects. CLTG got more projects in 2017, according to de Leon, because of the bigger budget allotted for Davao Region but for the same number of contractors.

CLTG, which Deciderio Go said was put up and registered as a single proprietorship on Aug. 27, 1993, reportedly used to be able to bid for projects with the Davao City local government unit. But since Bong Go became Duterte’s assistant, the company stopped all transactions with the LGU. The CLTG officials at the interview all said it was Bong Go who specifically told them to stay away from city hall. This led CLTG to shift its focus to DPWH.

Rodriguez said that Bong Go has no role at all in CLTG and is unaware of projects it is implementing. “Walang role (No role),” she said. “Wala nga siyang alam kung ano ang project namin (He is not even aware of CLTG’s projects).”

DPWH on CLTG

DPWH officials say that CLTG and Alfrego have a history of implementing projects in the area and have not been favored in any way. For one, Ortiz of DPWH Region XI said, DPWH treats all contractors the same. He also said that the construction companies now winning contracts have existed even before Duterte became president.

“So, they have been winning contracts, they have been doing projects, so, if they qualify why not, ‘di ba?” Ortiz said. “Because they all go through the same process. If they win the bidding, if they qualify for the project, then we cannot do anything about it anymore because we are mandated by law.”

DPWH spokesperson Anna Mae Lamentillo in an August 2018 interview echoed Ortiz’s view. She said that DPWH follows the procurement law and is legally barred to disallow contractors from participating in any bidding procedures. “So kumbaga (in other words), si CLTG, we can’t stop them,” she said. “We are prohibited by law to do that. They’re qualified to join government procurement procedures.”

‘No human intervention’

Lamentillo said that the procurement process was crafted in such a way that bidding procedures are done without human intervention. “So all contractors can actually participate in the bidding process and if they win, they win it because of the process,” she said.

To be sure, contractors cannot be barred from bidding without cause. PCIJ then asked Lamentillo if DPWH is not one bit concerned about the allegations and whether it cannot take any initiative to look into the matter. She agreed that the allegations about CLTG’s activities are serious, and said that a formal protest mechanism provided by law is a recourse.

“I don’t think we want DPWH to intervene in the procurement process,” she also said. “I mean, it should flow as the process itself. It’s mandated by law. We follow certain rules and regulations.”

“We are open to investigating any issue in DPWH but file a protest first,” she added.

No ‘conflict of interest’?

Section 47, Rule XV of Republic Act No. 9184 or the Government Procurement Reform Act requires bidders to submit a sworn affidavit that it is not related to the head of the procuring entity, members of the Bids and Awards Committee, the Technical Working Group, and the Bids and Awards Committee Secretariat, the head of the project management office, or the end-user or implementing unit, and the project consultants, by consanguinity or affinity up to the third civil degree. Failure to comply with the provision shall be grounds for the automatic disqualification of the bid.

PCIJ does not have information linking CLTG to members of the DPWH offices in Davao. For instance, Davao City 1st District Engineering Office’s list of Bids and Awards Committee members from 2010 to 2016 does not have anyone whose surname is “Go.”

In an interview with PCIJ, Secretary Go said that he will resign if any information is found that he intervened in any way for his father’s contracting firm to get a project.

DPWH Secretary Mark A. Villar told PCIJ that he has not received any calls from Go asking for any favors for any project. He is not aware, Villar said, of any reports about CLTG and its activities in Davao.

Same as before

Gene Lozano, district engineer at the Davao City 2nd District Engineering Office, meantime said that even before he heard about Bong Go, he already knew of CLTG as a contractor. “Wala namang nagbabago kung ano ba ‘yung aming pakikitungo (Nothing has changed in the way we deal with them),” he said. “Before and now is just the same. Kung trabaho, trabaho (Work is work).”

Lozano also said that he has never been in touch with Bong Go. He might have met the father Deciderio, the engineer said, but the family never asked any favor from his office. “We never hear from them, hindi nga kami kilala (they don’t even know us),” he says.

District Engineer Wilfredo Aguilar of the Davao City 1st District Engineering Office also said that Bong Go never meddled with his father’s business. The only time Bong Go called him, said Aguilar, was to relay instruction from the president about an idle project he saw in Davao. He added, referring to CLTG, “Actually, before Bong Go was (assistant) ni Presidente, andiyan na ‘yan sila. Regular contractor na ‘yan. Hindi contractor na pipitsugin, talagang mga big time na ‘yan sila. Na-timing lang ngayon siyempre nakapuwesto (Actually before Bong Go became the President’s assistant, they were already there. They were already a regular contractor. Not a small-time contractor, they were already big time. It’s just that now [Go] is in an important post).”

Joint-venture projects

Davao Region’s No. 1 contractor from July 2016 to December 2017 was actually FFJJ Construction, a Maguindanao-based single proprietorship owned by Osmeña Palanggalan. According to procurement experts, it is not unusual for contractors, even the large ones, to operate as single proprietorships. Many of Davao’s and even the country’s major road project contractors are sole proprietorships.

A procurement expert working in government also says that big contractors need not necessarily incorporate, although care must be taken when taking on projects that are beyond a contractor’s financial and technical capacity.

CLTG started small with a capitalization of PhP3 million and six employees, according to PhilGEPS records. Today CLTG has at least 14 named employees occupying positions in the company’s Equipment, Engineering, Administration, and Continual Improvement divisions. The company also has unidentified backhoe/dump truck operator-drivers, maintenance staff, construction laborers, internal auditors, company drivers, and a warehouse man, according to an organizational chart hanging in the vacant lot next to CLTG’s home-office that doubles as a parking area.

Beyond NFCC

At least according to PhilGEPS records, CLTG Builders started implementing government projects in 2007 with a single PhP2.78-million project for the improvement and concreting of Eden-Tagurano Road in Toril District in Davao City. In 2009, it won two projects worth a total of PhP4.23 million for the concreting of Buhangin-Tigatto Road and the construction of a multi-purpose building in Bunawan Aplaya, Davao City.

Since 2010, CLTG’s project portfolio has been growing every year, reaching a peak in 2015 when it won PhP448.8 million worth of projects. (Duterte was mayor of Davao City from 2013 to 2016, replacing his daughter Sara who served from 2010 to 2013. Before Sara, Duterte was also mayor from 2001 to 2010 and 1988 to 1998.)

From 2007 to 2016, all of CLTG’s projects were below PhP50 million each. It was in 2017, the same year when Davao’s DPWH budget doubled, when CLTG began taking on projects that are beyond its individual contracting capacity.

Of the top 15 contractors in the region, only CLTG has a B license issued by the Philippine Contractors Accreditation Board (PCAB) since at least 2010. The rest either hold a Single A, Double A, or Triple A license. The highest license that can be obtained is Quadruple A.

Holding a license category “B” and a size range of “Medium A” for road projects, CLTG must have completed a single largest project worth above PhP10 million to PhP50 million and is allowed to take on projects of up to PhP100 million.

CLTG on its own then would not have been able to take on the PhP2.7 billion worth of projects it won from DPWH Region XI in 2017. Sixteen of those 18 projects were more than PhP100 million each, higher than the cost of projects CLTG is allowed with its B license and Medium A size range.

Too, the required Net Financial Contracting Capacity (NFCC) for such big projects would have been difficult to achieve given CLTG’s financial position and contracting load at the time.

Procurement rules require bidders to have an NFCC that is at least equal to the approved budget of the contract (ABC) or a commitment from a Universal or Commercial Bank to extend a credit line in favor of the prospective bidder if awarded the contract to be bid.

The NFCC is computed as follows: NFCC equals current assets minus current liabilities, multiplied by variable K, then less the value of all outstanding works or projects under ongoing contracts, including awarded contracts yet to be started. Variable K is 10 for a contract duration of one year or less, 15 for a contract duration of more than one year up to two years, and 20 for a contract duration of more than two years.

18 joint-venture deals

In 2017, CLTG won three individual projects and 18 projects with joint ventures. By April 6, 2017, CLTG had already won contracts worth PhP976,959,745.11. By then, PCIJ estimates indicate that it would have been unable to take on more projects because its NFCC would have been in the negative.

CLTG’s financial records obtained from PhilGEPS on June 22, 2018 show that CLTG’s current assets were valued at PhP88,941,029.35 and its current liabilities at PhP873,408.76, as of 2016. If these figures were used to calculate CLTG’s NFCC by April 6, 2018, the result would be

-PhP96,283,539.21. The calculations look like this:

[Current Assets (P88,941,029.35) – Current Liabilities (P873,408.76) X K (10 for projects with a contract duration of one year or less)] – Estimate value of all outstanding works or projects under ongoing contracts (P976,959,745.11) = negative P96,283,539.21

The succeeding two projects that CLTG won after April 6, on April 10, were worth PhP87.2 million and PhP128.4 million each, or more than its estimated NFCC at the time.

To upgrade license

But what CLTG did in 2017 to get more of these projects was to team up with other bigger contractors to meet contracting capacity requirements of the DPWH Region XI’s bigger projects. CLTG engaged in joint ventures with two Davao-based contractors — Alfrego Builders and Rely Construction & Supply — and two Metro Manila-based firms, St. Gerrard Construction and Three W Builders. The projects in Malugay and Mudiang are CLTG’s joint-venture projects with Three W Builders.

Rely Construction, St. Gerrard Construction, and Three W Builders are among the Top 10 contractors in Davao, which means that they too, have multiple and big projects on their own.

CLTG’s Rodriguez said that the company decided to engage in joint ventures because it wanted to qualify for bigger projects and earn more experience to be able to upgrade its license and contracting limit. She said that they knew about Three W and St. Gerrard because they too implement their own projects in Davao.

Two procurement experts interviewed separately by PCIJ agreed that a contractor may indeed enter into a joint venture with another contractor when capacity is already inadequate. But, they both noted, simultaneous projects that contractors are implementing as individual contractors and as a joint venture must also be considered if they qualify in new projects with their capacities pooled.

One of the experts who currently works in government said that care should be given in the validation of the key personnel to be assigned in the context of other projects to be implemented simultaneously. After all, the expert said, the same technical personnel could be pledged for several simultaneous projects. If their assignment in every project is a full-time job, said the expert, then they cannot be in two projects or more at the same time.

The same would be true for equipment committed for the project and other projects implemented simultaneously, the expert said. Moreover, the financial capacity has to be checked in terms of the NFCC considering other projects to be implemented simultaneously.

The CLTG officials interviewed by PCIJ could not give an estimate of how many employees the company has in all. But they said that the firm has one engineer per project. De Leon said that they do not take on projects they cannot finish and has not had any record of not completing a project. “We can look (you) straight in the eye and say kaya (it’s doable),” she said.

More projects delayed

CLTG’s joint venture partners – Rely, St. Gerrard, Three W, and Alfrego – all have their own individual projects and joint ventures with other contractors. These projects are also on the list (add link to PDF file) of DPWH’s unfinished projects as of April 30, 2018.

Rely Construction, for instance, won PhP3.9 billion worth on DPWH contracts during Duterte’s first 18 months as president, from July 2016 to December 2017. CLTG is not the only partner of Rely in Davao; Rely also has joint ventures with C.T. Leoncio Construction & Trading, Alonzo Construction, Alfrego Builders & Supply, Astrobuilt Construction & Development, and Hi-View Resources & Development. All of these joint ventures have incomplete projects; Rely on its own has unfinished projects as well.

A Double-A, SEC-registered corporation, Rely’s current assets as of 2016 was at PhP311.1 million and current liabilities at PhP81.6 million.

PCIJ visited Rely’s office at the Panorama Summit hotel along Tigatto Road, Buhangin, Davao City to seek comments from its manager Renato Castañeda, but he was not in the office at the time. PCIJ’s inquiry letter has yet to be addressed by the contractor as well.

No. 1 contractor in PH

St. Gerrard, meanwhile, is not just one of Davao’s top contractors; it is the No. 1 contractor in the entire country with PhP12.3 billion worth of projects from July 2016 to December 2017. Based in Pasig City, St. Gerrard is a Double-A contractor registered with the SEC. As of 2016, St. Gerrard’s current assets stood at PhP2.85 billion and current liabilities at PhP9.88 million.

Like Rely Construction, St. Gerrard has several joint-venture partners in Davao apart from CLTG. It has joint projects with Hi-View Resources & Development Corporation, Maer Summit Konstrukt Co., TKS Builders & Supplies, and Digos Tesston Const. & Supplies, all of which have incomplete projects as of the end of this year’s first quarter.

PCIJ has yet to receive St. Gerrard’s response to its letter dated June 27, 2018 despite multiple follow-ups with its owner Pacifico Discaya II.

Three W Builders also has partnerships with several contractors in the region: Tagum Builders Contractors Corp., TKS Builders & Supplies, Davao Rock Mixer Enterprises, and Ecomixed Construction and Development Corporation. These partnerships, like those with Rely and St. Gerrard, have a long list of delayed projects as of end of April this year.

Three W Builders is a Davao top contractor with PhP2.04 billion worth of projects. It is No. 13 by value of contracts won nationwide. Registered with the SEC in January 1984, Three W Builders is a Triple-A contractor with current assets of PhP66.5 million and current liabilities of PhP1.27 million as of 2016.

Three W Builders has also yet to respond to PCIJ’s letter dated June 27, 2018.

Bong Go’s half-brother

Alfrego Builders is the smallest among CLTG’s joint-venture partners. A single proprietorship, Alfrego has a D license. Its current assets, as of 2016, were valued at PhP55.86 million, and current liabilities, PhP22,896. The company’s property and equipment were worth PhP7.9 million during the same period.

From 2005 to early 2016, Alfrego won PhP88 million worth of projects. In 2017, it joined up with CLTG, Triple-A contractor FFJJ Construction, and Double-A contractor Rely Construction to carry out projects wort

Alfredo Go, owner of Alfrego and half-brother of Bong Go, told PCIJ that project redesign, apart from peace and order and weather, is another issue that causes delay. This, he said, is the reason why Alfrego’s joint-venture project with CLTG has been delayed.

The Alfrego/CLTG joint venture was awarded two packages of a bypass-road reconstruction and widening project worth PhP91 million and PhP89 million, respectively. Both projects were at 53 percent and 60 percent accomplishment rate, as of April 30, 2018.

Monitoring JVs

DPWH officials in the region said that apart from being able to qualify for bigger projects that are beyond one’s capacity, a contractor goes into a joint venture to earn experience to increase one’s capacity for future projects.

Ortiz said that going into a joint venture with a higher-category contractor will sort of serve as a stepping stone for an individual to get higher contracts in the future. Joint-venture agreements for small-category contractors encourage them to “step up” their game and enable them to be able to compete with large contractors, he said.

Gene Lozano, district engineer at Davao City 2nd District Engineering Office, also said that contractors will earn experience from joint ventures that will help them increase their limit. He said, “Kaya ayun nga ‘yung advantage ng joint venture. Mabilis ‘yung increase of their limits, yung category nila (So that’s the advantage of a joint venture. They can quickly increase their limits, elevate their category).”

In theory, a joint venture or having two or more contractors working on a single project can ensure that a huge project will be successful. In reality, however, such joint ventures for the most part have been problematic.

Legal loophole

Several contractors interviewed by PCIJ on the condition of anonymity said that joint ventures have provided a legal backdoor for smaller contractors to win big projects that they would not have qualified for on their own by “using” or “borrowing” the license of a bigger contractor. On paper, both contractors are supposed to implement the project, but in reality, only the small contractor gets the project and implements it. A “royalty fee” fee worth two to five percent of the contract amount is paid to the big contractor for “lending” its license.

A Triple-A contractor said that these arrangements are most obvious in joint ventures where the “authorized managing office” is the representative of the small firm and not of the big firm. This, he said, is one of the reasons why some projects get delayed because the small contractor is simply incapable of implementing the project in the JV. The only reason the small contractor managed to “win” the project in the first place is because it had help from the big firm.

DPWH records show that joint ventures are also the ones with a significant number of projects left unfinished, leaving Davaoeños unhappy and inconvenienced for at least a year now. As of April 30, 2018, joint ventures have at least PhP6.6 billion worth of delayed projects in the region.

District Engineer Wilfredo Aguilar of the Davao City 1st District Engineering observed that joint ventures seem to have become a trend especially for big projects. He recounted, “May isang small contractor na gustong magpalaki, magje-JV sila, joint venture ng isang contractor. Ngayon, ang gumagawa ‘yung ka-JV (A small contractor who wants to take on bigger projects has a joint venture with a contractor. Now the one actually doing the JV is the other contractor).”

But the bigger contractor is not necessarily the one taking charge in a joint venture. According to Aguilar, this depends on the joint-venture agreement between the partners. Say, for instance, a smaller contractor’s NFCC is 80 percent of the project, he said. The smaller contractor may seek a partner that will take care of the 20 percent in order to be eligible for the project. If this joint venture wins, Aguilar said, the smaller contractor will represent the joint venture because it holds the bigger share in the project.

Asked about joint ventures involving a local contractor and another based in Manila like Davao-based CLTG with Pasig-based St. Gerrard and Las Piñas-based Three W Builders, Lozano meanwhile said that the local contractor may ask its partner to let it be the one to implement the projects. “Ako na lang ang gagawa, eh ‘di ayun, maggawa sila ng agreement… na siya ang authorized to do the project, to implement the project,” he says.

Tricky part

DPWH insiders admit, however, that the tricky part is that there seems to be no way for DPWH to know just how much each JV participant is actually contributing to a project, since a joint venture is treated as a single entity, supported by an agreement between two contractors.

Too, the partners might have made a financial arrangement in which the big contractor’s contribution is money while the small contractor takes care of the actual implementation of the project. In this case, only the small contractor will be seen doing work in project site.

Engineer Michael de la Vega of DPWH Region XI commented that joint-venture partners are considered one entity and that it depends on the contractor how they will share responsibilities as long as it fits within the project timeline. DPWH Region XI spokesperson Dean Ortiz also said that a joint venture has only one authorized manager or representative who is recognized by the agency. “So in this case we considered both contractors as one with that representative,” he said.

Asked about the capacity of a smaller but lead contractor to implement a project, which in the first place it could not have done alone, Lozano said that local contractors usually “have all the capabilities.” The local contractor, he said, has the resources but it may not eligible to join the bidding simply because it does hold the proper license category.

Then again, the category of PCAB license issued is based on the financial capacity, equipment capacity, experience of the firm, and experience of technical personnel of the contractor.

Cause for disqualification

Republic Act No. 4566 or the Contractor’s License Law provides that no contractor, including sub-contractors, shall engage in the business of contracting without first having secured the proper PCAB license. The law was enacted to ensure the safety of the public with having only qualified and reliable contractors are allowed to undertake construction in the country.

To Lozano, though, it all boils down to how interested each joint-venture partner is in implementing the project. As for his office, he said that its primary concern is that the project is implemented properly. “If you follow the specification or implement the project on time, wala tayong problema (we have no problem),” he said.

Similarly, Ortiz said that DPWH does not bother itself over which joint-venture partner is really doing the project, so long as this is delivered efficiently. He pointed out, “We consider it, both parties as one, so we only deal with one person. We only hold the representative accountable for that purpose. So, as long as they deliver the goods, as long as they deliver the project in the manner that they should, okay na kami doon.”

Asked why top contractors, including those in joint ventures, have the most number of incomplete projects, Ortiz said that he cannot answer anymore because he has no idea. Then he added, “Siguro if I talk more about it, I will be jobless starting tomorrow.”

DPWH spokesperson Anna Mae Lamentillo said that joint ventures are legally permissible. Only if there is a complaint can DPWH act and investigate, she said. “They (joint ventures) were created by law for certain type of situations,” she said. “As an implementing agency, we (DPWH) cannot amend it.”

But DPWH Secretary Villar’s legal advisor Pristine de Guzman said that misrepresentation in joint ventures is actually a ground for disqualification. For instance, she said that a joint-venture partner who is not actually participating in implementation is a misrepresentation on the part of the joint-venture entity.

“Kasi dapat sila, kung ano ‘yung ni-rerepresent nila, kung ano ‘yung capability nila and ‘yung sabihin natin ‘yung shares nila, dapat ganoon talaga (It should be that what they represented, what their capabilities are, and what they said their shares are, that would be how everything should really be),” de Guzman said. “And if it turns out na hindi (it’s not), then we will really appreciate kung may mga reports na ganoon para madali kaming mag-disqualify (if someone reports to us so we can easily disqualify them).” – With research by John Antiquerra, Carolyn O. Arguillas, Alyssa Rafael, Mildred Mira, Yzabel Layson, and Fern Felix, September 2018