KIDAPAWAN CITY (MindaNews / 3 July)—This year, the Manobo Apao Descendants Ancestral Domain Claim of Mt. Apo (MADADMA) celebrates its 20th anniversary.

MADADMA is the ancestral domain claim organization that manages the large ancestral domain in the Kidapawan barangays of Ilomavis and Balabag and the Magpet barangay of Kawayan. It is the first ancestral domain claim in Kidapawan to be formally issued a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) under the terms of the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act, and one of the first in the country.

Members of MADADMA claim descent from Apao, the semi-legendary figure who in Monuvu oral tradition was the first person to climb Mt. Apo. Apao was the first to settle in the area, and he divided the land among his children based on landmarks and demarcations that have been passed down the generations. MADADMA’s current Council of Elders is in the fifth to sixth generation from Apao.

Although it is the oldest formally titled ancestral domain in Kidapawan, MADADMA is only one incarnation of the long history of indigenous land rights in Kidapawan. That history has yet to be formally written, but here I provide what may be considered a skeleton, for future writers (probably including me) to flesh out.

The very origins of Kidapawan, in can be argued, lie in land security for the Monuvu. Kidapawan’s first officials were tribal leaders, led by the Municipal District President, Datu Siawan Ingkal.

Oral tradition suggests Datu Siawan’s policy was to assimilate the Monuvu into coloniality to empower them, and this included making them educated enough to have their lands privately titled. This is why today Monuvu families in the downtown area have large tracts of formally titled land—the Icdangs, the Mundogs, the Guabongs among other families are owners of prime commercial and residential properties in the town.

This, however, was not consistently applied in the outskirts, specially near Mt. Apo. Monuvu families here found part of their ancestral land included in the Mt. Apo National Park (created in 1936), while others suffered from squatting by informal settlers, especially after the Second World War.

This was the experience of the descendants of Apao, who were also among the first to make a move to have their rights over their ancestral land formally recognized in a way different from private titling. I have yet to locate documents to shed further light on this, but the clan’s oral tradition has it that Datu Obun Umpan filed a petition before the Philippine President (identified as Ramon Magsaysay, putting it between 1953 and 1957) to release to the clan an area of around 1,500 hectares in the national park. The petition was ignored.

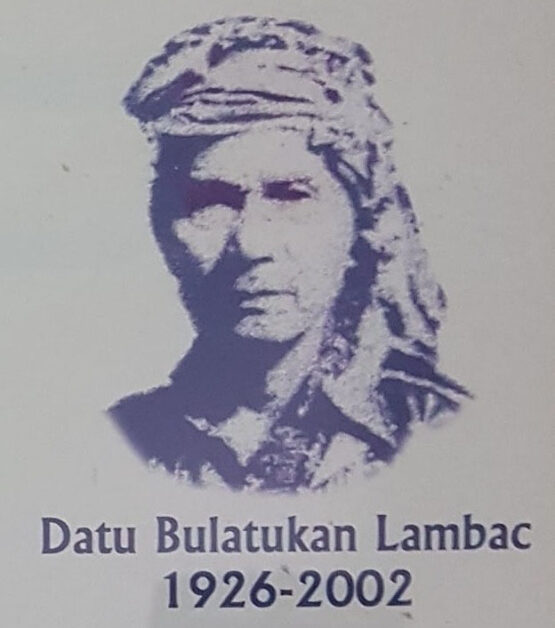

Around the same time, the Vice Mayor of Kidapawan, Datu Bulatukan Lambac, was also making moves to secure formal recognition of ancestral land. His first action as Vice Mayor was to sponsor the passage of Municipal Council Resolution No. 61 of 12 May 1951, petitioning the Secretary of Agriculture to designate 2,000 hectares in Malasila (now in Makilala but then in Kidapawan) as a Monuvu and Tagabawa Reservation. Like Datu Obun Umpan’s efforts, petition was ignored by the national government.

In other parts of the Greater Kidapawan Area, ancestral land ownership would become an issue as land grabbing became prevalent, especially during the turmoil of the Marcos era. The most prominent case was that of Katindu in what is today Arakan, ancestral domain of the descendants of Datu Ansabu. The mayor of Kidapawan, Augusto Gana, occupied vast tracks of Katindu from the late 1960s to the early 1990s and set up a ranch, displacing the Ansabu clan. Datu Mambiling Ansabu led a protracted armed struggle against Gana, but they also worked closely with the Catholic diocese of Kidapawan to fight a legal battle, a battle they eventually won. (Fr. Romeo Villanueva’s 1996 essay “Katindu: A Manobo Saga” gives detailed account of what happened, and how the church played a big part in helping the Ansabus).

Among the descendants of Apao, however, the trigger for a renewed attempt to secure control over the ancestral domain was the setting up of the geothermal power plant by the Philippine National Oil Company.

Drilling began in 1987, but the project gained final approval from then president Fidel Ramos in 1993. The project saw tribal resistance from its earliest inceptions (owing in large part to both the poor inclusion of the Monuvu in consultations and in the nature of Mt. Apo as a biodiversity hotspot). A particularly defining moment of the opposition took place in 1989, when a group of leaders from different tribes performed what they called a Diyandi, a grand ritual declaring war on whoever would harm Mt. Apo.

None of the elders of Apao’s descendants were involved in that ritual, but this was the time they renewed their claim for ancestral domain control. Various groups among the clan emerged to become rival claims: Tuddok ni Ayun Umpan (led by descendants of Ayun Umpan), NABAMAS (Native Barangay Association of Mt. Apo Sandawa, Inc., led by Datu Santiago Aba), TAHAPANTOW (the Association of the People of Tahamaling, Pandanon and Towsuvan/Sitio Waterfall, Bongolanon), and the BADC (the Balabag Ancestral Domain Claim). Some of these groups would later consolidate into two rival claims, the IBASMADC (Ilomavis-Balabag Apo Sandawa Manobo Ancestral Domain Claimants) and the ILAI (Idpossokadoy ta Linubbaran ni Apao, Inc.), which would eventually merge as MADADMA.

(For a detailed discussion of the early development of these movements, Fr. Albert Alejo, SJ’s 1999 dissertation, ‘Generating Energies: Cultural Politics and the Geothermal Project in Mt Apo, Philippines’ makes a useful reference.)

When MADADMA finally secured its Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title, it concluded a decades-long struggle that would also inspire other clans in the area to follow suit. Since then other ancestral domain claims have emerged.

With control over their land secure, the descendants of Apao then proceeded with the struggle for cultural renewal (the subject of Fr. Alejo’s dissertation). The campaign to secure the CADT only succeeded because it took place with a strong cultural component, and the embers of those cultural fires still burn today.

If there is any lesson that can be learned from MADADMA’s experience—and from the experience of Kidapawan’s struggle for ancestral domain control—it is that while setbacks may come and overwhelm us, those fires must never be extinguished. We only really fail when we give up.

(MindaViews is the opinion section of MindaNews. Karlo Antonio G. David has been writing the history of Kidapawan City for the past thirteen years. He has documented seven previously unrecorded civilian massacres, the lives of many local historical figures, and the details of dozens of forgotten historical incidents in Kidapawan. He was invested by the Obo Monuvu of Kidapawan as “Datu Pontivug,” with the Gaa (traditional epithet) of “Piyak nod Pobpohangon nod Kotuwig don od Ukaa” (Hatchling with a large Cockscomb, Already Gifted at Crowing). The Don Carlos Palanca and Nick Joaquin Literary Awardee has seen print in Mindanao, Cebu, Dumaguete, Manila, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Singapore, and Tokyo. His first collection of short stories, “Proclivities: Stories from Kidapawan,” came out in 2022.)

========================================

On this section of Moppiyon Kahi diid Patoy, we remember important dates and incidents that took place in Kidapawan history.

6 June 1952 – The Municipal Hall of Kidapawan was formally turned over to the Municipal Government. It has been in use since.

12 June 1951 – Datu Bulatukan Lambac was appointed Vice Mayor, taking over from Datu Siawan Ingkal, who had resigned to take on an appointment in the province.

12 June 1976 – Kidapawan was made a Roman Catholic prelature, with Frederico Escaler, SJ as first Bishop.

22 June 1963 – The Kidapawan barrios of Magpet, Del Pilar, Inac, Kamada, Tagbac, Kiantog, Kisandal, Kaunod, Illian, Sallab, Kalambugan, Bangkal, Dalag, Lomot, Datu Inkal, Datu Unot, Malibatuan, Datu Selio, Tumanda, Binuangan, Mapayagan, Ulougaga, Midsungan, and Alibayon were separated to form the new Municipality of Magpet, with barrio Magpet being renamed Poblacion and giving its name to the whole town. Part of that territory would separate from Magpet later to form the Municipality of Arakan.

26 June 1952 – Presidential Proclamation 323 of 1952 was signed by Elpidio Quirino, setting aside land for the public domain, which now includes the present location of the market, the Municipio, the city plaza, the public cemetery, the nursery, and Pilot Elementary School. The designated areas were already being used for these purposes by this point.

29 June 1986 – Lumad Mindanaw held its Founding Congress in Kidapawan. This is one of the first pan-tribal organizations in Mindanao, and the meeting one of the first recorded to use the umbrella term “Lumad.”