KIDAPAWAN CITY (MindaNews / 22 May)—In my previous article I listed down some common aberrations in Kidapawan’s heritage—“cultural pollution,” I call them—which have been perpetuated as “traditional” when they are in fact recently fabricated novelties inorganic to the town’s cultures.

That was only one facet of the bigger problem of cultural and historical distortion in the Greater Kidapawan Area.

Another serious aspect of this can be rightly called “fake history”—the perpetuation of inaccurate or downright false historical information as “common knowledge” in the town’s understanding of its past.

In my work as city historian, this has been my biggest headache, as many of these “facts” are so long-held that people refuse to let them go. It has been particularly difficult to correct people in discursive authority—teachers, politicians, and journalists—as power seems to dissuade them from admitting error.

But correcting these errors, despite that resistance, is a major part of the job of a city historian, and I have both appeared in print and gone live on the local radio stations making these corrections.

I take the opportunity once again to point out those corrections here, subverting that insidious adage by Joseph Goebbels and hoping that a truth, too, when repeated often enough, could undo a widely believed lie.

1. “Kidapawan” does not mean “spring in the highland” – This etymology of the city’s name has been perpetuated for decades by no less than the local government, with official documents dating back to the 1970s citing it. The proposed breakdown of the word—“tida” for spring and “pawan” for highland—is purportedly in the indigenous Monuvu language. But anyone who speaks the language knows those words are gibberish. Correcting this was the main goal of my paper “Origins of the Toponym ‘Kidapawan’: A Reevaluation,” which was published on the Journal of Philippine Local History and Heritage in 2020. Although the paper, which presents several more plausible etymologies (“tiddopawan,” meaning “place of overflowing,” and “loppawan,” meaning “place of overcoming” being most likely), has now changed the local government’s official explanation, the local education system and the local media are a bit slower to catch up.

2. Kidapawan was never part of Pikit – Perhaps the most pervasive bit of historical error in the Greater Kidapawan Area (and indeed in North Cotabato) is this commonly held trivia that “Kidapawan was once a barrio of Pikit.” Kidapawan was already an independent municipal district, alongside Pikit-Pagalungan, by 1914, and would become a municipality in 1947, two years before Pikit was carved out of the Municipality of Pagalungan. There is no evidence that any portion of the Greater Kidapawan Area was ever part of the territory of Pikit, and there is ample evidence that it had always been a separate entity. If anything, tribal history among the Monuvu of Kidapawan has it that the area of Pikit—now traditionally Maguindanaon—was once Monuvu territory, but had been bequeathed (“id pikit” in Monuvu) to the Maguindanaon as part of settlement negotiations to end a precolonial war. That would make Pikit once part of Kidapawan. The idea that Kidapawan was once part of Pikit first appeared in print in the late 1960s (over two decades since the founding of the municipality), and may have stemmed from the fact that early colonial offices were in Pikit, creating the misconception that Kidapawan was Pikit’s barrio. In 2018 I had a public spat on a radio station with a local media man over this.

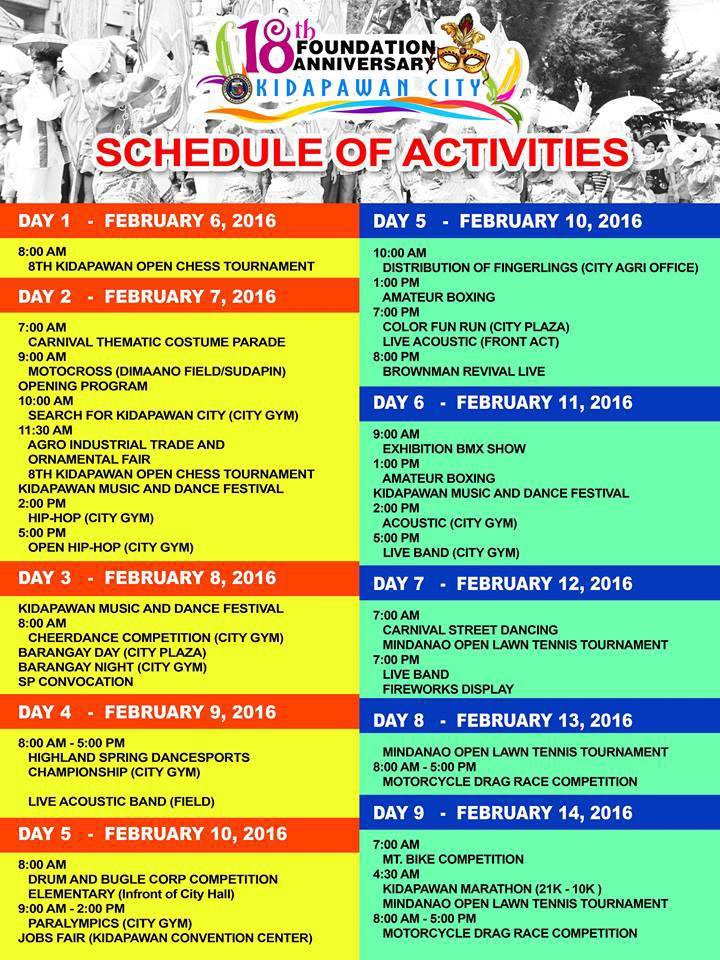

3. Kidapawan was not founded in 1998 – The local government is partly responsible for this, having for some time labeled 12 February (the date Kidapawan was chartered into a city in 1998) as “Foundation Anniversary.” There was for a time a dominant view that 1998 was the year Kidapawan was “founded,” and that the Kidapawan that came before it had been abolished. It was a view I had successfully fought against: the town has roots far deeper than cityhood, roots that were at risk of being ignored. Kidapawan was made a municipality in 1947, and before then it was created a municipal district by the Americans in 1914. Evidence suggests that it emerged as a coherent local political unit as early as 1908, when the Monuvu settlements in what would be the Greater Kidapawan Area fell under the oversight of the American client leader, Datu Ingkal Ugok. This would make Kidapawan over a century old.

4. Datu Siawan Ingkal was not Kidapawan’s first mayor – This might ruffle a few feathers (especially for those who will only read that sentence) but Datu Siawan Ingkal—who has often been cited as Kidapawan’s “first mayor”—never actually held the title of “mayor.” Kidapawan’s founding figure was his father, Datu Ingkal Ugok, Kidapawan’s first known official (the Americans are known to have given him the title “capitan” in 1908). In 1914, Siawan took over, being appointed “President” when Kidapawan was created into a municipal district. He was the only person to ever hold this title, and he held it until 1947 (over three decades) until he was elected Kidapawan’s first ever vice mayor. The first person to ever hold the title of “Mayor of Kidapawan” was Alfonso Angeles Sr.

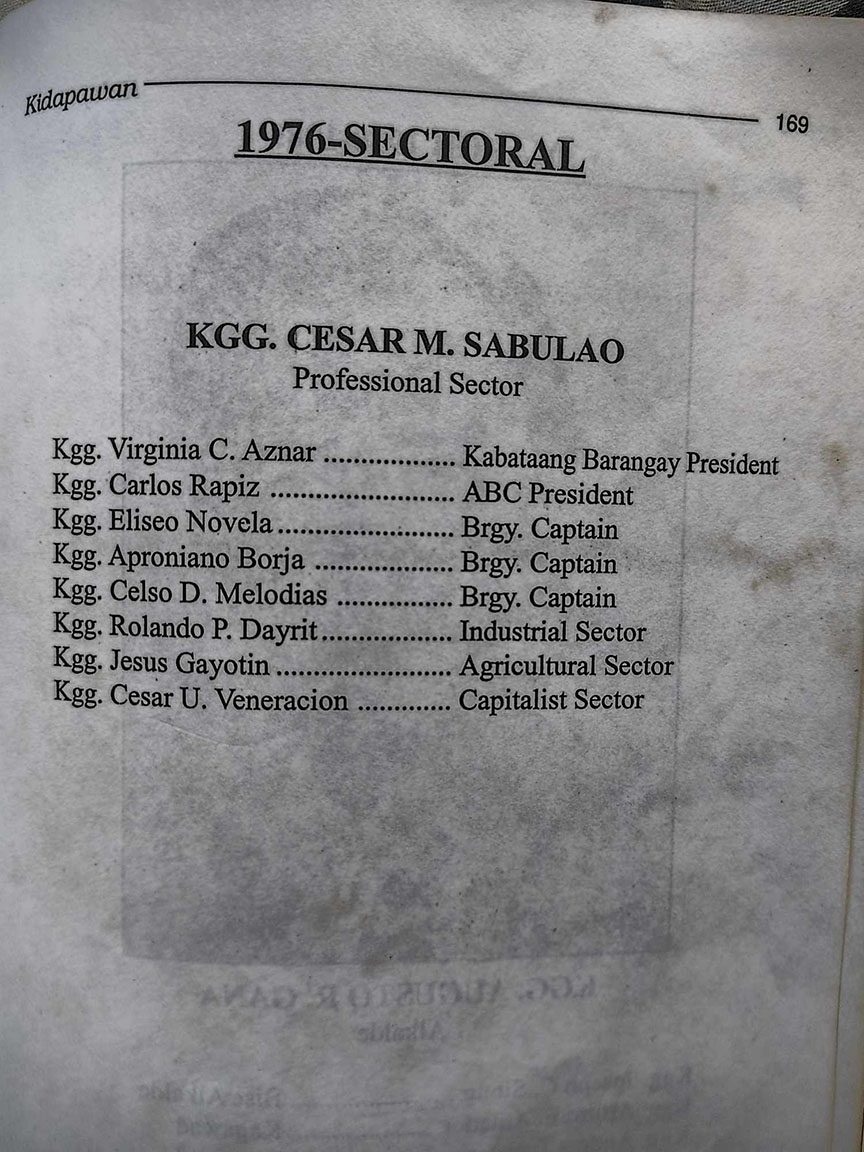

5. Cesar Sabulao was never Mayor of Kidapawan – The one responsible for this error is Ferdinand Bergonia, whose 2001 book “Lungsod na Pinagpala – Kidapawan” (the first book on Kidapawan history published by the local government) lists the late Dr. Cesar Sabulao as a mayor. The first to alert me of the error was Sabulao’s daughter, Dr. Cynthia Sabulao Asuncion, who was surprised when I arranged an interview in 2018 to talk about her father’s time as mayor. When I reviewed the minutes of the Municipal Council Sessions of 1976—the year Sabulao was supposed to have been mayor—I confirmed that he never held the title. What I did find was a souvenir program in 1999 which lists the sectoral councilors elected in 1976, to join the councilors elected in 1971 (at the time, Augusto Gana was mayor). I suspect Bergonia saw that Sabulao was on top of this list, and carelessly listed him as mayor.

6. No, Kidapawan was not peaceful under the Presidency of Marcos Sr. – People in Kidapawan tend to say when asked that Kidapawan was “relatively peaceful” under the Presidency of Ferdinand Marcos Sr., particularly in the years leading up to and following the declaration of Martial Law. But both the minutes of the Municipal Council Sessions and oral history (including accounts from survivors I have written about before) are replete with evidence that Kidapawan was in turmoil and experienced great violence from 1972 to 1985. Augusto Gana called several emergency sessions to discuss the municipality’s response to armed conflict spilling into the town. Gana himself was behind a lot of the violence, as these were the years his henchmen were in a prolonged armed standoff with the people of Datu Mambiling Ansabu and several settler families whose lands in Arakan Gana had grabbed to make his vast ranch. And I had written here earlier of the violence the town’s Moro civilians experienced under state-backed militias. Attacks on civilians by the New People’s Army (NPA) also took place around this time, most notably the massacre of the Ajeros on 27 January 1983. There was no golden era in Kidapawan to speak of.

(MindaViews is the opinion section of MindaNews. Karlo Antonio G. David has been writing the history of Kidapawan City for the past thirteen years. He has documented seven previously unrecorded civilian massacres, the lives of many local historical figures, and the details of dozens of forgotten historical incidents in Kidapawan. He was invested by the Obo Monuvu of Kidapawan as “Datu Pontivug,” with the Gaa (traditional epithet) of “Piyak nod Pobpohangon nod Kotuwig don od Ukaa” (Hatchling with a large Cockscomb, Already Gifted at Crowing). The Don Carlos Palanca and Nick Joaquin Literary Awardee has seen print in Mindanao, Cebu, Dumaguete, Manila, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Singapore, and Tokyo. His first collection of short stories, “Proclivities: Stories from Kidapawan,” came out in 2022.)

========================================

On this section of Moppiyon Kahi diid Patoy, we remember important dates and incidents that took place in Kidapawan history.

9 May 1936 – Commonwealth President Manuel Quezon declared portions of the municipal district of Kidapawan as part of the Mt. Apo National Park by virtue of Proclamation No. 59 of 1936.

12 May 1951 – Datu Bulatukan Lambac of Malasila would be appointed vice mayor of Kidapawan in the wake of Datu Siawan Ingkal’s resignation from the post.

16 May 1972 – the Cotabato Electric Cooperative (COTELCO) was set up in Kidapawan. It replaced the Kidapawan Electric and Power Corporation, which had been providing Kidapawan electricity since the 1950s.

19 May, 1981 – Alfonso Angeles Sr., Kidapawan’s first mayor, died of cardiac arrest, pneumonia, pulmonary complications, and emphysema at the now defunct St. Joseph Hospital in Kidapawan.